The Fourth Transformation and the Future of Mexico

In July 2018, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO) won Mexico’s Presidential election in a landslide. Before the formal swearing-in ceremony on December 1, AMLO was already announcing bold, if not always clearly defined, initiatives built around “republican austerity” and “political love.” He never mentioned the word socialism, and as a matter of honesty, it’s probably a good thing. His “Left” proposals included conservative macroeconomic policies largely consistent with previous Partido Acción Nacional (PAN) and Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) administrations, safe spaces for his capitalist friends (and there are many), and lucrative roles for the military.

Meanwhile, his public relations department worked overtime announcing modest populist programs to manage poverty at the margins without altering underlying power dynamics. He packaged his administration as the Fourth Transformation (4-T), with promises to reduce corruption, improve economic fairness, and provide safety and security. The 4-T became AMLO’s bombastic claim to historical significance, following the landmark events of Mexican independence in the early nineteenth century, liberal reform in the 1850s and 60s, and the national revolution in the early twentieth century.

In this essay, we will examine his populism, his sometimes contradictory commitment to austerity, his growing alliance with the military, and his continuation of neoliberal macroeconomic policies under a nationalist guise. Rather than transforming Mexico, AMLO is tidying up his predecessor’s mess, showing himself to be quite adept at managing capitalism for the capitalist class.

Clean Politics?

AMLO was the first presidential candidate since 1988 to win a majority of the vote, rather than the more typical election scenario in recent decades in which Presidents limped into office with a plurality, generally around 40%. His party, Morena, and its allies also took both houses of Congress, marking the first time a single party coalition controlled both executive and legislative branches since the PRI lost the presidency in 2000. AMLO is not known as an inspirational speaker. Rather, his carefully cultivated image as an honest politician of humble means provided the recipe for victory after a series of PRI and PAN administrations widely known for corruption and incompetence.

He quickly took a series of highly publicized actions meant to demonstrate one of his central campaign promises – “There can be no rich government and a poor people.” He converted Los Pinos, the opulent presidential residence since 1934, into a cultural space open to the public. He tried to sell the presidential plane, a $200-million vanity purchase by his predecessor. When the sale entered its third year without a buyer, AMLO tried an auction, also unsuccessful. Currently, the plane sits in mothballs without a buyer in sight, while AMLO uses commercial flights. On the road, he usually drives an older Volkswagen Jetta. A renamed government agency, the Institute for Returning to the People What Was Stolen (really!), auctioned several million dollars of Lamborghinis, Corvettes, and other ostentatious vehicles used by previous administrations or seized from drug dealers. Lopez Obrador also took a 40 percent pay cut, reduced many high-level government salaries, canceled presidential pensions, and abolished the presidential guard, a 2,000-strong elite military force tasked with protecting high-level officials and international guests. In the context of a $350-billion (US) budget, we’re talking pennies, but the publicity helped cement a loyal following.

Shortly after assuming the presidency, AMLO canceled plans to build a new Mexico City airport, though the facility was already 20% completed and 60% under contract. In the face of polls showing strong support for the airport, AMLO organized a popular consulta to decide its future. With the outcome a foregone conclusion, consulta opponents mounted legal challenges, prompting Lopez Obrador to declare the airport a question of national security. A largely friendly Supreme Court supported this unorthodox move, undergirding a presidency characterized by strong-arming political opponents and little patience for dissent. Ultimately, only 1.2% of registered voters participated in the consulta, with polling stations set up mainly in Morena strongholds. The outcome (70% preferred cancelation) allowed the President to kill three birds with one stone: he canceled a project that he characterized during his campaign as rife with corruption and cost overruns, he marked a clear dividing line between his administration and the previous PRI presidency, and he moved the new airport to the Santa Lucia military base (the military would become a key player in the Morena administration).

Morena Populism

AMLO is perhaps best known for his populism. While serving as Mayor of Mexico City from 2000-2005, he previewed what would become a centerpiece of his presidential campaign by providing small monthly payments to seniors. As President, he expanded social programs with direct payments to seniors, students, and the infirm. While families living in poverty appreciated the help, the manner of delivery replicated the same corporativism (aka clientelism) that kept the PRI in power for 70 years.

