Resisting Water Privatization in Europe: Key Reasons for Success

In the wake of the global financial crisis, water services have come under renewed neoliberal assault across Europe. At the same time, the struggle against water privatization has continued to pick up pace; from the re-municipalization of water in Grenoble in 2000, to the United Nations declaration of water as a human right in 2010.

In my new book Fighting for Water: Resisting Privatization in Europe (Zed Books/Bloomsbury, 2021), I dissect the underlying dynamics of the struggle for public water in Europe. From the successful referendum against water privatization in Italy in June 2011, via the European Citizens’ Initiative (ECI) on “Water and Sanitation are a Human Right” in 2012-2013, to the ongoing struggles against water privatization in Greece and water charges in Ireland between 2014 and 2016, the book shows why water has been a fruitful arena for resistance against neoliberal restructuring.

In this essay, I want to highlight the three main reasons for this success: 1) the unique quality of water; 2) the long-standing tradition of water struggles across various geographical scales; and 3) the broad alliances underpinning collective struggles.

Unique Quality of Water

The unique quality of water is perhaps the most important factor of why struggles against water privatization have had such a wide resonance. Water as a source of life, prominent in many religions, resonated deeply, for example, with Catholic Social Doctrine. Unsurprisingly, many Catholic groups played an important role in the struggles over the Italian water referendum in 2011, whether it was in the signature collection demanding a referendum in the first place or whether it was in campaigning for two ‘yes’ votes in the referendum itself. Equally important, my research of the four moments of contestation indicates that water’s unique quality is reflected in the support of public water by many people, who normally vote for centre-right political parties.

Second, the long-standing tradition of struggles against water privatization across different geographical scales was a major factor underlying the successful water struggles. In this book, my focus is on struggles in Europe. However, we need to understand these struggles as nested in wider struggles at the global level. Since the increasing push for the privatization of water services from the early 1990s onward, struggles over water had erupted around the world. Most well-known is the so-called water war of Cochabamba, Bolivia, in 2000, when citizens rose up against privatization and drove the private corporation Aguas del Tunari out of their city. In 2010, the UN declared water to be a human right. These developments facilitated struggles in Europe with the ECI picking up directly the notion of water as a human right for its European-wide mobilization in support of public water. Italian activists, in turn, referred directly to the experience of Cochabamba as a motivation for organizing in their country.

The third key factor for the success of struggles against privatization were the broad alliances underpinning collective struggles. In all the examples of water struggles discussed in this book, trade unions played an important role. In general, trade unions know that privatization often implies downward pressure on wages, working conditions as well as job cuts. Hence, they defended working people in the sphere of production. Nevertheless, they also adopted a broader outlook and appreciated that the workers they organize, their families and wider society also depend on access to clean water in the sphere of social reproduction. Hence, in key moments they have been able to go beyond a narrow workplace focus.

Important Role of Social Movements

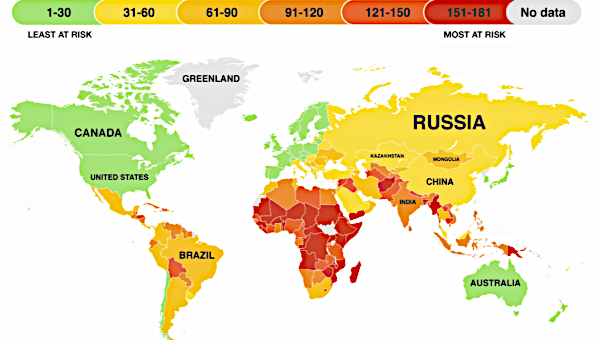

Social movements, citizens’ committees were also active in the various struggles. As water users, they were often the first to be hit by drastic price increases as a result of private involvement in water management. For example, it was local neighbourhood groups, which kick-started the campaign in Ireland through physically blocking the installation of water meters. Furthermore, environmental groups formed a crucial part of the water alliances in Italy, during the ECI at the European and various national levels, as well as within the context of struggles in Thessaloniki, Greece. These environmentalists realised that whenever the profit motive dominates in private water, the protection of water and the environment becomes a secondary issue. Capital’s attempt to secure water as cheap nature inevitably leads to its pollution and undermines water’s longer-term sustainability. The Italian and ECI struggles have also involved development NGOs and their concerns for water access in countries of the Global South.

In short, together the unique quality of water, the experience of water struggles across different geographical levels as well as the broad nature of alliances contesting privatization and the power of capital go a long way in explaining, why these struggles against capitalist exploitation were successful at a moment, when neoliberal restructuring had been reinforced in the wake of the global financial crisis. •