The Modern Tecumseh and the Future of the US Left

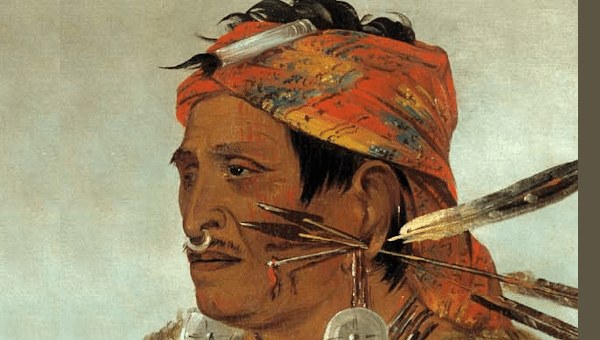

The following essay is not an academic research paper. Neither is it a biography. It draws from the life of Tecumseh and lessons that I believe are useful for the US left. There are many books about Tecumseh, his brother, and their project. One that was especially powerful in triggering my thoughts about Tecumseh’s ongoing relevance is Allan W. Eckert’s A Sorrow in Our Heart: The Life of Tecumseh (New York: Bantam Books, 1993). There are many others, plus information one can obtain at the National Museum of the American Indian and several videos. Tecumseh has a special importance for my family because Fletchers are told, almost from the time of our births, that Tecumseh was an ancestor of ours, an assertion that no one seems to be able to prove but remains a source of family pride. — Bill Fletcher Jr.

Movements are frequently motivated by a compelling story. The story or narrative summarizes the condition of the protagonists and suggests a path forward. In the recent past, however, the left – a term we shall use here to designate political forces that oppose capitalism and the various structural oppressions associated with it from an emancipatory standpoint – has lacked a story. Instead, we have had something akin to vignettes, elements of a story, perhaps better thought of as snapshots. Perhaps it has been the provision of facts and figures concerning what is happening to the oppressed and dispossessed to which we have limited ourselves believing, incorrectly, that the facts alone constitute the story. But it is only when facts, vignettes, etc., are compiled in a logical and compelling fashion that they become a story, and one that can resonate.

Antonio Gramsci, one of the leading Marxist theorists of the twentieth century and a founder of the Communist Party of Italy, understood the importance of the story, or in his case, specifically, the allegory.1 In his Prison Notebooks, he utilized his grasp of Italian history to make a compelling case for the role of organization and strategy in the Italian Revolution that he wished to see unfold.2 The specific and key piece to this story is the now famous reference to “the Modern Prince,” the role that Gramsci saw for the Communist Party in the context of Italy.3

Yet it would be wrong to see in Gramsci’s Modern Prince simply a call for organization or, worse yet, a glamorizing of the Communist Party. Gramsci saw in the work of Niccolò Machiavelli an argument for a specific set of politics that were, in their time, transformative. Machiavelli was an ideologue favoring Italian unification and republicanism. Rather than seeing in Machiavelli simply or mainly a theoretician of tactical manipulation, as became associated with his name, Gramsci saw him as advancing, through his reference to “the Prince,” a specific role for leadership and vision, the sort of leadership and vision necessary to overcome the challenges the Italian peninsula faced in the 1500s.

Modern Challenges

Gramsci’s Modern Prince was faced with an entirely new set of challenges. The left of the first quarter of the twentieth century found itself in an Italy divided north and south in ways that were analogous to the existence of a form of national oppression of the Italian south. The Italian working class and peasantry did not see themselves as having much in common with each other, and it was all too frequent for much of the Italian left to look down its collective nose at the peasantry. Added to this, of course, was that Gramsci composed his famous works in a fascist prison because of the success of Benito Mussolini’s Blackshirt movement (Voluntary Militia for National Security) in subverting Italy’s problematic, constitutionally democratic capitalist system.4

The Modern Prince became a way of expressing the challenges facing the Italian left and a way of situating these challenges within the history of Italy itself. The brilliance of the allegory is not limited to its usefulness in understanding the Italian conjuncture in the early to mid – twentieth century, but it also holds a broader applicability when one considers matters of strategy and organization. This included the role of the party in challenging capitalist rule not solely through a frontal assault, but through what Gramsci analogized as a “war of position,” until the moment arrived for a “war of maneuver.” He focused on the necessity to bridge the north/south divide in Italy as part of building the bloc. Throughout Gramsci’s writings, one gets the sense of trying to better appreciate the history of his own country, that is, not advancing revolutionary theory in the absence of being rooted in a time and place.

This essay is inspired by Gramsci’s thinking on matters of history, strategy, and organization. This essay does not, however, attempt to mirror Gramsci’s works but rather borrows from the spirit of his thinking to grapple with the challenges facing the socialist left in the twenty-first-century United States. Though I believe that some of what I write here has broader applicability, my target audience are leftists within the United States. In part for this reason, I will be using a different historical allegory in order to make a series of points concerning those challenges.

For this writer, Gramsci inspired a journey into the realms of strategy and organization, but the journey does not end there. It does not end with the work of any particular theoreticians. In fact, the journey does not end because at each turn, the left, representing those rooted among the dispossessed and oppressed, discovers new challenges that it must study, analyze, theorize, and, ultimately, act on.

History is not linear. We have a sense as to where the oppressed and dispossessed wish to “land,” but it is the getting there that is largely unpredictable and fraught with immense dangers and the ever-present possibility of failure. Success may be essential, but it is not inevitable.

Tecumseh and the Challenges of His “Moment”

The Shawnee leader Tecumseh (1768–1813) was probably one of the most outstanding and visionary Indigenous leaders in North America.5 Indeed, one can convincingly argue that he was among the most outstanding leaders of any oppressed group in what became the United States. He lived at a pivotal moment not only for Indigenous peoples, but also for the burgeoning country.

The story of Tecumseh, the overall scope of which is beyond what this essay could hope to address, is fascinating. It was, however, in the first decade of the nineteenth century that a different outcome to US history could have been written. I honor Tecumseh and focus on some narrow components of his “story” – especially building a cross-tribal confederacy that can enlighten our work in building a revolutionary strategy and social “bloc.” I consider the allegory of Tecumseh in much the same way that Gramsci thought about “the Prince” – as a means to conceptualize strategy and organization.

Despite the ultimate failure of his military strategy, Tecumseh manifested two approaches that are especially important today. First, Tecumseh embodied “audacity.”6 Audacity involves the imagination to develop a new, concrete, detailed, courageous strategy and organizational approach that has a good chance of success in helping us defeat the right and, ultimately, move beyond capitalism.

Second, like Karl Marx, Frederick Engels, and many others, Tecumseh stood for internationalism. He understood that profound transformation required cooperation and coordination across nations through an “international” organization. For Tecumseh, Indigenous internationalism meant uniting nations that previously focused on tribal organization. For us, internationalism means not only collaboration in progressive and revolutionary struggles across national borders, but also bridging the socially constructed divisions imposed by actually existing capitalism: structural racism, classism, and sexism, in addition of course to tribalism and reactionary nationalism.7

Based most of his life in what we now know as Ohio and Indiana, Tecumseh was preoccupied with the question of what could be done to halt the westward expansion of the white settlers from what had recently (1783) become the United States. There had been various approaches taken by Indigenous peoples in North America toward the European invasion from the very beginning, reflecting, in part, differences in colonial strategy by the various European powers. The French, for instance, who had not placed an emphasis on shifting large numbers of its people to North America, cultivated various alliances with different tribes or nations. Those alliances were not, however, sufficient to defeat the British and their colonist allies in the French and Indian War (1754–63), which was the North American front in what was known internationally as the Seven Years’ War.