The PRI organized urban labor, campesinos, and communities into hierarchical structures that filtered government funds through party-affiliated (though superficially independent) organizations at the national, state, and local levels. Most officials took a cut, leaving little by the time it reached the base, but the system proved efficient for winning elections and controlling social unrest. Before elections, officials often collected voting cards in exchange for fertilizer, seeds, direct payments, etc., with the tacit understanding that future aid depended on compliance. When the PAN and Vicente Fox took charge in 2000, the PRI’s corporativist structures found themselves with dramatically reduced funding and less political influence. The PAN had a new idea – send conditional cash transfers through government programs Oportunidades, Prospera or Progesa (depending on the sexenio – each President likes to brand his own programs). Recipients were expected to meet certain health and education standards, including mandatory school attendance for children and regular health and nutrition checkups. Payments were generally made to the female head of households. This largely did away with the corporativist middlemen (though government bureaucrats still had their fingers in the till) and began to establish a direct link between PAN-initiated welfare programs (however underfunded) and individual citizens. This also left citizens without the organizational links to government, even if weak and tentative, that the corporativist system had provided.

AMLO’s direct payments took on a new twist, borrowing from both the PRI and PAN. Shortly after taking office, AMLO launched Servidores de la Nacion (Servants of the Nation). Some 18,000 government functionaries – previous Morena campaign staff now employed by the Secretaria de Bienestar (Secretary of Well-being) – spread out across the country to deliver cash payments directly to the front doors of citizens. Servidores present themselves as representatives of the President, a new take on the PAN’s individualization of government assistance. Initially, they wore badges emblazoned with the President’s name. A ruling by the National Electoral Commission forced them to cover the badges with masking tape, though AMLO is still hiding underneath. The basic structure replicates Morena’s presidential campaign (and the PRI’s corporativist structures). It utilizes the same people: 18,299 base employees with monthly salaries of 10,217 pesos, 266 regional coordinators with salaries of 73,207 pesos, and 32 state Delegates with salaries of 100,000 pesos. Servidores deliver cash or pre-paid cards directly to millions of recipients, including 8 million seniors, a million unemployed youth, and a million students and farmers.

“Some farmers reportedly fell large swaths of native woodlands only to replace them with newly planted trees to qualify for a monthly stipend of $12.”

Anxious to burnish his environmental credentials, AMLO initiated the $1.4-billion (US) Planting Life program, which aims to plant and tend a billion trees, mostly commercial hardwoods, and fruit trees, and eventually employ 1.2 million mainly rural workers. AMLO wants to extend the program to Central America, with financing from the US, as a way to stem undocumented immigration from the South. But the program has come under criticism for replacing diverse native forests with a commercially viable monoculture that will soon be harvested by loggers. Some farmers reportedly fell large swaths of native woodlands only to replace them with newly planted trees to qualify for a monthly stipend of $12.

While millions of poor, and some middle-class, citizens receive direct payments, social projects like daycare are defunded. For decades, the Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS) operated daycare centers for working families employed in the formal sector and registered with IMSS, but spaces were limited. Applicants often waited years for placement. In 2007, President Felipe Calderon began subsidizing private daycare facilities, part of the PAN’s efforts to privatize social services. The poorly regulated industry was rife with corruption. In the most notorious case, a fire killed 49 children in 2009 at a licensed private center in Hermosillo owned by relatives of First Lady Margarita Zavala. AMLO ended subsidy payments to private facilities in February 2019, citing a government census that identified 50,000 “phantom” children out of a sample of 210,000 formal enrollments. He replaced subsidies with direct payments to parents of $40 per month distributed by Servidores and suggested that grandmothers be paid for child care. Rather than expanding the state system, which was generally recognized as providing quality daycare, or regulating the private system, AMLO converted daycare into yet another political program to secure votes. Meanwhile, quality and affordable daycare is harder to find, and not every family can count on a grandmother to watch the kids.

