Iran: Secular Revolt against Clerical Tyranny

The Islamic regime in Iran is occupied with the brutal crackdown of the latest uprising of Iranians, who are fed up with 43 years of repression and are demanding change. The Iranian Revolution of 1979 was a mass popular reaction to the Shah’s dictatorship with hopes for democracy, political freedoms, social justice, and national independence. Though both secular and religious forces participated, in the absence of secular leadership, particularly among the left, many of whom had been eliminated by the Shah’s regime, the religious forces, with the support of liberals, gained the upper hand and claimed it as an “Islamic Revolution.” A good part of the left, infatuated with the populist anti-imperialist rhetoric of the new regime, particularly following the hostage-taking at the US embassy, assisted in their own further demise.

The Islamic regime went through several transformations in the long post-revolutionary period. After eliminating the left and liberal opposition, a clerical oligarchy was established which during the long Iran-Iraq war developed into a clerical/military oligarchy. Post-war reconstruction policies, the hallmark of which were denationalizations and “privatizations” of major industries, mines, and agrobusinesses that were handed over to the cronies and families of those in power, transformed the regime into a clerical/military/business oligarchy. Internal differences among the ruling bloc formed “reformist” and “principlists” factions, and for a few decades Iranians participated in highly restricted “elections,” choosing the lesser of two evils.

The neoliberal policies adopted by successive governments, led to, among other things, the widening gap between the nouveau-riche and the poor majority. Outright corruption, mis-management, and wrong-headed policies created major economic, environmental, social, and cultural crises. Pursuing the dream of its founding father of “exporting the Islamic revolution,” the regime established relations with militant Shia and other Muslims in Lebanon, Gaza, Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, Bahrain, and Yemen, putting itself on a collision course with the United States and its allies, in particular Israel, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. The regime’s controversial nuclear project, further strained its relations with the West and got closer and closer to Russia and China. The confluence of all these crises further deteriorated its relations with a growing majority of the Iranian people, leading to sporadic and intensifying uprisings. As it faced more problems and was losing more legitimacy, it resorted to more repression.

Consecutive and Intensifying Revolts

Throughout these years, and particularly in the past two decades, the Islamic regime has faced consecutive movements and revolts by different sections of the population in reaction to a wide variety of socio-economic and cultural problems. Anger with decades of obscurantism, rampant corruption, incompetence, outright discrimination of all sorts, humiliation, and suppression of dissent created a situation where any spark could inspire a revolt.

The first major revolt occurred in 1999, when university students in different cities rose against the closure of a “reformist” newspaper, demanding freedom of the press. Then in 2009, during the swindled re-election of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, a “principlist” running against an Islamist “reformist” former Prime Minister, a massive protest, identified as the “Green Movement” (nothing to do with environmentalism) brought millions to the streets and attracted the world’s attention. This was mainly a movement of the new middle class with political demands, but did not yet dissociate from religion or the Islamic regime in its totality.

2017 saw yet another major movement and marked an important political shift both in terms of the involvement of the poor as the main participants, and in its political slogans. Disgruntled with the ‘reformists’ ineffectiveness and opportunism, the major slogan of this period was “Principlists/Reformists, this is the end of the game.” The focus was centered on economic issues, inflation, unemployment, and corruption. In 2018 a series of uprisings in different parts of Iran, included in the Bazaar of Tehran, a traditional ally of the clerics. Unstable fiscal and monetary policies of the regime, uncontrolled fluctuations of the exchange rate and the continued decline of the Rial, the national currency, had negatively affected the merchants and traditional middle classes. Other notable events in this period were successive industrial actions, most markedly, in a large “privatized” agrobusiness and in a steel plant in a southwestern province of Khuzestan, where thousands of workers engaged in major demonstrations and work stoppages. In 2019, the government’s decision to sharply increase the price of fuel created a massive uprising that soon engulfed every province and hundreds of cities across Iran. It involved many sections of the population, especially the lower middle class and the working class. The demonstrators openly called for the overthrow of the regime and, for the first time, of the Supreme Leader himself.