In 1763, Pontiac, of the Ottawa Nation, led a confederacy of Native Americans in an uprising that came to be known as Pontiac’s War that, despite some initial successes, ended in defeat. It was in the lead up to the American Revolution/War of Independence that divisions arose between the British and the colonists over expansion policy. The British, in attempting to reach an accord with some Indigenous peoples, sought to stop the westward expansion of the colonists.8 The colonists, many seeking new land for the expansion of farming, did not wish to be held to the territory east of the Appalachian Mountain chain.

Tecumseh observed the approaches taken in response to the westward expansion and recognized that tribal-only engagements as well as traditional confederations would simply not win the day.9 Thus, by the first decade of the nineteenth century, he had concluded that a quite different approach toward the westward expansion/invasion needed to be undertaken.

In attempting to grasp Tecumseh’s approach to the expansion, it is important to factor in the strategic situation, organization, and, to a great extent the most important issue, timing. On each of these Tecumseh was visionary.

The victory of the colonists in the War of Independence created a period of great instability on what was then seen by the colonists as the western frontier. Despite signing the Treaty of Paris in 1783, the British never truly accepted their defeat. They continued to engage in provocations throughout the west (the territory we would now think of as the US Midwest) and cultivated relationships with various Indigenous nations. Yet those relationships were uneven, contradictory, and frequently misleading. The British themselves were far from certain as to how far they wanted to go in provoking the new United States and how trusting they were of their Indigenous allies. They were not beyond implying support when little to no practical assistance was forthcoming, as the one-time allies of the British – the African Americans – frequently discovered.

The former colonies – now states – of the United States were themselves far from unified (despite their name), particularly, though not exclusively, on the matter of slavery. They were, however, united in the need and desire to expand westward, frequently for quite different reasons. While there were periodic alliances between Indigenous nations and the United States, such relationships tended to be short-lived and fraught with regular betrayal by the United States (whether by the federal government or by state authorities). Thus, it was quite clear to Tecumseh and many other Indigenous leaders that there was nothing to be gained by attempting a long-term strategic partnership with the United States.

In addition to the strategic situation, the question of organization plagued the Indigenous nations. The most important matter, and one that frequently affects the oppressed, concerned divisions within the ranks. In the case of Indigenous peoples, tribal contradictions – including but not limited to wars – inhibited ongoing unity of action. Life prior to the arrival of the Europeans had not been paradise. There had been alliances as well as contention between tribes. The arrival of the Europeans exacerbated this situation as the French, Spanish, British, and later the “American” colonists (ultimately the United States) played on those contradictions. Thus, prior to 1763, there had been tribes that tended to work with the French while others with the British. In the aftermath of the War of Independence, the United States continued both the westward expansion as well as the manipulation of one tribe/nation against another. The inability to mount a sustained counteroffensive to the invading United States presented the main organizational challenge within the Indigenous camp.10

Finally, there was the question of timing. For Tecumseh, this had two independent but vitally important meanings. One issue was the actual timing of an appropriate, armed Native American response to western expansion. This involved building the right alliances and mobilizing sufficient forces to present the United States with a crushing defeat.

The second aspect of timing was in some respects quite dramatic; the importance could not be overstated. Specifically, Tecumseh realized in the early nineteenth century that there was a numbers “game” at play in North America. As more Europeans moved to the United States and sought land, there would be an irresistible and, ultimately, irreversible pressure westward that would overtake Indigenous peoples. In this sense, there was not endless time to carry out a strategic counteroffensive and establish a new playing field. Put another way: there was great urgency in terms of addressing the growing crisis. Tecumseh correctly recognized that, short of a dramatic change in the global strategic situation, the window would close on the possibility to defeat the United States if action were not taken soon.

In some respects, the situation confronting Indigenous peoples in North America generally, and that to which Tecumseh addressed himself specifically, was not unlike that confronted by Japan in the lead up to the famous Meiji Restoration (1868–1912).11 Confronted by formidable external pressures and technologically underdevelopment, a revolution took place within Japan, ousting much of the older ruling class and creating a new power bloc that oversaw the development of a modernizing, capitalist Japan. While there were very real internal differences within Japan, civil wars had largely ceased on the consolidation of the Tokugawa Shogunate in the 1600s. This contrasted with the North American Indigenous situation. In both the Indigenous and Japanese cases, timing was everything. Indigenous leaders, including but not limited to Tecumseh, and the leaders within the emerging power bloc in Japan, understood that there was not endless time. For the Japanese, the threat from the United States and Europe was imminent. Had Japan possessed a greater reserve of natural resources, the United States and Europe may have chosen to engage the Japanese militarily without hesitation. In either case, the United States compelling the “opening” of Japan – with a show of naval power – catalyzed the forces that ultimately drove the successful Meiji Restoration as a clear response to the threat from the West.

Tecumseh’s Conclusions

Tecumseh’s conclusions were quite revolutionary. And, while he failed in his task, the approach he sought to undertake held within it the possibility of victory, and victory on a scale that had eluded the Indigenous peoples of North America.12

The Tecumseh construct was straightforward. It began with a recognition that the United States could not be driven out of existence. This was not a battle whereby the United States would cede back all its land to Indigenous nations. The situation was way beyond that possibility by the first decade of the nineteenth century. Instead, there needed to be a fundamentally different relationship between the Indigenous peoples and the United States. This was the key strategic objective.

A second point was a recognition that the forms of organization Indigenous peoples previously employed had failed. Flowing from that recognition there were two conclusions. First, Indigenous peoples needed to reorganize themselves in an unprecedented manner. Second, there was a need for allies to blunt the US expansion.

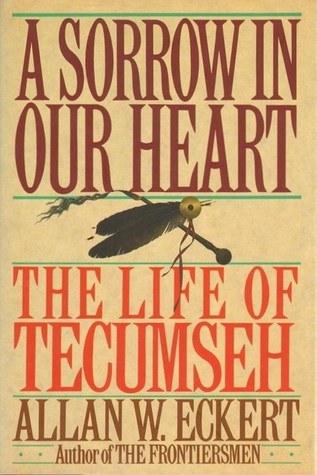

Regarding internal organization, Tecumseh appreciated that no one tribe could defeat the United States and, further, that no loose confederation of tribes would have any greater level of success. Something different was needed. A different form of organization that was linked with a different identity. This is what Tippecanoe/Prophetstown – the centerpiece or capital of the aspiring confederation/nation-state – was attempting to represent, that is, a new Indigenous identity that transcended individual tribes but was a pan-Indigenous identity at the core of a semicontinental alliance or confederation of Indigenous nations. The aim of this effort appears to have been the construction of an Indigenous nation-state that could counter the western expansion of the United States. Tecumseh proceeded to link together the different tribes – and segments of tribes – necessary to put into place this ultimate social formation. Prophetstown was to represent the future, both materially and spiritually.