Historically Mexico had a confusing array of healthcare programs that often combined public and private options. Workers with strong unions, like the electrical, train, and oil industries, had their own hospitals and insurance programs. A third of the workforce employed “officially,” in other words, taxpaying members of the formal economy, were covered by government health insurance. The Instituto Mexicano de Seguro Social (IMSS) operated at both state and federal levels. Government employees, including teachers, had their own health care system, the Instituto de Seguridad y Servicios Sociales de los Trabajadores (ISSSTE). The majority of the population didn’t have “official” jobs, meaning they had no access to State-sponsored health care, in fact, no health coverage at all if they couldn’t afford private insurance. In 2003, the PAN initiated Seguro Popular, a program that offered limited coverage for the uninsured. Seguro Popular utilized an unwieldy combination of State-funded medical centers and government payments to private hospitals, resulting in widespread corruption without achieving universal coverage. By 2018, there were still some 20 million Mexicans, almost a fifth of the population, without coverage. Seguro Popular was characterized at the time as a neoliberal reform that attempted to privatize health care while maintaining limited government funding.

In December 2018, AMLO ended Seguro Popular, eventually introducing the newly formed Instituto de Salud para el Bienestar (INSABI) on January 1, 2020, with a mandate to provide publicly funded health care for 70 million Mexicans in the informal sector. With an initial budget of 152.5 billion pesos ($7.6-billion (US)), INSABI is responsible for contracting existing and new health care workers under federal labor agreements, bulk purchases of pharmaceuticals, maintenance of existing health care facilities, and construction of new facilities, particularly in underserved rural areas. One estimate called for a budget five times larger to accomplish INSABI’s goals. By comparison, the US spent $776-billion on Medicare in 2020 for about 63 million enrollees. Admittedly this is a very rough comparison given significant differences in medical costs between the two countries, extensive use of private medical facilities by Medicare, and the advanced age of many Medicare patients. Nevertheless, Medicare spends about 100 times what INSABI budgets to cover approximately the same number of patients, indicating the challenges faced by INSABI or, perhaps more accurately, the quality of care envisioned by the program.

INSABI represents a radical departure from Seguro Popular. Reconstructing an entire national health care system is a huge undertaking, and it’s too soon to tell if AMLO’s best intentions will be realized. Frequent shortages of some pharmaceuticals, particularly cancer meds for children, have been widely reported in the media. Given the scope of change, some hiccups are to be expected. More concerning is the lack of a clear plan for oversight and evaluation. Lopez Obrador expects his populist credentials to justify any action, even in the face of a country with a long history of government corruption and ineptitude. Unfortunately, his administration is populated with political operators from previous administrations, including many former officials from the PRI and PAN.

If AMLO’s reaction to the COVID pandemic is indicative of his attitudes toward medical care, Mexicans have good reason to be concerned. He repeatedly downplayed the pandemic, scoffed at the use of masks, characterized COVID testing as a waste of time and resources, discouraged sick Mexicans from quarantining, and refused to practice social distancing. In January 2022, he was diagnosed for the second time with COVID. Meanwhile, Mexico has one of the highest death rates globally, and hospitals have repeatedly been overwhelmed with COVID cases.

Economic Development

In the decade before AMLO’s presidency, Mexican economic growth averaged just over 2% yearly – certainly nothing to brag about. In 2019 the economy shrank by 0.2%, then plummeted in 2020 by an additional 8.3%, marking the worst decline in at least 60 years. This can hardly be laid at AMLO’s feet. The worldwide COVID crisis combined with Mexico’s declining oil production and prices in 2019 left the country in the midst of a deep recession. The official unemployment rate hovers around 4%, but that number is essentially meaningless. Mexico does not have national unemployment insurance, so to be unemployed often means to starve. Hence, almost everyone finds a way to hustle a few pesos, even if it means washing car windows at busy corners, selling everything from throat lozenges to self-help books on the subway, or begging. Mexico’s major cities, and many mid-sized population centers, are literally filled with millions of people inventing ways to eat every day. In this context, AMLO’s direct payments to the poorest populations are essential for survival.

