The Historical Backdrop to the Coup in Myanmar

“Oh, the wind, the wind is blowing

Through the graves the wind is blowing

Freedom soon will come

Then we’ll come from the shadows.” — Leonard Cohen, The Partisan.

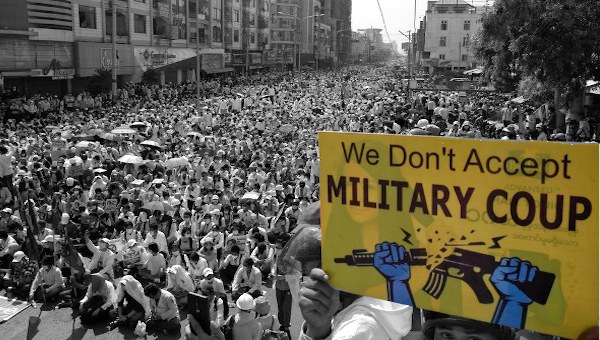

After staging a coup on February 1, 2021, Myanmar’s military – known as the Tatmadaw – has been on a rampage, waging an internal war against its own people. Nearly 1,000 civilians have been killed, and populations in border areas have been bombed. More than 8,000 people have been arrested, including children and family members of agitators the Tatmadaw could not find.

To twist the knife in the wound, the junta has allowed the COVID-19 pandemic to run amok. The healthcare system has fallen to pieces; hospitals are either shut down or stretched to the limit; patients are being forced to treat themselves in their homes; the vaccine rollout has come to a standstill; testing is woefully lacking; the virus has spread into the prison system; and independent health workers are being targeted.

The Tatmadaw has prohibited the selling of oxygen to civilians, permitting private plants to supply only to the state-run and military-owned hospitals. Therefore, anyone who supports the anti-military movement can be easily denied a life-saving oxygen cylinder. Meanwhile, those who have been providing oxygen concentrators for free are being branded as “terrorists.” Pure and naked violence has been the military’s only response to widespread resistance against its long-standing hegemony.

Origins of Military Dominance

Under British rule, Myanmar – at that time Burma – was classified into Ministerial Burma and the Frontier Areas. In the former, the British replaced monarchical governance with bureaucratic administration, angering the Bamar population. In the latter – where the non-Bamar groups lived – indigenous chiefs were retained, and they came to be seen as collaborators with the colonial overlords. In this way, ethnic cleavages were manufactured. These divisions reached a critical point during World War II.

The non-Bamar British Burma Army fought against the Japanese-allied Burma Independence Army (BIA). Then the BIA – the predecessor of the Tatmadaw – changed sides in March 1945, working to drive the Japanese out of Burma. In January 1947, Aung San – General Secretary of Communist Party of Burma (CPB) – and Clement Attlee signed an initial independence agreement.

On July 19, 1947, while negotiations were still being carried out, Aung San and his five colleagues from the interim cabinet were assassinated, at the behest of their political adversary, U Saw. Thus, U Nu became the first Prime Minister of Burma, and General Smith Dun was appointed Army Chief of Staff.

Marginalized by the Attlee agreement, the CPB launched an armed rebellion against the incumbent government, calling for the expropriation of foreign assets and expulsion of landlords. Meanwhile, ethnic tensions increased, owing to the exclusion of many non-Bamar groups from independence negotiations.

Further, the domination by another ethnic group, the Karen, of the top layers of the military and their close links with the British Services Mission irked various nationalist leaders, particularly General Ne Win, who arranged for the discharge of the Karen officer corps. In 1949, the Karen National Union (KNU) initiated an insurgency in opposition to the central government’s indifference to its proposals for regional autonomy and power-sharing.

The Tatmadaw waged a permanent, scorched-earth campaign against the CPB, the KNU, and other rebel groups; villagers in borderland areas were framed as subversives whom soldiers could shoot on sight. The Four Cuts approach – forged in the crucible of this brutality – tried to violently suppress rebels by cutting them off from their sources of food, funds, intelligence and recruits. Borderland populations became a casualty of these counterinsurgency tactics.

Burmese nation-building came to rely ever more heavily on the bloody exclusion of peripheral regions from the collective consciousness. Tatmadaw became an important node of this Bamar-centric narrative, responsible for warding off the disintegration of the Union. The growing heft of the military as a protector of the nation enabled it to wrest political control in 1958, which it maintained for two years.

In 1961, Nu – after winning the 1960 election – attempted to declare Buddhism the state religion. Averse to this move, the Tatmadaw again intervened. Under General Ne Win’s Burma Socialist Programme Party (BSPP), a radical-developmental state was instituted which unleashed policies of nationalization and industrialization.