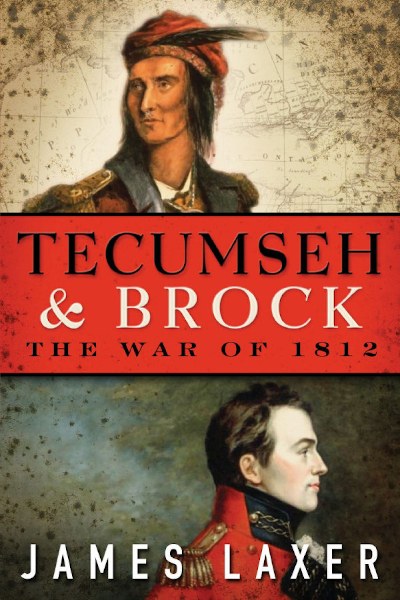

The other strategic and organizational question was that of alliances. There were few apparent cracks within the United States that could be leveraged by the First Nations, but there were obvious tensions between the British and the United States.13 Tecumseh explored and nurtured the possibility of such an alliance. As noted earlier, the British were inconsistent as allies and more than once let their Indigenous allies down. Yet Tecumseh realized that the sorts of material and logistical support needed to confront the United States must come from the British. As time would demonstrate, this alliance was ephemeral. While there were British leaders who appreciated the capacity for such an alliance to reshape the political situation in North America, the racism, opportunism, and condescension of the British establishment limited the actuality of such an alliance, as became clear within the first year of what came to be known as the War of 1812.

Circumstances, of which discussion and analysis are beyond the scope of this essay, resulted in the failure of Tecumseh’s efforts, eventually leading to his death in 1813. Nevertheless, it was the revolutionary character of the strategy and what it proposed that made it worthy of continued study and attention. Poor leadership by his brother at what came to be known as the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811 and the failure of British leadership at key moments in 1813 foreclosed the possibility that a Indigenous confederacy/proto-nation-state under Tecumseh’s leadership could emerge.

The Contemporary US Left and the Tecumseh Challenge

To a great extent, strategy – or perhaps better said, the absence of strategy – haunts the US left. What generally passes for strategy are usually a set of slogans, such as “United Front Against Imperialism” and “Unite the 99%,” rather than anything that approaches a plan. The reasons for this are numerous, but they seem to come down to two principal features: (1) an absence of appreciation of the actual history of the United States and (2) a failure to grapple with the nature of the “moment” or conjuncture in which we live. As a result, the left finds itself responding to events, much like a ship without either radar or a rudder, caught in a storm.

As with Tecumseh, one needs to aim to develop a set of strategic objectives that will guide the actual strategy or plan necessary to succeed. The objectives cannot pop out of the air but must be grounded, as noted above, historically and conjuncturally.

The starting point is to clarify what one means by strategy, when discussed in a left context.

Strategy is, in its fundamentals, a plan for the disposition of forces to achieve an objective or set of objectives within a given period. A strategy, in political or military contexts, assumes an understanding, to borrow from Sun Tzu, of oneself and one’s opponent. But it also necessitates an identification of one’s real and potential allies, as well as real and potential opponents. A strategy must identify, to borrow from V. I. Lenin, the key link in order to undermine an opponent and achieve victory.

It is not possible to speak about a general left strategy, but it is possible to speak of a strategy to which one wishes to win a critical mass of the left to adopt. There is no general left strategy because the left is not monolithic and is far from unified. Given the multiple tendencies, from anarchists to social democrats to democratic socialists to variants of communists, there are not necessarily common assumptions about strategy. Thus, the battle for strategy is the battle to win agreement or a consensus within a critical mass of the left and through which to influence the broader mass movements.

Who Are “We”? Part One

Every progressive movement of resistance (to oppression) or progressive – if not revolutionary – movement for social transformation must establish who, meaning what sectors, are at the core of the movement, and what social movements and social sectors are at varying distances from the core. In this sense, the “we” must be constantly clarified and, in fact, changes in different periods of struggle depending on the nature of the opponent, a point reiterated by Mao Zedong throughout the Chinese Revolution.

Tecumseh understood this and set as his mission the clarification of the “we” in the context of the first decade of the nineteenth century. The “we” were the Indigenous peoples. This was based on a recognition that despite contradictions that had historically existed between various Indigenous nations, the situation facing them represented the principal contradiction between themselves and the invading white settlers from the newly formed United States.

The issue of a principal contradiction is something that has perplexed many leftists and been a source of hostility by many of those who embrace postmodernism. It is sometimes (incorrectly) counterposed to the notion of intersectionality. Yet it is the absence of an understanding of contradictions and particularly the notion of a principal contradiction that renders impossible the construction of a working strategy.

Although the notion of contradiction was not originated by Mao, his famous essay “On Contradiction” both popularized and made more accessible an understanding of contradiction.14 The essence of dialectics involves contradiction, struggle, and the unity of opposites. It is something found in nature and in the world of social movements.

The conception of the principal contradiction suggests that at any one moment there are multiple contradictions in operation within an object, social movement, or social relation. Those contradictions act on each other, but there is always a main contradiction or conflict, not deemed by morality to be “right,” but one whose resolution will affect all others and introduce a new period in the struggle. This is the principal contradiction and over time the principal contradiction can and does change depending on the balance or correlation of forces and the nature of the moment.

Yet history is not linear and is far from lacking in complexity. Thus, contradictions do not operate in isolation. Contradictions, to borrow from French Marxist Louis Althusser, are overdetermined.15 They do not operate in isolation, and they do not act on one another in the absence of other contradictions. Thus, a principal contradiction does not mean the sole contradiction. It also does not mean that a principal contradiction gets resolved, after which one can turn one’s attention to other contradictions in some linear fashion. The principal contradiction is affected by secondary contradictions, not secondary in the sense of unimportant or subordinate, but not representative of the main challenge in that conjuncture.

Much of the discussion about intersectionality is about contradictions, though it is frequently blurred by references to subjective identity rather than a recognition of social movements and societal tensions (and, particularly, class struggle). The discussions can devolve into the relative “importance” of different identities and struggles; or a rejection of alleged hierarchies of oppression, rather than a focus on social clashes.

A Marxist understanding of intersectionality places an emphasis on overdetermination and the intersection of different systems of oppressions and social movements (that oppose them), which, at various moments, result in multilayered social struggles. Whether an individual perceives one’s self to be principally gay or lesbian, Black or mixed, Latinx or Afro-Latinx, is secondary to the manner in which oppressions come together and affect the consciousness and social practice of different groups of people. This is also critically important in understanding that, in every social movement, the multiple contradictions are acting out and cannot be put on “hold” pending the resolution of the principal contradiction. They must be both acknowledged and addressed in the way the principal contradiction is tackled. The failure to do so, as has been seen in myriad social movements, such as anticolonial struggles, ultimately results in major setbacks, indeed retrogression.

For Tecumseh, addressing the principal contradiction – between the Indigenous nations and the United States – necessitated operations on four distinct and interrelated levels: identity, Prophetstown, the grand alliance, and external alliances beyond the First Nations.

Identity involved the specific reconstruction of the understanding as to who “the people” were, in this case, winning myriad Indigenous peoples to see themselves as Indians or Indigenous, and to shift away from their principal identity being that of individual tribes. This was not a moralistic plea but a recognition that they would be crushed in the absence of a collective identity that reflected their challenge vis-à-vis the invaders. It is important to remember that in key moments from 1607 on (the English landing in Jamestown, Virginia), many individual tribal groups believed that they had established a lasting peace with the white settlers even when they could see wars of annihilation being waged against other tribal groups. The consequences were generally catastrophic.

