A view from Cuba: Ukraine to the Limit

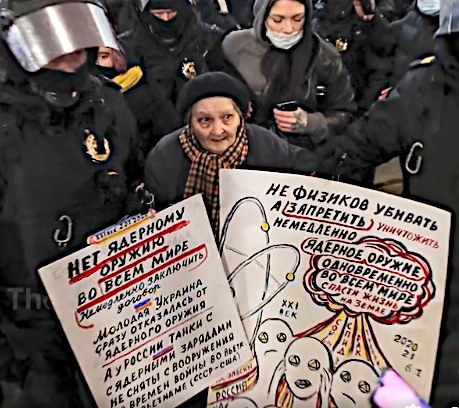

A friend sent me a video of a family in front of a burning building somewhere in Ukraine. We were both shocked. On my Facebook, I share a video of Russian protesters against the war unleashed by their government. Someone comments: “Putin, the new Hitler.”

Ukraine is far away for Cubans. It is difficult to understand the conflict beyond the calls for peace and the repeated slogans. We know something for certain. The invasion violates international law and the right to self-determination. It can only be condemned unconditionally. That said, much remains to be done. First, understand what is being condemned.

The War and its Timeline

The chronology of this war suggests that it did not start [eight] days ago [Feb 24]. However, there are timelines that confuse more than clarify. A common opinion is to place its beginning in the Russian annexation of Crimea (2014), or in that country’s invasion of Georgia (2008). Certainly, there are more complex chronologies to understand the conflict.

First, a long wave can be discerned. In its history, Russia has experienced at least three kinds of imperialism. The imperial idea – tsarist/Stalinist – seems to be embedded in Russian culture.

Ukraine has been seen, from the Russian perspective, as a “little brother,” “a child who must be led by Russia”; as part, without further ado, of Russia. With typical imperial arrogance, Russian President Vladimir Putin has now denied Ukraine’s right to exist as a nation. In this logic, before the invasion, he had already practiced hybrid warfare scenarios against Ukraine.

Expelling hostile borders as far as possible from its territory has been a constant in Russian culture. Ukraine was key to Napoleon’s and Germany’s invasions of Russia. Russia has historical “fears” of threats to its security. It’s not uncommon: it saw nearly 27 million people die in a war that still has survivors.

Second, there is a medium wave timeline. It is the “30-year perspective,” suggested by Rafael Poch, which supposes locating this war in the post-Soviet period and space. Here the role of Europe and NATO in shaping a security scheme under US command is crucial. Large red areas appear in this timeline. After 1991, Russia received a promise that NATO would not move “one centimeter to the east.” So far, it has moved 800 miles in that direction.

In 1995, William J. Burns, the director of the CIA at the time, wrote in a report from Moscow: “Hostility to an early NATO expansion is almost universally felt across the domestic political spectrum here.”

In 2008, a diplomatic adviser to George W. Bush wrote that “Putin would regard moves to bring Ukraine and Georgia closer to NATO as a provocation likely to provoke pre-emptive military action by Russia.”

In that year, Putin stated that “if Ukraine enters NATO it will cease to exist” because it will split. The Russians also offered carrots, the West ignored them. In 2009 Medvedev insisted on an old Russian proposal, advanced ever since the Perestroika era: “draw up a legally binding agreement on European security” that would put an end to the tensions of the time, the same ones that have broken out now.1

It is hard to imagine any Russian president accepting a NATO presence on its border. NATO’s missiles could then hit Moscow in five minutes. Herein lies a tragic irony: no one in Europe thinks about continental security without Russia, but no one seems interested in making it part of the solution. In fact, more than 30 years have passed since the first Russian invitation to an agreement, and all the words in that direction have fallen on deaf ears until today.

#NotoWar, but also No to Atlanticism…

Seen from the “30-year perspective,” the ideology of Atlanticism is a self-fulfilling prophecy: it portends problems that it itself creates while presenting itself as a solution. Other ideas of Europe, such as conceiving it as a space without military blocs, in exchange for a shared scheme of European security, suggested by Mikhail Gorbachev, were rejected in favor of the Atlantic vision.

This happened in the middle of an ocean of lies. One of them is that the enemy had been communism, not Russia. Thus, everything would be fine: another bitter pill swallowed by Gorbachev, and by Putin, for a time. Another was to accept the partition of Yugoslavia, by Germany, against the promises made by the then nascent European Union.

Atlanticism has always sought to keep the United States within Europe. Without the old continent, the idea of world hegemon loses meaning, and much worse, a crucial base for its power. It is an issue with many dimensions: the current Ukraine war will make Germany more dependent on US natural gas.

Portraying Russia as the loser of the Cold War, and pounding away at its image of an extinct power, now drunk and toothless, was a concrete political-military project: after 1991 Zbigniew Brzezinski proposed dismembering Russia into 4 or 5 pieces.