Given AMLO’s oft-repeated mantra “primero los pobres” (first the poor), his welfare programs are timely and understandable, while also under-funded and politically inspired band-aids covering serious structural problems. Meanwhile, his development policies leave no room for such guarded optimism. AMLO’s three pet mega-projects take center stage: the Maya tourist train in the Yucatan peninsula, the Dos Bocas oil refinery in his home state of Tabasco, and the aforementioned Santa Lucía airport outside Mexico City.

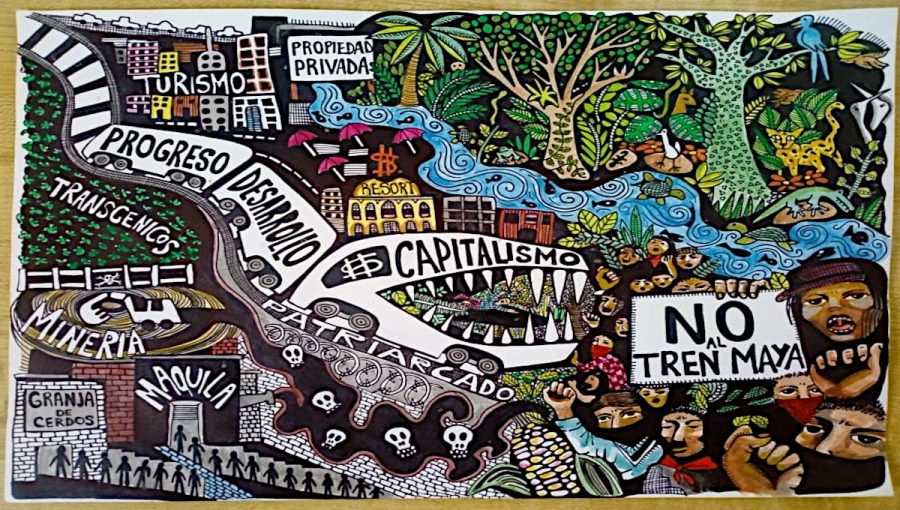

The Maya tourist train is budgeted at $10-billion, but cost overruns are inevitable. AMLO justified the investment with a regional consulta in December 2019, in which 2.4% of eligible voters participated, almost all Morena supporters. Predictably, it was approved by 92% or slightly more than 2% of the directly affected population. In the face of dozens of lawsuits that threatened to halt construction, Lopez Obrador declared the project a “national security” issue in November 2021, thereby sidestepping environmental regulations and civil suits. Upon completion, the armed forces will own the train, with profits going to military pensions. The train is the central piece in a development project for the Southeast that includes natural resource extraction, maquiladoras, tourism, and much more. It is widely recognized as an environmental and social disaster that will displace indigenous communities from their ancestral lands and destroy millions of acres of tropical rainforest. The Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) and the National Indigenous Council (CNI) are among dozens of indigenous, environmental, and civic groups opposing the project.

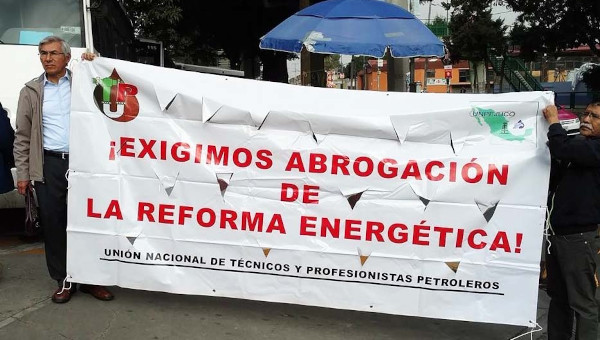

As for the Dos Bocas refinery, AMLO reversed at least three decades of neoliberal energy policies that featured privatization of petroleum and electricity. These policies were not generally popular in Mexico, especially the reforms of 2013-2014 granting foreign oil companies access to Mexico. Under a nationalist and anti-neoliberal banner that combines energy sovereignty and security, AMLO strengthened the two major State energy companies – Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex) and the Federal Electricity Company (CFE). In 2019, Pemex was the most heavily indebted oil company globally, thanks to a combination of corruption and efforts by previous administrations to weaken the company in favor of private energy companies. In 2020, Mexico exported $17.4-billion in crude oil while importing $31.4-billion in mainly processed petroleum products, including gasoline and natural gas (although Mexico has the fifth-largest natural gas reserves in the world). Lopez Obrador wants to make Mexico a producer of finished, high-value-added petroleum products rather than an exporter of raw materials. He faces three major challenges.