Tippecanoe/Prophetstown was the principal base area for Tecumseh’s project. In the first stories that I heard and read about Prophetstown, it sounded like nothing more than a village. In practical terms, it was a base area and a prototype for the sort of society that Tecumseh and his brother – the Prophet – wished to bring into existence among Indigenous nations. It was a location, geographically and politically, where tribal origin was irrelevant. And it was from Prophetstown that Tecumseh set out on his myriad journeys to secure the allegiance of numerous Indigenous nations to the concept of a grand alliance or confederacy that could possibly have evolved into a nation-state.

The grand alliance or confederacy represented the united front or bloc that Tecumseh saw serving as the foundation for the new Indigenous social formation. In the first decade of the nineteenth century, Tecumseh arranged numerous diplomatic visits to various tribes with the intent of securing their agreement to join the confederacy. Tecumseh achieved major note as a supreme diplomat and was able to convince large numbers of tribes that the new confederacy had a chance of succeeding. The key to this, however, was to avoid premature military engagements with the United States.

External alliances beyond the Indigenous nations represented a final piece of the puzzle and one that proved immensely difficult and unstable. After the US War of Independence, the British were bitter regarding the loss and were itching for a fight. Had the Napoleonic Wars not unfolded, the British would have been well-positioned to have not only been more provocative but might have also chosen to come after the United States sooner than what turned into the War of 1812 – and they might have won. In either case, Tecumseh, exceedingly aware of the contradictions between the British and the United States, played on them through an alliance with the British from whom he sought military materiel and coordination. The front against the US settlers had at its core those grouped around Prophetstown, the larger Indigenous nations confederacy, and what turned out to be an inconsistent, though important, alliance with the British.

A series of unpredictable factors undermined Tecumseh’s efforts in 1811 and, ultimately, led to his death in the Battle of the Thames (in Canada) in 1813. But the framework he offered directly corresponded to the conjuncture or circumstances faced by the Indigenous nations in the early nineteenth century. The defeat of Tecumseh’s effort signaled a greater defeat for the Indigenous nations, who were never again – as a unified people – in a position to reverse or significantly blunt the offensive of the white settlers from the United States.16

Who Are “We”? Part Two

I say: Know the enemy and know yourself; in a hundred battles you will never be in peril.

When you are ignorant of the enemy but know yourself, your chances of winning or losing are equal.

If ignorant both of your enemy and yourself, you are certain in every battle to be in peril.17

As a left, and particularly as the socialist left, who is our constituency? Or, to put it in terms analogous to those of both Tecumseh and Mao, who are “the people”?

The socialist left (and the subset of the communist left) in the United States have largely seen the working class as “the people.” The working class is our base and other sectors are extraneous, a summary of an approach frequently taken. During the Third Period (1928–35) of the Communist International, this approach was framed as a “class-against-class” analysis, that is, the working class against the capitalists.

Over time, a broader sense of “the people” has been tossed around, but one of the difficulties is that it sometimes is done in a way that deemphasizes particular struggles or social movements. This is especially the case with regard to racist and national oppression. Thus, struggles seem to be a laundry list.

There have been some interesting exceptions or attempts at an alternative framing. The 2011 Occupy Wall Street movement ingeniously articulated the “99 percent” against the “1 percent” as a means of giving “the people” a designation with which so many could identify. Though the percentages do not accurately capture the social base within which the so-called 1 percent or the plutocrats operate, it did emphasize the majoritarian nature of the movement that Occupy was attempting to build.18 Certainly, there were limitations, including the tendency to avoid the subdivisions – for lack of a better term – that exist among the so-called 99 percent, such as race, nationality, and gender. That said, it succeeded in becoming a mass identification and one can convincingly argue that it ultimately had an impact on the 2012 presidential elections.

From the standpoint of the socialist left, one must ask: Which segments of society have a revolutionary interest in opposing capitalism? This question is not as easily answered as it may first appear. We are not asking which segments have an interest in profound structural reforms.

What does one mean by a “revolutionary interest”? Simply put, it means that the major challenges this sector faces cannot be successfully resolved within the framework of capitalism. It does not mean, however, that reforms and improvements under capitalism are impossible.

Looking at it in these terms, the workers’ movement, women’s movement, social movements of color, movements under the rubric of gender justice and the environmental movement each represent constituencies whose interests cannot be resolved by capitalism.

As you will notice, this referred to movements as opposed to straight demographics.19 The reason is that within each demographic group there are segments whose interests can be “resolved” within the framework of capitalism. Marx, Engels, and Lenin each recognized that there were segments of the working class that had a material interest in supporting capitalism and imperialism, resulting ultimately in the notion of a labor aristocracy. This term must be understood politically rather than sociologically. Even some workers in the so-called labor aristocracy are exploited and produce surplus value, in the manner that Marx and Engels described theoretically. Yet, that exploitation did not necessarily result in promoting internationalism or a revolutionary spirit on the part of workers in this sector. There were other factors that intervened.

Imperialism and settler colonialism created entire segments of populations that, under other conditions, would have been described as oppressed, but have chosen – politically – to side with the oppressor class and state, and have, in most cases, benefitted as a result.

If one revisits the notion of contradiction, the reality described here fits in. “One divides into two,” as Mao emphasized. In this case, a working class is not ever a monolithic bloc, but rather a social phenomenon wracked with internal contradictions. One such contradiction involves the labor aristocracy as an outpost of the interests of capital within the working class.

Any examination of strategy must recognize the particularities within demographic sectors and social movements. The tendency within much of the left to romanticize different demographic groups or social movements cannot result in a viable strategy because it fails to appreciate the internal contradictions that beset each and the challenges that result.

Tecumseh appears to have had an early recognition of the contradictions between the tribes that had inhibited lasting unity. His fight for unity thus became not only a fight for structure, but also a fight for a revolutionary identity. Revolutionary in this case has two meanings. First, the prosaic meaning of new and different. Second, in opposition to not only a specific oppressor but to an identity imposed on Indigenous peoples by the oppressor.

The iconic South African revolutionary Steven Biko approached a similar problem with his call for “Black consciousness.” As Biko emphasized, Black was not a genetic term, but needed to be understood as the color/un-color of the racially oppressed in South Africa. It was the majoritarian color and did not equate to a particular skin color shade or ethnic group. “Black” was the color of the South African revolution.

Borrowing from Sun Tzu, understanding “yourself” begins with grasping which are the forces that are objectively revolutionary at any point and, therefore, should be central to the definition of “the people” and should be where any revolutionary left bases itself. This does not presume any conscious unity among said forces, but rather the possibility for strategic unity – strategic unity necessitating the direct involvement of an external factor: Prophetstown.

The recognition of the objective revolutionary forces is part one of any equation. The effort to build unity is, as noted with reference to Tecumseh and Biko, one of also putting a name to the unity or reconstruction regarding who “the people” are. It is a matter of building self-awareness.

This question of “the people” may frighten many leftists or may be interpreted in moralistic terms, that is, we are all God’s people, therefore, some conclude, we cannot make distinctions (in other words, we are fighting on behalf of everyone). While there is truth in the idea that the socialist left must always be fighting on behalf of humanity and nature, it does not mean that all humans are necessarily in the camp of “the people.”