In 2020 the environmental catastrophes predominantly resulting from mismanagement of water resources in some cities and rural areas, combined with the recurrent economic issues, created another series of protests against the regime. This period again saw industrial actions and work stoppages in several industries and mines, nurses’ strikes in several cities, as well as protests by groups of people who had lost their savings in the phony Tehran stock market. The assassination of General Qasem Soleimani of the Islamic revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) by the United States, while a major blow to the Islamic regime, created an occasion for it to mobilize public support by orchestrating massive funeral processions. Yet, the shooting down of Ukrainian flight 725 by missiles of the IRGC caused a major uproar and instigated another wave of demonstrations calling for the downfall of the regime. The revolts were somehow delayed by the big toll of the COVID 19 virus on people, which resulted mostly from the Supreme Leader’s ban on the import of vaccines from the West.

Throughout 2021, the regime was faced with other protests in different cities, over a variety of problems. These included: protests against the drying up of a major river in central Iran, the result of the regime’s wrong-headed policies; demonstrations by farmers, supported by city dwellers, in Isfahan; pensioners’ regular picketing in objection to the mismanagement of the nearly bankrupt pension funds; and demonstrations by teachers and contract workers of different industrial projects demonstrating for better pay, among many other examples.

The regime’s reaction to all these social protests and unrest was brutal suppression and killings, detention and torture of the protesters and blaming conspiracies by foreign agents, hence ignoring the buildup of anger and frustrations of a growing number of people of diverse social classes. Meanwhile, with the full support of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, the principlists filled the Islamic parliament and judiciary, various internal factions were silenced, and the hardline principlist Ebrahim Raisi – known as the Ayatollah of Death for his membership in the committee that massacred thousands of political prisoners in 1988 – was mounted as president. The regime felt more confident to follow more radical polices both at home and internationally.

Dissatisfied with the progress in the JCPOA – the nuclear deal with the five permament members of the UN Security Council plus Germany – and angered with the earlier US re-imposition of sanctions and the killing of Khamenei’s most favorite IRGC general, the regime intensified its controversial nuclear and missile programs, and at the same time moved to further push for “Islamization” of Iranian society. The emphasis was placed on the regime’s most representative symbol, the hijab and forced veiling of women. Enchanted with his seemingly absolute power, Khamenei commissioned a propaganda song that came to be known as “Hello Commander” to be sung in all schools, calling for the return of the Mahdi (Shia Messiah) and praising his representative on earth “Sayyid Ali”!

A Different Uprising

The September 2022 death of the young Kurdish woman Mahsa Amini in the custody of the infamous Morality Police was the spark that blew up the tinderbox, and rapidly engulfed the whole country. Compared to previous revolts, the present uprising, with its own unique features, is the most significant, the most widespread, and the most threatening to the Islamists’ power.

As has been rightly noted, it is a feminist uprising. The slogan “zan, zendegi, azadi” (Women, Life, Freedom), that was originally coined by the Kurds, immediately became the main slogan of the whole movement, beautifully portraying the demands of the protestors. Women have suffered more than any other social group under this regime. Forced veiling, the mandatory hijab, has been just one aspect of it, although symbolically the most important one. From its inception, the Islamists in power have considered women as creatures in the service of men and procreation, and for casting votes for the regime’s selected candidates. They changed the Family Law, taking back most of women’s rights, among others, reducing the girls’ age of marriage from 18 to 13, and in many cases in practice to 9 years old.

The present uprising is also clearly a revolt of the youth. Young Iranian girls and boys have been subjected to all sorts of cultural and behavioural restrictions. The Millennials and Generation Z were all born under the Islamic regime and its propaganda system, yet they so valiantly revolt against it. The authorities announced that the average age of those detained in the recent uprising (and we are talking in the thousands) is 15, and among the hundreds who have been killed so far, close to 40 have been children. The same children who were forced to chant “Hello Commander” and hail to “Sayyid Ali,” started chanting the song “Baraye” (“For…”) – put together by a lesser known singer, who depicts all the malaise of Iran under the Mullahs based on the many tweets following the killing of Mahsa Amini. It soon turned into the anthem of the uprising, added to “death to the dictator” and “down with Sayyid-Ali”!

Other than women and girls, university and high school students are the most active elements of the uprisings, with campuses turned into major sites of revolts. Interestingly, aside from important political mottos, like “azadi” (freedom), they call for a “zendegi ma’mouli” (normal life)! Their bravery in confronting the brutal armed uniformed and plain-clothes security agents and thugs, and their innovative guerilla-like tactics of gathering and dispersing in different neighbourhoods, have astonished the whole world.