First, refinery capacity in Mexico is insufficient and has been decreasing in recent years. The $8-billion Dos Bocas petroleum refinery is intended to reverse this trend. Financed in part by a $600-million Chinese loan, it will be the largest facility of its kind in Mexico, capable of processing 340,000 barrels per day when completed in 2022 – assuming no delays. Pemex will own and manage the facility. AMLO’s national energy plan contemplates updating six existing Pemex facilities, costing between $500-million and $3.5-billion each, for a total capacity of 1.7 million barrels per day. In addition, Pemex purchased the Deer Park refinery from Shell in Houston, Texas. Pemex was previously a 50% partner in the facility. These are ambitious goals, given AMLO’s austerity government without plans to raise new taxes, and it’s not clear if or when financing might be available.

Second, Pemex and the CFE are notoriously corrupt. Pemex’s long and ignoble history includes the Pemexgate scandal in which the PRI transferred $53-million to its 2000 presidential candidate. Pemex employees and union bosses have been implicated in repeated financial chicanery, everything from misuse of company funds to stealing petroleum from pipelines. The recent case of former Pemex chief executive Emilio Lozoya is exemplary, though hardly unique. Lozoya was extradited from Spain to Mexico in July 2020 on charges of bribery, money laundering, and racketeering. Upon his return to Mexico, Lozoya leveled bombshell accusations claiming former Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto, his former treasury minister, two other former presidents, five former senators, and two former presidential candidates orchestrated an extensive corruption scheme, including bribery that facilitated passage of the controversial 2013-2014 energy reform. At first glance, a serious prosecution of Lozoya could place AMLO in the driver’s seat in terms of cleaning up corruption at Pemex. The problem is that many members of AMLO’s administration were members of past administrations and are likely to be implicated in any thorough investigation.

The CFE has also seen its share of corruption. Manuel Bartlett, a prominent member of the PRI before joining AMLO’s administration as head of CFE, was investigated in 2019 for accumulating a $41-million real estate portfolio, impossible on a bureaucrat’s salary. Lopez Obrador publicly expressed support for his embattled employee. AMLO himself is a former member of the PRI and PRD. Long accustomed to the moneyed realpolitik of Mexico, he may see Pemex and the CFE as political cash cows – Pemex alone provides 17.5% of Mexico’s federal revenue. AMLO also covets support from their huge unionized workforces. Only time will tell, but if the snail’s pace prosecution of Lozoya is any indication, AMLO may prefer to manage government corruption for his own political needs rather than reforming the energy behemoths.

Third, in a world threatened by global warming, massive investments in petroleum would appear unwise. In 2020, Mexico had proven petroleum reserves of 8 billion barrels. Given current petroleum consumption, proven reserves could be exhausted in about ten years (though this presupposes no new exploration). Whether petroleum is available or not, many environmentalists would prefer it remains in the ground. After resigning as head of the Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources in 2020, biologist Víctor Manuel Toledo expressed his dismay with the lack of concern for environmental protection. His ministry’s 2020 budget amounted to only 2.5% of the “fossil fuels budget” designated for Pemex, CFE, and the Secretariat of Energy. Toledo is hardly a stellar example of environmentalism – among other things, he was a proponent of the Train Maya. If even someone with Toledo’s political tendencies resigns in protest, AMLO’s environmental policies must be disastrous.

Unfortunately, one of the few “development” options available for most working-class Mexicans is high-risk employment in the narco-political economy. With better pay than government-sponsored development programs, illegal drugs are a lucrative, if dangerous, business that in many ways epitomizes the neoliberal dream of free markets, as well as the neoliberal reality that threatens broad sectors across the Mexican social spectrum. In fact, narco-gangs already occupy important positions in Mexico’s capitalist economy, providing the muscle to control workers on mega-projects, forcing campesinos to abandon strategic properties, and often colluding with the army and police. Narco-dollars are invested in any number of “legitimate” enterprises. Cartels exercise virtual sovereignty in large parts of Mexico, often in concert with the political class, including Morena.