Consider the US Civil War. Who, in that case, were “the people”? In mega terms, they were those fighting against the Confederate States of America. This was a contradictory assortment of the population that included African slaves; freed Africans; many white poor in the South who, for various reasons and using different methods, opposed the Confederacy; segments of the Northern white working class and farmers; Northern capital; and those among the Indigenous nations aligned with the North.20

In no way was this a formal alliance. It represented a convergence of interests for a specific period with some elements within this convergence/alliance completely unreliable and certainly inconsistent. Some of the same forces, for instance, that fought valiantly against the Confederacy turned their weapons on the Indigenous nations when the Civil War ended.21 Northern capital had no consistent interest in the democratization of the South, but had an interest in subordinating Southern capital and, therefore, held – temporarily – to an “alliance” with the freed Africans and poor whites who were at the core of Reconstruction. Yet, when satisfied as to the subordination of Southern capital, they and their political representatives abandoned any interest in an alignment with the oppressed.

This alignment had different names. Sometimes known as “the North,” “Radical Republicans,” or the “Unionists.” But they had a designation that differentiated themselves from those who supported or collaborated with the Confederacy (and its progeny).

Particularly in periods of crisis, it is a task of the socialist left to “name the people.” As mentioned, the Occupy movement articulated its “people.” To some extent, the Black Lives Matter movement has named its “people.” The current socialist left, in recognizing the necessary convergence of forces essential for fundamental social transformation, must do likewise.

Tippecanoe/Prophetstown22

Prophetstown was a base area, organizing center, and social experiment wrapped up in one. It was from Prophetstown that Tecumseh embarked on his myriad diplomatic missions to meet with the tribes and the British. It was to Prophetstown that Tecumseh and his core recruited Indigenous people from various tribes. It was his apparent hope that Prophetstown could be a shining example of what the Indigenous nations could create.

But it is the organizing center with which we should concern ourselves. Using Prophetstown as his base, Tecumseh sought to build the grand alliance. This meant that he was keenly aware that no matter how large the Prophetstown settlement became, it would never match the strength and ferocity of the US settler state. The relationship of Prophetstown to the larger Indigenous nations’ confederation needed to be integral rather than marginal, or, for that matter, transactional. Prophetstown, under the leadership of Tecumseh and his brother (Tenskwatawa, the Prophet), needed to lead the confederation, standing in advance of the confederation in what it represented, but not so much ahead so as to lead to isolation.

Prophetstown existed as the “external factor,” not in the sense used to ridicule Lenin’s reference to socialism being brought from without, but in the sense that Lenin and others meant it.23 Prophetstown represented a possibility for the Indigenous nations to conceptualize themselves in a radically different manner. Prophetstown was part of the Indigenous nations’ confederacy, while at the same time remained separate. What was asked of those in Prophetstown was not the same as that which was asked of members of the confederacy, though the leadership of Prophetstown was recognized by the tribes that signed onto the confederacy.

As matters unfolded, the destruction of Prophetstown led to the strategic crushing – though not ultimate death – of the Indigenous nations’ confederacy.24

National Left Political Organization

In A World to Build: New Paths Toward Twenty-First-Century Socialism, the late theorist Marta Harnecker makes a strong and convincing argument for the need for leftist political organization.25 She speaks of a “political instrument,” by which she is speaking of a leftist organization or party. I will not repeat her arguments.

Tecumseh and his work are relevant here. What we can learn from Tecumseh, paralleling Harnecker’s arguments, is the need for a core to move the political project. The political project is much larger than the core and more diffuse. Our political project is ultimately the construction of a bloc (to be discussed later) that advances socialism as an alternative to a patriarchal, racist settler state at the heart of a global capitalist empire.

Prophetstown can be misunderstood as something akin to a utopian commune. It was more of a base area or liberated zone where new practices were introduced in the construction of an Indigenous identity, while at the same time laying the foundation for a major confrontation with the encroaching settler state – the United States. Prophetstown, then, despite the spirituality that surrounded “the Prophet,” was not a home to a closed-off millenarianism awaiting the end of the world. In some respects, one can argue that it existed to prove that it could exist; that another world, in the here and now, was possible.

A national leftist organization cannot be all things to all left wingers. Fundamentally, it must be revolutionary, Marxist, and democratic in its goals as well as practice. Its revolutionary politics need to be not only the politics of social transformation, but the politics of individual transformation. The creation of a new identity that can infuse the popular democratic bloc that needs to be created on the scale of millions of people. It does this in the material (ideological, political, economic) context of imperialism, so it cannot create “socialist relations” through force of will. And it must be a fighting organization – which is part of what a base area does: nurtures the will, ability, and security to fight.

The identity that the national leftist organization seeks for its members is that of comrade, and it seeks to build a counter-state – a “popular democracy” – to the patriarchal, settler capitalist state.

To build and operate as a core, one must review the historical experience of various left projects from the mid–nineteenth century forward. To a great extent, in both the Global North and South, left projects have tended to oscillate between, on the one hand, stage-driven reformism, and, on the other, voluntarism. In both cases, organized left projects have made assumptions about themselves and their own role in the greater process of social transformation. Rather than as a catalyst and educator, even reformist projects have tended to see themselves through a quasi-military lens, for example, as the “general staff.” While such a self-conception makes perfect sense in a military situation (like a civil war), in a non-war situation or in a moment after having won governing power or state power, such a view is laden with landmines.26

The national left organization or party is not the source of all wisdom. A source of education, training, coordination, organizing, and reflection – yes. The national left organization is not infallible. Its leadership of struggles and movements must be won and rewon, as the Communist Party of China demonstrated during their period of renovation in Yenan, and is actualized through self-criticism and rectification.

A national left organization must be rooted within the oppressed and dispossessed, particularly but not exclusively the working class. In the absence of such rooting, a national left organization exists as an advocacy group or support group for the struggles of the oppressed and dispossessed, rather than functioning as an integral component of such struggles. When people have historically utilized the term sectarian, it has meant not simply a factional attitude toward others, but equally an organizational existence lacking a mass base (regardless of intentions).

The project of the national left organization must be something far greater than building itself. This is where the US left frequently stumbles. It tends to think too small about a task that necessitates a level of organization that cannot be counted in the dozens or even hundreds. But it, equally, cannot be a project that is undertaken by a loose assortment of activists.

The organization must be one of “a new type,” but not in the sense that the Joseph Stalin group gave to the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. It must be an organization that has emerged out of and been reshaped by the global crisis of socialism – refounded – yet retaining the revolutionary, Marxist, and democratic character.

The Popular Democratic Bloc

In one sense, Tecumseh, Gramsci, and Mao similarly perceived the need for a broader configuration of forces capable of bringing about revolutionary change. They each had terminology to describe this configuration, and it related, ultimately, to the matter of collective identity.27

For Tecumseh, the Indigenous confederacy may have been a step toward a nation-state. What is clear, however, is that Prophetstown served as a model for what Tecumseh believed to be the necessary configuration and identity of a new Indigenous alignment.

Gramsci emphasized the need for a “national-popular bloc” as the necessary element in the transformation of Italy, with the Modern Prince playing a key role in materializing this bloc. The national-popular bloc refers to a strategic configuration of the key essential forces for whom there is an interest in revolutionary transformation. Noteworthy here is that Gramsci did not restrict the process of social transformation to the working class alone. Though the working class would be essential, Gramsci recognized the need for the Italian peasantry and, quite explicitly, the bridging of the north/south divide in Italy.