Another important feature of the present movement is that it has linked the women’s movement to the movements of national minorities, who have also suffered from the very first days of the Islamist regime. Kurdish areas, where Mahsa Amini was from, was the original site of the revolt and continues to be the centre of resistance. The regime, accusing national minorities of separatism, intentionally attacked the Kurdish regions, hoping to provoke an armed reaction. It even bombarded parts of neighbouring Iraqi Kurdistan where many Iranian Kurdish organizations are located. In another region, in Iran’s Baluchistan, the regime gunned down Sunni worshippers coming out of a mosque, killing over 90 people following a mass public protest against the sexual assault of a teenager by a security officer. None of these tricks worked, and the slogans of the protesting crowds keep emphasizing the unity of the Kurds, Azari Turks, Baluchis, and others.

The present movement is strictly secular in nature, is independent of political organizations of the opposition, and has no central leadership. The continued spontaneity and lack of leadership have so far kept it going forward, but to bring its calls for change to fruition, it eventually will need organization and strategy.

Another Iranian Revolution?

The protestors and many others identify the present uprising with another Iranian revolution, and indeed it has the aura of the early phases of the 1979 revolution. However, the 2022 revolutionary actions still lack many of the necessary prerequisites in order to succeed in changing the political system. Without a doubt, the vast majority of the people do not want the current regime. But the regime is still capable of holding on to power. The Islamist oligarchy can still rely on its powerful repressive apparatuses, a double-decker military in the form of the IRGC and the Basij militia, and the regular armed forces and police. It also has strong influence among militant Islamist organizations in the region and can use them – as it did in 2019 in Khuzestan – for suppressing its own people. While its ideological and economic apparatuses have been severely weakened, it still has influence among millions of believers and beneficiaries of multiple religious foundations and institutions. It also has access to the usual rent-a-mob and can organize intimidating demonstrations – as it did on Friday, October 28, after a most suspicious and concocted “terrorist” attack at a religious shrine in the southern city of Shiraz.

Aside from the lack of needed preparedness of revolutionary forces and a strong organized opposition at this stage – as discussed later – the present revolutionary actions need external support. The regime no doubt has further and further isolated itself internationally, except for the opportunistic support of Russia, China, and several militant Islamist groups and organizations in the Middle East. Moreover, fearful of another major turmoil in the Middle East which, among other things, can further disrupt global oil and gas supply, none of the major powers, despite their rhetoric, seeks “regime change” in Iran. The war in Ukraine has been very beneficial to the Iranian regime, although the way it was dragged by the Russian government to support Moscow in the war has created more problems for it. The progressive opposition, based on past experience with imperialist interference, is also correctly very much against any direct foreign intervention.

The Needed Quadripartite Connections

Street demonstrations alone cannot terminate a brutal authoritarian regime. The advancement of the present movement to a revolutionary status needs a quadripartite coordination and alliance among different sites of resistance: in the streets (cities and neighbourhoods), work places (factories, government ministries…), places of learning (universities, schools), and places of business (the bazaar, large and small businesses). Presently, elements of these sites, most notably the street and universities/schools have temporarily coalesced. In several cases, in some cities the contract workers of several industrial projects, and some store owners too went on short-term strikes. But so far, except in Kurdish areas, there has been no consistency among these sporadic actions. The creation of an organized and sustained connection among the four spheres at the national level, most notably between the workplaces and streets, faces serious obstacles.

What broke the back of the Shah’s regime in the 1979 revolution was the workers’ strikes in the oil industry and other major industrial establishments. Aside from the fact that the oil industry is not as significant a source of income for the Islamic regime as it was for the Shah’s regime, organizationally the industry has gone through major transformations. Under the Shah’s regime the gigantic industry was more-or-less a single integrated body. But under the Islamic regime, the upstream and downstream activities have been separated and each further broken down into multiple layers and sub-layers of numerous separate companies, many “privatized,” each with a significant number of temporary and contract employees. Such was the case for gas, petrochemicals, and most other major industries.

During the 1979 revolution, when “strike committees” were formed in the oil and other major industries, they soon came under the influence of the left and turned into Showras (councils). These councils played a vital role in paralyzing the whole industry. Now, with hundreds of scattered smaller units, such coordinated action would be much more difficult. Moreover, the security arrangements in these strategic industries are much more extensive. The largest division within the oil company is herassat (security), with several thousand employees. When after weeks of delays following Mahsa Amini’s death some workers and employees of the oil industry announced a symbolic one-day strike to protest against brutal suppression of demonstrators, the security officers immediately detained several of the organizers and the strike was called off.