AMLO’s Neoliberalism

Lopez Obrador was a constant critic of neoliberal economic policies, yet most of his program of “republican austerity” is completely consistent with neoliberalism. His commitment to the business community was apparent in the renegotiation of NAFTA, rebranded in 2018 as the USMCA. After tripartite negotiations with the US and Canada, which began in 2017, the text was signed by all three heads of State on November 30, 2018, the day before AMLO’s swearing-in ceremony. AMLO did not participate directly in negotiations, but given his position as President-elect, with outgoing President Enrique Pena Nieto widely unpopular, it’s hard to imagine a scenario in which he didn’t give tacit approval. AMLO publicly and repeatedly criticized the agreement, and he could have torpedoed it by preventing passage of enabling legislation in a Congress controlled by Morena. But he didn’t. AMLO kept his friends in the business community happy while simultaneously maintaining a public populist stance opposed to the USMCA.

NAFTA set the stage for regional neoliberal free trade treaties, and there is little difference between NAFTA and the USMCA aside from the name. The renegotiation was at the behest of Donald Trump, who, more than anything, wanted to distance himself from virtually every political position taken by previous presidents. The renaming achieved that goal at the level of media perception, always the most important level for Trump. Like NAFTA, the USMCA institutionalized the free flow of goods and money across borders while strictly controlling the movement of people. It commits signatories to abide by IMF exchange rate standards and prevents subsidies for state-owned enterprises (it’s not clear how Mexico will square this with increased subsidies to Pemex), both central elements in the neoliberal bible that limits the role of the State in economic affairs. It contains language making it virtually impossible for either Canada or Mexico to sign trade agreements with China, further hitching Mexico’s economic development to US neoliberal capitalism. And it extends some elements of the tripartite open market within North America.

During the daily “mañanera” (in colloquial Spanish, a morning “quickie,” but in AMLO’s lexicon, a daily early morning press conference), Lopez Obrador often berates big business and political elites for fueling corruption and poverty. But behind the scenes, he maintains strong relations with Mexico’s most powerful business elites. Early in his Presidency, Lopez Obrador formed a business advisory council coordinated by Alfonso Romo, at the time the President’s chief of staff (an unpaid volunteer position with no political precedent in Mexico). In his private life, Romo is a billionaire agro-industrialist and owner of the largest fund management company in Latin America. Aligned with the PRI during the Salinas administration (when he accumulated much of his fortune), later with Vicente Fox and the PAN (roughly Mexico’s version of the Republican Party), Romo switched alliances in 2012 and signed up with team AMLO. The council included: Ricardo Salinas Pliego of Grupo Salinas, a conglomerate that includes Banco Azteca, TV Azteca and Elektra; Bernardo Gómez of Televisa; Olegario Vázquez Aldir of Grupo Empresarial Ángeles, a conglomerate that includes Imagen TV, the newspaper Excélsior and Hospitales Ángeles; Carlos Hank González of Grupo Financiero Banorte, tortilla multinational Gruma and Grupo Hermes; Daniel Chávez of Grupo Vidanta, a hotel and resort conglomerate; Miguel Rincón of paper company Bio-Pappel; Sergio Gutiérrez of metal supply company DeAcero; and Miguel Alemán Magnani of Interjet. Note the preponderance of media giants in this list. Televisa is the largest TV station in Mexico, followed by TV Azteca, and Excelsior is a leading national newspaper. AMLO’s efforts to construct a populist image are dependent on favorable media coverage.