Throughout the entire pre-1949 period, Mao constantly referenced “the people” and the need to build united fronts. The most well-known, perhaps, was the anti-Japanese united front initiated after Japanese imperialism began to eat away at China (1931–45). But after the Second World War defeat of the Japanese, there was a need for a reconfigured united front. Mao’s formulation of a “people’s democratic dictatorship” was an elaboration on the multiclass, multisector political alignment (led by the working class) necessary for a liberated China and, as such, a redefinition of “the people.”

The historical challenge for the left in the United States is the conducting of a revolutionary struggle in the context of a racial settler state, one which became a subcontinental geographic empire and, eventually, the hub of a global empire. The construction of the United States as a settler state involved the near extermination of the Indigenous nations; enslavement of Africans; the seizure of northern Mexico; the seizure of territories formerly controlled by Spain, such as Puerto Rico, Philippines, Guam; the racialization of certain immigrant populations from what we now know as the Global South; and the imposition of racist and national oppression successfully implemented through a system of white privilege.28

Tsarist Russia was once described as a “prison house of nations,” a term that overlaps with the experience of the construction of the United States but is far from identical. In the case of Russia, the various oppressed nations were largely confined to their historical territories, like Ukraine and Turkestan, rather than a population mix over the entire Russian (soon to be Soviet) land mass. Nevertheless, in this context, Lenin, among others, appreciated that a new political configuration would be necessary to frame a new identity for those prepared to travel the socialist road. The notion of a Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, regardless of how uneven and problematic, suggested a novel relationship among the peoples of the former Russian Empire, including, in certain limited cases, the actual right to national self-determination along with the elimination of what he termed “national privilege.”29

The social transformation of the United States, while certainly necessitating the vigorous prosecution of reform struggle, will demand both a reconfiguration of the United States itself, as well as the construction of a strategic bloc invested in social transformation.30 For the purposes of this essay, I refer to this as the popular democratic bloc, not a term I originated but one that accurately describes the alignment.

Tecumseh appreciated that the multiple tribes willing to sign onto his proposed confederacy had various – and often times contradictory – demands and objectives. They also had histories of lengthy hostility with other tribes/nations. The confederacy was a means and instrument toward addressing those contradictions as well as focusing the collective fury of the Indigenous nations on the encroaching settler state.

The popular democratic bloc to be constructed needs an identity, and it is the role of the national left organization to help construct that identity as a way of making the bloc self-aware. Ironically, by the estimates of noted right-wing commentator Bill O’Reilly several years ago, approximately three in ten people in the United States were open to an alternative to capitalism. Factoring out people under the age of 18, one may be discussing more than seventy million people. The problem is that most forces on the US left do not think in those terms, but the reality is that seventy million is the initial pool for the building of a historic bloc.

Though the popular democratic bloc must think in majoritarian terms, it cannot assume that it is the majority. Put another way, the popular democratic bloc is a critical mass of the population that ultimately moves in favor of social transformation. It must win over or significantly influence more center and middle forces to defeat the right. But waiting for any majority to materialize in opinion polls will be an eternal challenge. In the US War of Independence, for instance, the colonial population – contrary to myth – broke down roughly one-third in favor of independence, one-third opposed, and one-third in the middle. Thus, the key task ended up being the influencing of the middle through the construction of a strong and energized pro-independence constituency.

Contemporary leftist politics necessitates a similar outlook. The securing of a popular democratic bloc, however, is not a numerical or even demographic task – in the main – but rather a coalescing of social movements that see in the materialization of the popular democratic bloc the means to achieve success for their respective social movements. Additionally, the bloc must have the “face” and “spirit” of these social movements at its core, rather than treating these social movements as guests on a high-speed train over which they have no control.

The popular democratic bloc begins to materialize in the context of actual struggles and a growing awareness of the mutual necessity of various social movements. This is not something that one can expect will happen on its own. This cannot be overemphasized. The sense that many people on the US left have of the 1930s as a relatively progressive decade was not, mainly, about the reforms introduced, but rather about the social movements that converged and saw a level of commonality in their struggles, thus forcing elements of the ruling class to undertake reforms. It is the task of the national left organization to help unite the struggles and social movements through a combination of education, coordination, and joint action. Expecting that the popular democratic bloc will emerge on its own, become self-aware, and achieve strategic direction is delusional. There is no historic basis for believing such a thing can or will happen. One can see examples of this challenge in the Black Lives Matter movement, which reemerged in the aftermath of the murder of Minnesota resident George Floyd by the police. The protests and rebellions proved to be multiracial and global, but they also inspired other racialized populations in the United States to articulate their own struggles against racism, national oppression, and repression. The Black Lives Matter struggle became not only a struggle of US African Americans, but also a catalyst for a broader movement.31 What has been missing are organizational forms that materialize this broader unity, and organizational forms that practice a type of revolutionary, emancipatory politics that helps bring such a unity into existence.

It then becomes the task of the “Modern Tecumseh” – the national left organization – to lead in the building of this popular democratic bloc. To borrow from Gramsci’s commentary on Machiavelli, the Modern Tecumseh is not and cannot be a person. It must be an organization that is driven by the recognition that winning – defeating capitalism and all forms of oppression – necessitates the building of the popular democratic bloc. Thus, diplomacy, education, coordination, joint action, and so on, initiated or joined by the national left organization with the purpose of creating a self-aware and massive force that advances the process of social transformation, are key.

“External” Alliances

There are two points within a discussion of “external” alliances, one flowing directly from the challenges faced by Tecumseh.

First, as with Tecumseh’s burgeoning confederacy, the popular democratic bloc would be, almost by definition, uneven, if not fragile. Realistically, it will not necessarily have a coherent organizational form, but more likely an assortment of organizations with a shared agenda, some of which may join together at moments. Much of Tecumseh’s diplomatic work in the years leading up to 1811 was focused not only on securing unity within the developing confederacy but in holding it together. Such efforts must be central to the work of the Modern Tecumseh.

Second, at the same time, there is the question of external (potential) allies. These fit into two categories: external to the popular democratic bloc and external to the United States.

In Tecumseh’s time, there were Indigenous nations that chose not to join his growing confederacy. What they would ultimately have done had events unfolded as Tecumseh had hoped is anyone’s guess. Within the US social formation, the only possible ally would have been African slaves, though coordinating Indigenous nations’ offensive along with the African slaves would have been extremely complicated. The abolitionist movement would, as it developed, increasingly address the question of the Indigenous, however, in the first decade of the nineteenth century there were no significant white allies of the cause of the Indigenous nations (among the so-called American settlers), and the opposition to westward expansion that did exist was based less on a recognition of the sovereignty of the Indigenous nations and more in opposition to the spread of slavery.

External to the United States, however, there was the British Empire. Though far from paragons of virtue, the British, since 1763, and particularly after the defeat of Pontiac’s uprising, evidenced a willingness to arrive at some accommodation with the Indigenous nations. The reasons were straightforward. Having come off the Seven Years’ War with France, the British could ill afford organized, ongoing hostilities with the Indigenous peoples.

Tecumseh needed weapons and logistical support. He could only reasonably expect to get them from the British. To convince the British that the investment – and risk – was worth taking, the confederacy needed to materialize. For the confederacy to materialize, the various Indigenous nations needed to be convinced of the possibility of victory.

The Battle of Tippecanoe was a major blow to Tecumseh’s efforts. He had instructed his brother not to engage in a battle with the “Americans,” and instead, much like Mao would advocate a little over one hundred years later, to withdraw were the enemy to attack. Timing was everything. Tecumseh’s brother disobeyed, leading to a major fraying in the developing confederacy.