In the process, the military industrial complex made a killing in Europe, arming the new members of the five waves of NATO expansion, and in the wars in the Middle East. From 1991 to now, Kyiv has received at least $4-billion (US) in military assistance, not counting the amounts received from other NATO members.

During this time, the privatization of war also became the norm. In Iraq, mercenaries were already earning a thousand dollars a day. The Azov Battalion, an armed neo-Nazi group formally integrated into the Ukrainian Army, admits mercenaries from twenty countries, including the United States, the United Kingdom and France.

In the process, the Atlantic actors did not show the least concern about redefining borders – when the changes served their interests. Nor was it difficult for private businesses to profit from the conflicts, operating within “Russian” schemes of influence peddling.

Hunter Biden, son of the current president, was a director of the Burisma gas company, the largest in Ukraine, from 2014 to 2019. He would have received up to $50,000 a month. His father is now dealing with this war while the polls predict a probable Democratic defeat in the next midterm elections.

Atlanticism is an ideology of war, profit and possession that sells, under monopoly conditions, exotic products – if we follow John Rawls correctly – such as the “liberal order” and “rule-based systems.” The question “what about the inhabitants of the regions” to which such goods are sold, is not remembered in the Middle East. Nor are shared rules remembered for the Atlantic expansion to the East.

Russia, the Further Away the Better

That question now resonates in the case of Ukraine and its right to choose to join NATO. It is all very well to ask the Ukrainians, but it would be better if it were understood that this question has an inescapable prior basis: the very deep fracture that exists in Ukrainian civil society, which led to nothing less than civil war.

The question would be even better if the Ukrainians were really listened to. Viktor Yanukovych, a pro-Putin satrap, proposed to Germany something quite sensible for many Ukrainians: a three-way European agreement with Russia. German Chancellor Angela Merkel told him that it was only possible if Russia was excluded. As a result, the equally unpresentable oligarch Yanukovych rejected the proposed agreement.

One need not be very bright to understand that a solution for Ukraine without Russia is no solution at all. To begin with, Russian is the native language of most Ukrainians and several of its major regions share Russian ethnicity and culture. The rejection of Merkel’s proposal exploded in Yanukovych’s face.

Starting with the “second” Maidan, which captured the legitimate social protest at the beginning of the revolt, now with support from the West, the anti-Russian zone of Ukrainian politics and culture has enjoyed Western support until today.

Many of those who today rightly oppose the Russian invasion are unaware of these facts: since 2014 there have been 14,000 deaths and hundreds of thousands of refugees and displaced persons. This is the result of the “Anti-terrorist Operation” that the Kyiv government launched. It militarized the civil war against “pro-Russian” actors in the east of the country and spread terror in the conflict regions.

The Minsk Agreements have not been fulfilled. Signed by the main stakeholders, the accords sought to integrate the pro-Russian separatist territories back into Ukraine. The current president, Volodymyr Zelensky, refused to comply with them. He has been the biggest electoral disappointment in the recent history of that country. The disastrous record of his government has led him to increasingly depend on the extreme right, which views the Minsk Agreements as a defeat at the hands of Russia.

President Zelensky could have asked the Ukrainian people to choose between a number of options for their future. Some of these weren’t so dreadful, for example exploring different notions of neutrality, such as those of Finland, Austria or Sweden, open to the West, but without being members of NATO. Instead, Zelensky, outwardly dependent on the West, reformed the neutral status enshrined in the Ukrainian constitution since the 1990s, thereby smoothing the path for the country’s entry into NATO.

An old Atlantic objective appears here in full force: that Russia stays outside Europe. For this, it doesn’t matter what the Ukrainians, diverse as they are, think about Russia. Above all, if they think something different from what the West thinks about Russia.

There are also other truths here, these ones have been heard. The support programs of the IMF and the World Bank – to which Ukraine turned after 2014, leaving a debt of $3-billion to Russia unpaid – have provided for something that has been illegal in Ukraine until now: selling land to foreigners.

With the new agreements, in 2024 it will be possible to sell up to 10,000 hectares per transaction. The area that will qualify for sale is equal to the size of California, or the whole of Italy. It is not just any land: Ukraine has a quarter of the fertile soil of the “black lands” of the planet, it is the world’s largest producer of sunflower oil and the fourth-largest producer of corn.

In other times, the connection between expansion, war and capitalism was called imperialism, but we live in more practical times. All things considered, condemning the war against Ukraine without questioning Atlanticism, which continually generates wars, seems to be the same as trying to cook with an electric pot in the middle of a blackout.

The Ukrainian Nationalist Far-Right and “Denazification”

The transition to capitalism in the post-Soviet space involved an orgy of looting and corruption, politely presented to the world as “privatizations.” Ukraine was an outstanding student in that class.