Carlos Slim, Mexico’s wealthiest businessman and owner of Grupo Carso, was noticeably absent from the list, though AMLO has a long friendship with the mogul and has met with him privately on numerous occasions. Grupo Carso built much of the elevated train in southern Mexico City that collapsed suddenly last year, killing 26 people, perhaps accounting for some public distancing. Slim and Carlos Salazar, head of the Business Coordinating Council (CCE), Mexico’s leading business association, have influenced key government policies behind the scenes on several occasions. They reversed a threat by AMLO to cancel $12-billion (US) in pipeline construction contracts signed by a combination of foreign companies and Slim’s Grupo Carso. They were instrumental in negotiating an agreement with President Trump to curb a surge in immigration from Central America by using the Mexican military (turning Mexico into the enforcement arm of US immigration policy calls into question AMLO’s nationalist credentials). AMLO even agreed to modify his public discourse by avoiding the use of the word “fifi,” a pejorative term for privileged elites.

Despite his claim as a leftist, Lopez Obrador is often described as a “pragmatist” – read pro-capitalist. He defends his relationships with business elites as necessary for the 4% annual economic growth that he predicts. His “pragmatism” was on display in 2020 when he made his first international trip to Washington, DC, in what can only be described as a campaign stop for Donald Trump. As Politico writes, the two heads of State “built a relationship based on their respect for each other’s nationalist, authoritarian tendencies and their ability to stay out of each other’s way on domestic issues.”

Military Allies

Demilitarization and crime reduction were among AMLO’s central campaign promises. But after three years in office, the military is involved in policing, government management, and the economy in unprecedented ways, while homicide rates are essentially stagnant, with 36,661 murders in 2019 and 36,579 in 2020. Mexico owns one of the highest murder rates in the world at 29 per 100,000 population. According to data from the president’s office, October 2020 saw 214,735 armed forces members carry out public security tasks. 2022 began auspiciously with the murder of two journalists, most likely victims of drug cartels or local officials allied with the cartels. Forty-eight reporters have been slain since December 2018. While most of these cases go unsolved, in cases where suspects are identified, almost half are local officials. Apart from war zones, Mexico is considered one of the most dangerous countries in the world for journalists. The cartels have become so powerful that they’ve literally taken control of some local and regional governments.

In one of his first major acts as President, AMLO launched the Mexican National Guard. The 90,000-strong force is composed mainly of soldiers from the army and navy, with about a quarter coming from the former Federal Police. While formally under civilian control, operational control of the National Guard is in the hands of Luis Rodríguez Bucio, a retired army general, and all of the Guard’s commanders are former members of the armed forces. Most of the Guard’s funding and equipment comes from the armed forces, and all recruitment centers are located on army bases. The National Guard is involved in a wide range of law enforcement activities: immigration enforcement, guarding oil pipelines, investigating common crimes, patrolling the Mexico City metro, and much more. The Guard expands on the military’s already extensive role in fighting (or, more correctly, making alliances with) organized crime and drug cartels. The Guard manages its internal justice system that is not answerable to civilian courts. AMLO’s creation of the National Guard adds to an already aggressive militarization of Mexican society. In addition to public safety and law enforcement, the military controls customs offices at ports, airports, and land crossings; construction of 2700 branch offices of the new Banco de Bienestar, responsible for distributing welfare payments; reforestation programs like Sowing Life; medication and vaccine distribution throughout the country; and textbook distribution across the country, plus 22 military high schools. These are lucrative enterprises, and the military is exempt from civilian judicial oversight.

Mexico’s military has a long and shameful history of corruption and human rights abuses. The case of General Salvador Cienfuegos, head of Mexico’s Ministry of Defense (SEDENA) from 2012-2018, is exemplary. Cienfuegos was critical of AMLO during his presidential campaign, yet when he was arrested on October 15, 2020, at the Los Angeles airport, accused of being a drug cartel boss, AMLO negotiated his release, and charges were dropped. During his time as head of SEDENA, the army was implicated in 3,311 human rights cases presented by the National Human Rights Commission, including the disappearance and presumed murder of 43 students in Ayotzinapa.

During his campaign, Lopez Obrador committed to the gradual return of the military to its barracks, drug legalization, transitional justice, and selective amnesties. He insisted that his policies to combat government corruption and economic inequality would lead to a decrease in crime rates, but since assuming the Presidency, his “abrazos no balazos” (hugs not bullets) means, essentially, the past is past and impunity reigns. Drug cartels continue to exercise virtual sovereignty over large parts of Mexico, while the military and police protect them in exchange for payoffs (see the works of journalists Anabel Hernandez and Jose Reveles for detailed reporting on the links between government officials and narco cartels).