But 1812 provided one more major opportunity and Tecumseh, along with those who remained with his confederacy (reportedly a still significant number of tribal groups), aligned with the British when the War of 1812 unfolded. The initial British efforts provided optimism because of a willingness to coordinate with the Indigenous nations. But this willingness unraveled. The British, who could have combined an alliance with the Indigenous nations with inciting African slaves to rise, might very well have swamped the United States, despite fighting a major war with Napoleonic France in Europe.

For leftists in the United States, these two aspects of “external” alliances are of critical importance. The popular democratic bloc, at its core, will be those who have embraced the need for fundamental social transformation, what I will call the Red/Green Reconstruction. Yet, there will be millions of others who are not necessarily going to be willing to take the plunge toward socialism but cannot be treated as enemies. This may include large numbers of small business owners and, quite conceivably, small capitalists. These forces may be affected by and drawn to the popular democratic bloc due to fear of growing neoliberal and right-wing extremist authoritarianism, as well as fear of the escalating environmental catastrophe. This will be a segment of the population that will, paradoxically, also be in fear of disorder and may look for any number of reasons to embrace the alleged stability offered by the political right.

The other aspects of “external” speaks to the need for the national left organization, and the popular democratic bloc, to be truly internationalist. The revolutionary process in the United States will be one that is fought out globally and not just within the confines of the United States. This is the case because of the role of the United States as the gendarmes for global capitalism and the central role that the United States plays in imperialism and the global capitalist economy.

For much of the US left, internationalism is viewed more as a pleasantry than a necessity. On one level, that is easy to understand, considering the United States stands at the heart of a global capitalist empire. But of course, this does not make it excusable.

External allies for the US struggle, contrary to the situation that faced Tecumseh, do not consist of a force or nation-state(s) that will provide technical assistance. There is no socialist republic sitting somewhere that can or will do such a thing. What does exist, however, are struggles around the globe that target global capitalism, tyranny, and the interference of the United States in the internal affairs of various countries.

The global aspect to the struggle against US capitalism is what makes the necessity for global cooperation more urgent. Since the 1860s there have been various global efforts at cooperation among a wide array of forces on the left. These have included the so-called First, Second, and Third Internationals; the factional Fourth Internationals; the various Pan-African Congresses, “African World” conferences, and myriad other international and transnational collaborative efforts. Each has brought with it promises and problems, the details of which cannot be summarized here.

It is with the postcolonial era and the rise of neoliberal globalization that international solidarity has acquired more immediacy. Efforts at national sovereignty are constantly undermined by global capital and even efforts at progressive change within nation-states are frustrated by domestic and global capital, once again pointing to the need for greater and more genuine solidarity.32

The World Social Forum, an effort beginning in the 1990s that aimed to bring progressive and antiimperialist forces together, was a source of renewed energy, but its refusal or inability to move beyond providing a big “tent” for various movements and projects displayed its limitations.33

Tecumseh appreciated that the struggle of the Indigenous nations was not taking place in a vacuum. He also appreciated that the global context could possibly help affect the outcome of the struggle faced by the Indigenous nations. In the twenty-first century, we must have a similar awareness.

Timing

There is a remarkable fact that one can uncover in even a brief review of history. There are strategically significant moments that occur, each lasting for an indefinite period, but, when they end, do not reopen. These are moments when any number of things appear to be possible and/or when acting or failing to act will have consequences that may last an eternity.

There are countless examples. The Second Punic War (218–201 BCE), with the defeat of Carthage by Rome, completely shifted the balance of power in the Mediterranean but many historians believe that it was Hannibal’s failure to directly attack Rome that offered the Roman forces an opportunity to reorganize and ultimately turn the tide.

For Tecumseh, as noted earlier, the clock was ticking in terms of the ability of the Indigenous nations to frustrate US expansion. The US military was far from invincible, but it was the larger white population numbers that were the long-term threat.34 A full-scale response to the threat from the United States would need to be timed such that it took the United States by surprise and strategically blunted their advance.

Strategic moments are not magical. Many on the left are familiar with the famous statement by Lenin regarding revolutionary situations (a specific form of a strategic moment), paraphrased here as including certain characteristics: when the ruling class is divided and cannot rule in the old way; when the suffering and want of the oppressed classes has become acute; and when the activity of the oppressed has taken a different stage whereby their level of activism has increased qualitatively. A strategic moment would speak more broadly to the convergence of contradictions overdetermining a situation. In other words, not a crisis in general, but a specific conjuncture, much as was seen in the 1918–19 period (in many parts of the planet), or, for that matter, what unfolded in 2020 with the combination of the COVID-19 pandemic, economic collapse, environmental crisis, lynchings and resistance, and the virulence of right-wing populism.

Thinking in terms of “strategic moments” helps one understand that there is no inevitability to progressive, revolutionary change. There are conditions under which dramatic changes can take place, including but not limited to revolutionary situations. And those moments can be quickly lost.

The first two decades of the nineteenth century were such a strategic moment for the Indigenous nations. The balance of forces was unstable. The global situation was equally unstable. US hegemony over North America was far from certain.

In a strategic sense, Tecumseh had to grapple with urgency without running the risk of impatience, a fact that apparently put him and his brother at odds. The nature of the strategic moment necessitated urgency but what it would never forgive was adventurism.

In the context of the United States, the urgency of the moment can be understood by the fusing of the economic and environmental crises and the resulting crisis of state legitimacy within capitalism. This fusing has resulted in great instability, including but not limited to the constant threat (and reality) of pandemics; the various consequences of environment catastrophe; massive population migrations; and the rise of various social movements, some of which are thoroughly reactionary, such as right-wing populism and neofascism.

Global capitalism is seeking a means out of the crises of overproduction and overaccumulation. Neoliberalism may have reached its end but what will replace it, within the context of capitalism, is unknown. In either case, the result need not be anything that approximates democratic capitalism. Various forms of authoritarianism, including but not limited to fascism, as well as a dramatic societal breakdown resulting in warlord capitalism (what some people incorrectly describe as neofeudalism) could be in store.35 It is also possible that there will be some form of reform capitalism, a twenty-first-century version of the New Deal (particularly a Green New Deal). For a Franklin D. Roosevelt-type New Deal to reemerge, a power relationship between capital and the oppressed classes would need to shift on a dramatic scale.

Thus, even at the level of the reform struggle, taking advantage of the strategic moment is essential. The divisions within the power bloc dominating US capitalist society create the possibility for significant reforms, such as a Green New Deal. Yet one should be aware that winning a Green New Deal, while an advance over the current situation, cannot approach success without not only a shift in the correlation of domestic forces, but also a transnational approach to the problems of the economy and environment. In the domestic context, this could be understood as the struggle for the “Third Reconstruction.”36

Returning to Matters of Strategy

The principal contradiction we face in the United States is between the forces of the “New Confederacy” and the forces of democracy. To be clear, the forces of the oppressed have two main enemies: neoliberal authoritarianism and the New Confederacy. The New Confederacy or Neo-Confederacy refers to an alliance between ultraconservative corporate capitalists and a right-wing populist mass movement (a core of neofascists can be found within the latter). Their efforts include rolling back the victories of the twentieth century and establishing a twenty-first century version of the Confederate States of America or a neo-apartheid scenario. Neoliberal authoritarians seek a preemptive strike against the popular movements that they anticipate will grow in strength in response to the crisis of converging economic and environmental catastrophe. The neo-Confederate wing of capital represents the most immediate threat.37

Framing the principal contradiction in this way indicates that, regardless of the powerful rhetoric about “socialism versus barbarism,” in the United States we are not at the point of an immediate fight for socialism. This is largely due to a combination of a fragmented working class (and popular movements), a weak and divided left (operating within the context of the continuing crisis of socialism), and the horrific threat of right-wing authoritarianism that, though a global phenomenon, in the case of the United States is the result of the defeat of key social movements in the early-to-mid 1970s, and a counterrevolutionary thrust of racist and patriarchal forces aligned with key segments of capital.

