The Other Pandemic: Violence Against Healthcare Workers

I am old. I’ll be 72 this year. Will I live to 95? If so, what will I be like then? Will I be frail but mentally sound? Or will I be vicious and hostile?

My daughter-in-law, Jennifer, became a nurse just as the pandemic unfolded last year. I was worried about her exposure to COVID-19, but it turned out there were more immediate dangers. Employed in the ICU and ER, Jennifer began with enthusiasm and optimism in her chosen caring profession. But she was attacked by a 95-year-old woman with surprising strength and anger. Looking at the photo of her arm covered in gouge marks and blood, I was appalled. Why would anyone attack this lovely young nurse who is one of the kindest, most empathetic persons I know?

Reading the new book, Code White: Sounding the Alarm on Violence Against Health Care Workers (Between The Lines, 2021), I found out that violence against healthcare workers is not only common, but it has become worse, and increasingly worse beginning in the 1980s, intensifying in the 1990s, and becoming even worse this century.

Researching Healthcare

Researchers Drs. Margaret Keith and James Brophy set out to discover the incidence of violence against healthcare workers and what can be done about it.

Talking with healthcare workers about their experiences individually and in groups gave the researchers unique opportunities to document the incidence of violence in healthcare workplaces, why it happens, and importantly, what can be done about it. This very readable book includes many moving examples of the real-life experiences of healthcare workers being physically and psychologically attacked in their workplaces.

Who are these healthcare workers? In Canada, 85% of healthcare workers are women, and many are racialized, especially among lower-wage healthcare workers such as cleaners and personal support workers. They are more vulnerable than men. The researchers also document assaults on gay male nurses who are attacked because of their sexuality. It is clear the discrimination plays a role in physical and emotional assaults.

The book’s accounts of healthcare workers experiences are shocking:

“On a daily basis, I am hit, punched, spat at, sworn at, slapped, bitten. I’ve had hot coffee thrown at me. I’ve gone home with burns on my hands,” one worker told the authors.

Why on earth is this happening in our hospitals and long-term care facilities? Drs. Keith and Brophy document the causes by listening to and validating what healthcare workers reported to them. Understaffing is a principal cause, leading to delays in care and inadequate care.

Code White asks the question, do you not feel aggrieved when you are kept waiting, even in a bank lineup? Waiting for care in our Canadian emergency departments is even worse, as anxiety about injury or illness compounds the wait. If you are a hospital patient or long-term care resident, would you not begin to feel angry when a seemingly minor problem, easily solved, such as wanting a glass of water or needing to be taken to the bathroom, is ignored? And if this happens time after time to a person who, in addition, is bored, lonely, and may have their mental capacity affected by dementia or drugs, who wouldn’t be frustrated, annoyed, and lash out? And when a family member of a patient or resident sees what they interpret as uncaring neglect, whether in an ER, acute care hospital, or long-term care facility, we shouldn’t be surprised when they shout at or attack the person who they feel ought to be providing this care. But why do these delays in care happen?

Code White provides the answers, using the voices of healthcare workers. Nurses who have been employed a long time in the profession talk about how when they began nursing, they could take time and hold a patient’s hand and comfort them. Today, however, with understaffing, they are rushed off their feet, and the emotional bond with patients has been forfeited. Patients lash out abusively in frustration at being hurried or ignored. While understandable, these abuses should not be part of the job of healthcare workers.

A healthcare worker says:

“The staff are not happy because they are burnt out. It’s not just about protection for yourself. They feel helpless and hopeless because they can’t protect themselves and they can’t protect the residents. I’m supposed to be caring for these elderly people, but there’s not enough staff to. And you take that home with you.”

These grievances are verified by OECD statistical research showing Canada has the longest healthcare wait times among countries in the developed world. The book notes that fifty percent of patients wait more than two hours in the ER, a higher percentage than any other country studied by the Commonwealth Fund. Some governments and administrators blame patients, but the erosion of the family doctor system and short hours for walk-in clinics drive the ill and injured to the ER for necessary treatment.

The book quotes emergency and family physician Dr. Alan Drummond:

“Contrary to the widely held view, crowding in the ER has absolutely nothing to do with inappropriate overuse by patients presenting with non-urgent problems. Rather, it is a function of hospital overcrowding and the inability to transfer admitted patients from the ER to the wards.”

Why has this happened? And what is to be done about it?

Healthcare is Run as a Neoliberal Business Model

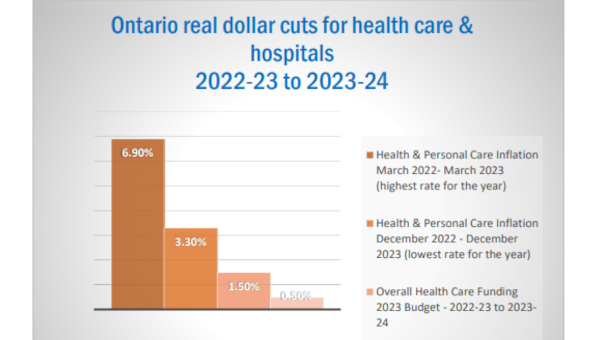

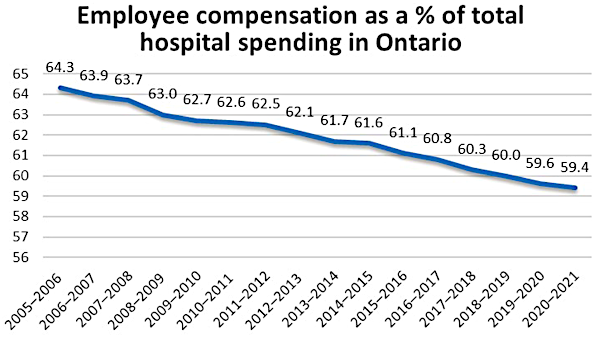

The 1980s brought about the beginning of neoliberalism, privatization, deregulation, and free trade. Throughout the 1990s, hospitals began to operate on a cost-cutting business model rather than seeing patient care as their first priority. Privatization of long-term care facilities began in earnest and intensified. By definition, for-profit institutions are just that: their priority is making money, not providing patient or resident care. The book’s authors argue, and they are supported by many public commissions, reports, and documents, as well as many other researchers quoted in the book, that a privatized business management model is wrong for healthcare.

Code White argues that these models need to change.

Providing better care for patients and protecting healthcare workers from physical and emotional violence go hand in hand. More money for healthcare facilities to hire sufficient staff is critical to ensure patients and healthcare workers are protected and thrive.

The book’s authors argue that change is necessary, and healthcare workers, their unions, and their allies, which should include patients and families, need to fight back, argue for, and achieve positive change in government healthcare funding, policies and priorities, and healthcare administration and management.

As I finished reading the book, I glanced up at the television. The headline on the bottom of the screen said, “Nurses in Kamloops walk off the job claiming they are exhausted and understaffed.” Good for them, I say. Good for them! •