AMLO refers to the military as “the people in uniform.” Maybe he hopes his growing partnership with the military will spawn an efficient organization dedicated to a nationalist project, similar to the Cuban or Venezuelan military. Of course, there are many differences. AMLO has no intention of building socialism, and Mexico’s military, a historically corrupt mess, has little in common with either Cuba or Venezuela. More likely, AMLO is building this relationship, along with his many close working friendships with some of the country’s leading capitalists and media giants, in recognition of Mexico’s existing realpolitik. Behind “abrazos no balazos” and his highly public, though selective, commitment to austerity is a quest for power. Don’t be surprised if AMLO overcomes the constitutional prescription to a one-term presidency or, more likely, rules from the shadows after 2024 by mobilizing his links to the military and the capitalist class.

Where is AMLO Headed?

Mexico’s history is littered with powerful presidential figures. Until the 2000 elections, they chose their own successors in the infamous dedazo (the big finger that figuratively points out the next president). AMLO appears to be moving Mexico back into this PRI-initiated political practice. Everything points to AMLO accumulating power at a personal level which, one supposes, will translate into votes for whatever Morena candidate he chooses in 2024 while he manages from backstage. Lopez Obrador claims leftist credentials, though it’s hard to see on what basis. Karl Marx described his current policies with uncanny precision in the Communist Manifesto. He criticized “reforms … that in no respect affect the relations between capital and labor, but, at best, lessen the cost and simplify the administrative work of bourgeois government.”

Perhaps AMLO’s most lasting legacy will be the weakening, some say dismantling, of Left forces in Mexico. AMLO’s clarion call to poor and working-class Mexicans is backed by real pesos, even if in barely livable quantities. The cost to the federal government is modest, but the social peace it buys in a country slammed by COVID and inequality is invaluable to business elites who are banking on Morena to maintain social stability.

In recent years the Left had a dispersed and inconsistent presence in politics as well as communities. The notable exception is the Zapatistas, whose criticism of Lopez Obrador dates to his days as Mayor of Mexico City and later during his first two presidential runs in 2006 and 2012. AMLO publicly courted the Zapatista throughout his political career, but the Zapatistas have been firm in their rejection, characterizing him as “nothing more than the moderate right.” Their critiques of AMLO cost them some popular support 17 years ago, but now that he’s in power, AMLO has proven the Zapatistas correct. As in the past, his public pronouncements regarding the Zapatistas are generally cordial or non-confrontational, but his actions speak louder than his words. In three years of his administration, Zapatista communities have suffered a series of attacks and murders by paramilitary groups affiliated with Morena or allied parties in Chiapas (see enlacezapatista for extensive reports). Rather than address the violence, Lopez Obrador dismisses it as “indigenous inter-community disputes,” a common racist trope in Mexico’s elite circles, and washes his hands (we will write more about AMLO and the Zapatistas in next month’s news).

After three years in power, AMLO’s shortcomings are now clear. He consorts with the same elites and governs through the same clientelist structures as always. Apart from token redistribution programs, his greatest novelty is expanding the military’s reach across broad sectors of society. Again, the Zapatistas boldly proclaimed his tendencies 17 years ago. Unfortunately, those who dismissed them as “electoral spoilers” in 2006 are not issuing retractions. In fact, some have jumped aboard the AMLO bandwagon, leaving parts of Mexico’s liberal Left disoriented and isolated. The “electoral left” is in fact, the moderate right. While the right is adept at fueling xenophobia, it also stokes powerful social movements and tends to leave state institutions in disarray. This is when the liberal hand of capital steps in, reducing tensions by redistributing a bit more money, charming liberals into accepting extractive megaprojects under the slogan of development, shoring up repressive forces and generally operating in the long term interests of profit accumulation. AMLO has shown himself to be quite skilled at managing capitalism for the capitalists. •

This article first published on the AUSM website.