Driven by the goal of self-sufficiency, dependence on primary commodity exports was rejected, leading to the weakening of Indian and Chinese traders. On the external front, a militantly neutralist foreign policy was adopted; Burma featured prominently in the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM).

The period of 1970s and 80s presented BSPP with growing difficulties. With the slow collapse of the NAM due to the debt crisis and the exhaustion of foreign exchange, state economic enterprises could no longer import the raw materials and machinery they needed. These deteriorating economic conditions generated the 8-8-88 uprising (August 8, 1988), which led to the death of 3,000-10,000 civilians and the resignation of Ne Win.

Reconstituted in the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), the Tatmadaw that came to power under Saw Maung adopted a capitalist path, setting in motion a process that aimed at breaking down the old state-owned economy and moving toward greater marketization. However, dominant sectors remained under the military’s control.

Two military-run conglomerates were established: Myanmar Economic Holdings Limited and Myanmar Economic Corporation. Through these entities, the Tatmadaw controlled everything, from beer and tourism to mining, pharmaceuticals, and gems. At the same time, military-affiliated companies – crony capitalists – reaped huge profits from the privatization of state assets.

Democratic Transition

In 1996-98, after consistent lobbying by human rights groups, the European Union and the US imposed sanctions on General Than Shwe’s regime. Most foreign aid and investment dried up; China – which shares a 1,300-mile border with Myanmar – became the country’s key economic partner. To open the floodgates of Western capital and introduce new opportunities for enrichment, the Tatmadaw devised a roadmap for the establishment of a disciplined democracy.

The military created a new constitution in 2008, held elections in 2010 that brought the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) – the Tatmadaw’s political proxy – to power, released Aung San Suu Kyi – daughter of Aung San – from prison that year, and let her run for elections in 2015. Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NDP) took the reins of power after winning 57% of the vote.

No substantial change occurred. Three key provisions of the constitution guaranteed the army’s continuing sway. First, military control over the three security ministries – Defense, Home Affairs, and Border Affairs – was guaranteed. Second, 25% of parliamentary seats – one in four – were reserved for soldiers handpicked by the commander in chief. Third, all constitutional amendments required support of at least 75% of sitting MPs, which was virtually impossible, given the army’s strategic chunk of assembly seats.

Structural limitations apart, Suu Kyi showed little willingness to challenge the military stranglehold. In fact, she sharpened the edges of Bamar supremacy and cemented the cracks in the structures of economic exploitation. Ethnic armed groups in the border areas were temporarily co-opted through business concessions. These ceasefire agreements with ethnic elites facilitated the extraction and dispossession of land and natural resources in the frontier areas.

Postwar military strategies in the borderlands synchronized with the mobilization of ultranationalist Buddhist groups, contributing to the outbreak of extremist attacks and anti-Muslim sentiments. Hate speech increased, particularly via new social media communities. Sectarian violence and military clearance operations drove hundreds of thousands of Rohingya into neighboring Bangladesh. In 2019, Suu Kyi defended her country’s genocide against the Rohingya people at the International Court of Justice.

Even as ethno-racial practices intensified, neoliberal policies were supported and implemented by the NDP. One-third of the 54 million people in Myanmar’s agricultural sector are landless labourers and 54% own less than 5 acres of land. These precarious conditions were not improved by Suu Kyi’s administration. In fact, rural working people across Myanmar lost access to land and natural resources because of escalating indebtedness, rising costs of cultivation, and enclosures.

They joined the slums and ghettos that now surround metropolitan cities, ultimately finding employment in labour-intensive, low wage jobs. The multiple garments, textile, and footwear factories – concentrated around the port city of Yangon – became sites of ultra-cheap female labour. Even children were not spared this brutality.

In jade mining sites such as Hpakan, children were sent to gather jade despite the danger of mudslides at those sites. An estimated 1.13 million five-to-seventeen year olds remain trapped in child labour in Myanmar; one in every 11 children is deprived of their childhood, health, and education. Nevertheless, NDP continued to enjoy popular support. Lacking strong alternatives, the Bamar majority saw in Suu Kyi the glitter of globalization and prosperity.

The NLD registered a landslide victory in the November 2020 general elections. General Min Aung Hlaing – who had been planning to become president after retirement, in the hope that the public office could shield him from being prosecuted for crimes – understood that the social base of Myanmar’s military was rapidly declining. Hence, he invoked Article 417 of the 2008 constitution, dismissed Suu Kyi, arresting her and other members of NLD. And this has landed Myanmar in its present-day situation. •