The process unfolded with alternations between pro-Russian and pro-Western regimes, and with continuities: the oligarchic bureaucratic system of the communist “old regime” was transmuted into an oligarchic, corrupt and mafia capitalist system, which did not guarantee democracy or economic development and that severely curtailed social rights. Today Ukraine is the poorest country in Europe, being the eighth in population.

In the face of the Ukrainian structural social crisis, the nationalist far-right emerged and grew in influence. It functioned as an ideological mechanism of compensation and exchange: in the absence of distributive policies, successive leaders have embraced exclusive and chauvinistic policies of identity.

Nationalism is a resource that is always at hand to heal a nation’s wounds. In its right-wing aspects, it promotes national pride and identification, while wildly misinterpreting the structures for the production of offenses, which it understands are always generated by an outsider. That outsider, since 2014, has been Russia: the universal explanation for all Ukrainian ills.

Ukraine is perhaps the most tolerant country in Europe toward the extreme right. Whereas in other countries they have to run in elections, without explicit permission to engage in violence, in Ukraine they have guaranteed space for street actions, carrying Nazi emblems and promoting fascist speech. The ultra-right benefits from foreign support, including from the United States.

Right-wing nationalism has strong cultural and political roots in Ukraine, which has built part of its identity against Russia. One of its regions, called Galicia, in the Ukrainian area closest to Europe, has been this tendency’s historical grazing ground.

Within it, Stepan Bandera has become a “national hero” after the post-Maidan governments. During the Great Patriotic War, Bandera followers were responsible for killing at least 70,000 Jews between 1941 and 1944, collaborating with the German fascists against the Soviets.

The rightists had an argument that they could use: the Stalinist policy against Ukraine, which starved between 2-4 million Ukrainians to finance Soviet industrialization. The fact, known as Holodomor, has dominated the agenda of current memory policies.

The issue is not just about memory, especially when Zelensky is Jewish. This right-wing nationalist tendency, part of which openly celebrates Nazism – although it is always a Ukrainian-style fascism – has managed to become official policy in several fields: “de-communization,” outlawing the Communist Party of Ukraine and “Ukrainization” (which includes a ban on the use of the Russian language).

This right-wing nationalist tendency has hijacked an old dictum of Ukrainian culture: we are different and we have to manage somehow to live together.

Such a pact had been respected even by the post-Soviet political-mafia schemes in Ukraine, where there are at least two large oligarchic groups, with territorial anchorages, one “pro-Russian” and the other “pro-Western.” Both have been aware that annihilating the other was the beginning of mutual destruction.

Putin has imposed his “denazification” speech over top of this reality. He says that his goal is regine change, removing the “pro-Nazi junta” that now governs Ukraine.

Putin operates based on an “anti-fascist myth,” which takes refuge in the prestige of the Russian victory against fascism, but which owes nothing to the democratic anti-fascist consensus during the war and the post-war periods. Real anti-fascism was an anti-totalitarian discourse. The myth of antifascism is also used against the outsider. Meanwhile, inside, Putin jails those who oppose his “anti-fascist” war.

Putin is also, and in his own way, an anti-communist and right-wing nationalist. He has disowned Lenin, who he sees as the “architect” of the Bolshevik invention that Ukraine had been. Putin’s anti-Leninism, however, is lucid according to his own interests: he understands that he must oppose Lenin’s policies on the self-determination of nations.

“Speaking” against Lenin, Putin is “doing” something else: denying any possibility of federalism, pacifism and respect for plurinationality. Instead, he is “defending” Stalin (without admitting it) by supporting the Russification of Ukraine.

No to the Russian Invasion, and No to Any Other One

Putin is the direct aggressor in this war, even though NATO has sought it out. The invasion is a continuation of the Soviet policy that brought tanks to Hungary, Afghanistan and Czechoslovakia.

Putin is responsible for the dead and displaced caused by the current conflict. Whatever the outcome of the war, Russia will gain something and will lose a lot. Ukraine and the Ukrainians will have lost more. Ending the war as soon as possible is imperative.

Vasili Nebenzi, Russian ambassador to the United Nations Security Council, asserted that “Russia is not attacking the Ukrainian people, but the ruling regime.” It is hard to imagine anything more cynical.

Heard in Cuba, the phrase gives us the shivers. The arguments for the invasion of Ukraine could in turn serve for a hypothetical US invasion of Cuba. Nebenzi’s phrase contains another irony: the US government says the same thing about its economic blockade against Cuba. Ukraine, in the end, is not so far away from us Cubans. •

This article first published in Spanish on Feb. 26 on the OnCubaNews website, an independent news site on Cuban affairs that appears daily in Spanish and English editions. An English translation appeared two days later. What appears here is a revised version of that translation.

Endnotes

- Previous quotes are found here