The absence of labour unions in Iranian industries is another major difficulty for workplace actions, notably strikes. After suppressing the genuine workers/employees councils of the revolutionary period, the regime created yellow “Islamic Councils” run by their cronies, and even these phony organizations were not allowed in large strategic industries. To be sure, despite the highly segmented industrial working class of Iran, and much tighter security surveillance, we have witnessed many strikes, road blockages, and many other forms of industrial action in the last four decades. But the lack of unions means there are no strike funds that would assure a strike’s sustainability, as workers do not have savings to support their families. During the 1979 revolution, the big merchants of the bazaar who have historically been close allies of the mullahs were providing financial support to some of the oil workers, and to maintain the strikes sacks of money were sent to refineries and other units. Such helping hands no longer exist as most of those merchants are now themselves an integral part of the oligarchy.

The bazaars have also witnessed major transformations in the past four decades. All the big merchants, the traditional commercial bourgeoisie of Iran, have been rewarded for their support of the Ayatollahs by getting big shares in industries, mines, and banks that were confiscated by the new regime. They have formed their own holding companies and trade monopolies and are part of the Iran’s industrial and financial bourgeoisie. As a consequence, only the smaller merchants and the traditional petite-bourgeoisie have remained in the bazaar, and while many of them are still supporters of the regime and follow the religious edicts of their Ayatollahs, the majority of them have suffered economically both because of wrong-headed policies of the government, and the trade monopolies controlled by their more powerful counterparts. Constant internet blackouts by the regime to prevent exchanges among the demonstrators, have created serious economic losses for tens of thousands of small and medium businesses. Several sporadic strikes in the bazaar and store closures in several cities that we have been witnessing in the present uprising relate to these social classes.

Significant sections of workplaces in the Islamic republic also include a wide array of economic institutions under the control of the IRGC, and also the powerful bonyads, the religious foundations which account for over 40 percent the country’s GDP. Hundreds of thousands of employees and workers of these corporations, holdings, and agencies are obviously not expected to provide any support for the uprisings, at least for now. Also, the vast government ministries and agencies, with over 2.3 million employees, have so far remained silent. Nonetheless, if the uprising continues and expands, there is a chance that they would also join the resistance. During the 1979 revolution, all government institutions formed their strike committees that later turned into Showras.

While the connections between the street and workplaces have so far been limited to sporadic actions by contract workers, the strongest connection with the street and the nightly gatherings of people in certain neighbourhoods and apartment blocks has been with universities and schools. In fact, with the shifting status of street demonstrations, except in Kurdish and Baluchi areas, universities and schools have become the major centers of demonstrations. However, despite their amazingly brave resistance in the face of the brute force of the security forces, and the heavy casualties that they are enduring, the schools and university demonstrations and strikes alone will not be sufficient to bring the regime it its knees. Much organizing and strategizing will be essential in order to connect the four spheres of political actions.

Debilitated Iranian Opposition

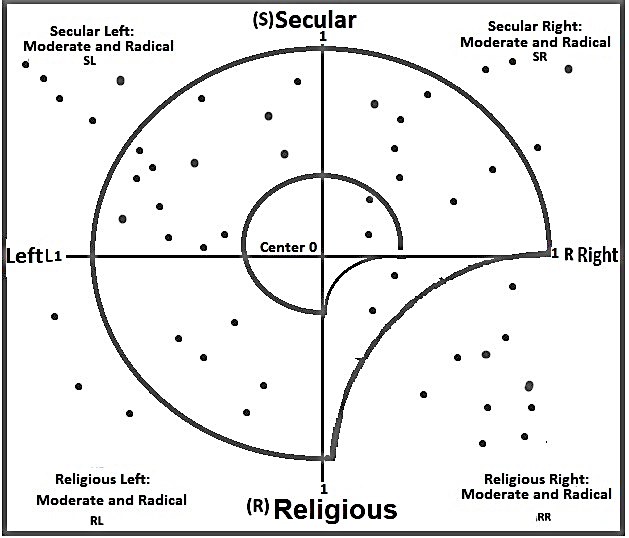

A successful revolution, above all, needs a strong organized opposition, which is currently lacking in Iran. I have portrayed the present Iranian political groups and organizations in a biplot/multi-dimensional matrix (see below): left/right; secular/religious; and radical/moderate, forming four categories of Secular-Right, Secular-Left, Religious-Left, and Religious-Right, depicting scattered political organizations across all these axes. On the far side of the secular-right are the royalists who hope to re-establish a monarchy under the former crown-prince with the help of the United States and its western allies. On the far side of secular-left are a multitude of small socialist and communist organizations, each desiring to immediately move toward a socialist revolution by the working class. On the far side of the religious-left are the Mujahedin Khalgh (MKO), who wish to bring their ‘hidden’ leader to power to establish a different religious state with the help of hardline US Republicans. In the far corner of the religious-right is the regime itself and the multitude of its organizations. Its so-called “reformists” have been so disgraced that it is hard to make any distinctions within the currents of the ruling bloc.

It is obvious that none of these opposition groups at the far corners of the matrix are willing to cooperate with each other, and are actually more busy fighting amongst themselves. In the middle of the matrix, there are a multitude of moderate left, liberal, and religious organizations that call for a secular democratic state replacing the current regime. Despite much infighting among these groups also, there have been some successful efforts for unification or united actions. The main problem for all these moderate and radical opposition groups and organizations is that they are all survivors of the 1979 revolution and are outside Iran, with almost no mass base inside the country.

A major difference between the present uprising and the previous ones is that now a significant and growing number of the Iranian diaspora have come together to support the uprisings. Over six million Iranians who live outside the country migrated or took refuge in the West in the years after the revolution. The overwhelming majority belong to the new middle classes, are highly educated and have found a relatively strong foothold in their respective countries of residence. They have become more and more politically active, but the vast majority do not belong to or support any of the existing opposition groups. The main call to support the uprising in Iran which brought hundreds of thousands of Iranians in over 150 cities in different parts of the world to demonstrate, came from the spokesperson for the families of the downed Ukraine 725 flight. No organization singularly or combined with other opposition groups could mobilize such gatherings, e.g., a hundred thousand in Berlin, fifty thousand in Toronto, among others. The Iranian diaspora has also so far been very successful in attracting the attention of the world to the atrocities of the Islamic regime in Iran. Yet, despite all the potential capabilities, it needs sustained organization, and connection among the diaspora opposition groups and most importantly with the movement inside Iran.

The role of the left is most significant here, because among all existing political organizations it is the only current that defends the rights of the working class and the lower echelons of the new middle class, and its thoughtful and measured presence in the movement can have a positive impact on the mobilizations in workplaces. This is particularly important as the right wing and royalists have gained momentum with the support of influential media outlets outside the country. The problem, however, is that in the wide spectrum of left organizations, we have on one extreme organizations that have openly or tacitly put aside their socialist ideals, and on the other extreme, we have a wide variety of small communist “parties” and radical socialist organizations that repeat the Bolshevik and Maoist perspectives of the past and call for the immediate establishment of the dictatorship of proletariat, without taking into consideration the subjective and objective realities of today’s Iran. There are also left organizations and individuals who adhere to democratic socialism and social democracy. If a major section of the left cannot form a leftist front, it will again be the main loser of the current and the impending political changes in Iran.

The End Game

It is very difficult to anticipate the direction that the present uprising may take, or whether it can succeed in toppling the brutal Islamist regime in power, or if like previous uprisings it will be suppressed until an undetermined time in the future. There are many possible scenarios, depending on how long the present uprisings can last and the nature and extent of the regime’s responses. The regime, as in the end phase of other dictatorial/oligarchic regimes, has reached a point of no return and is faced with a catch-22 situation. If it retreats, the forces of change will make more advances. If it does not retreat, it will be faced with a stronger revolutionary upheaval. The leading figures of the regime have openly said that they will not repeat the mistakes of the Shah and will not retreat, and the improbability of the regime reforming itself is a proven fact.

What is imaginable is that if it cannot suppress or slow down the uprising, it may resort to all sorts of machinations, ranging from a direct takeover of the government by the IRGC to frighten the forces of change, or instigating an attack on a neighbouring country to provoke foreign powers’ involvement and claim a threat to national security. What is most certain is that regardless of what happens, the regime is no longer what it was or could have been prior to the present uprising. Even if the regime succeeds in suppressing the movement, this would only be a Pyrrhic victory, having weakened itself so drastically and discredited itself nationally and internationally. The present movement is definitely the biggest nail in the coffin of the Ayatollahs’ regime. •

This article first published on the New Politics website.