It is important to remember that the principal contradiction does not mean the only contradiction. It reflects the strategic contradiction that will most influence all other contradictions at a specific conjuncture. As noted earlier, it acts on and is always acted on by other contradictions. There is, therefore, no linear resolution to a principal contradiction.

A second feature of our situation is that the left generally, and the socialist left in particular, is on the strategic defensive. Drawing from Mao, this means that our opponents – capital and their political forces – have been on the move against the popular movements and the reform victories of the twentieth century since the 1970s. The political right has been eating away at the various gains that popular movements have won. In response, the victories that the “people” have won in the last forty years have been largely tactical and sometimes primarily symbolic. They have not yet seriously interrupted the offensive of the right.

Being on the strategic defensive, however, is not the equivalent of being routed, even though our movements were largely defeated in the 1970s. It means that the momentum has mainly been in the hands of the right. And, with the growth of neoliberalism, a rogue’s gallery assumed form, bringing together elements of the political right in an objective united front against the progressive movements.

Tactical victories have been won while we have been on the strategic defensive, including around LGBTQIA rights, and some immigrant rights, but none of this has seized the initiative away from the right. At least not yet.

In a situation of strategic defense, priority must be given to understanding and undermining the strategy of our opponents. Undermine the strategy of one’s opponent and one has undermined one’s opponent.

This is where matters become especially complicated since the political right is not one monolithic monster. The forces that formed the core of what became the New Right were ultraconservative (and in some cases crypto-fascists), with either secular or religious ambitions, that have sought to overturn the major progressive victories of the twentieth century. There has been a specific focus on overturning the victories of oppressed nationalities, racialized populations, and women, in addition to undermining the public sector and labor. The “critical image” for the New Right was the 1950s as the period that was the zenith of the “American Century.” Beginning in the late 1960s, these New Right forces constructed a multilevel assault against progress, including the building of reactionary mass movements (for example, anti-busing, anti-abortion, anti-Panama Canal Treaty), litigation (particularly moves against affirmative action and abortion), and electoral and legislative (including the building of grassroots electoral movements and blocking labor law reform). These reactionary movements arose prior to the full materialization of neoliberalism, but coalesced with the pro-neoliberal forces in the Republican Party. This coalescing came to be personified by the presidency of Ronald Reagan. The Democratic Party establishment increasingly embraced neoliberal economics, but demographically diversified because of the impact of the progressive social movements of the 1960s and ’70s on the Democratic Party itself.38

The political right has had a fragile unity between right-wing populists and more neoliberal authoritarians. The right-wing populists are divided over their relationship to neoliberalism. When the targets of neoliberalism can be “color-ized,” that is, made to appear to be of particular benefit to racialized populations, right-wing populists can be repeatedly mobilized (think of the Tea Party Movement). By the same token, within the ranks of right-wing populism there is a “welfare-ist” wing that wants the benefits of the so-called welfare state but only for what they see as the “legitimate” (read: white) population.39 In Europe this divide is more pronounced than in the United States, probably a reflection of a longer history of stronger labor and socialist movements that had an impact on the larger population (and, ironically, in shaping the manner in which right-wing populism has reemerged in Europe).

Beginning during the period of the Barack Obama administration, ultraconservative capitalists have been quite successful in mobilizing a mass right-wing populist movement to advance neoliberalism. The presidency of Donald Trump demonstrated this. Despite his rhetoric, which frequently tried to center (white) “working people,” his initiatives advanced both the neoliberal agenda as well as his own objectives. Tying all of this to a racist, xenophobic program, he solidified a mass base, the core of which is approximately 25 percent of the electorate; a program which one might describe as the reaffirmation of the “white republic” or, as earlier stated, a campaign for a neo-apartheid state in the United States.

The destruction of the right-wing populist movement, and the New Confederacy, necessitates a combination of driving a wedge between that movement’s base and the ultraconservative capitalists, building a left populist current that is antiracist and antisexist rooted among working people with a particular focus on the achievement of a so-called Green New Deal.

Right-wing populists cannot, by and large, be “picked off” one at a time. They embrace a paradigm that is self-reinforcing and linked together by racism, sexism, and irrationalism. One can see in the attraction of white evangelicals to Trump that they care nothing about his personal behavior but rather about what they believe that he – as a blunt-forced object – can accomplish for their agenda. And even those individuals who speak about economics and would seem to be fertile ground for a progressive message cannot seem to explain, with any degree of coherence, their alignment with a racist, misogynist, and xenophobic administration.

A paradigm crisis within the movement could occur to the extent to which (1) the base sees blatant inconsistencies between the stated objective(s) of the movement and the actual practice as led by the ultraconservative capitalists, and (2) an alternative pole is created that offers a progressive – if not revolutionary – solution to the calamitous circumstances within which millions exist; an alternative offered without falling into the pit of ignoring matters of race, gender, ethnicity, and religion. One outcome of a paradigm crisis can be a shifting to the left, but it is equally possible that the shift will be toward the right, meaning, toward neofascism out of disgust with the capitalists, but with a deep desire for the reemergence of the “white republic” of the small businessperson and entrepreneur.

An assessment of the right-wing populist base must distinguish between those who are confused and vacillating versus those who fully embrace the right-wing populist framework. To win over a segment of this base, genuine organizing must take place among this portion of the population, including but not limited to rural areas, as well as within segments of the working class. This, for instance, makes union organizing in the South and the Southwest of immense importance as a means of building “base areas” for progressive politics. That said, the approach toward union organizing must itself be transformed such that not only are the strategies novel, but so too must be the vision. This is what Fernando Gapasin and I were addressing in our book, Solidarity Divided.40

The great and immediate priority, however, is for the socialist left to cohere organizationally (building a national left organization) and to focus our attention on a counter-project. Specifically, we need to build a popular democratic bloc that is majoritarian in orientation, antiracist and antisexist in program and practice, and most immediately fights in favor of a progressive, democratic foreign policy, breaking with imperial privilege, and focuses on advancing the fight for the Third Reconstruction with a particular emphasis on winning a Green New Deal. Such a movement can reject both the neo-Confederacy as well as the neoliberal approach taken by the leaderships of both major parties.

Disrupting the strategy of our opponents necessitates tactical innovation and creativity. This includes, in the immediate, anti-voter suppression work, particularly in the South and Southwest; battles for Indigenous sovereignty; union organizing and labor struggles that challenge income, wealth inequality, and authoritarian workplaces; land occupation and anti-eviction struggles; challenges to police abuse and other forms of repression; and electoral campaigns in low turnout conservative districts. These constitute a variety of means to disrupt the other side. In essence, the progressive forces serve to become the unpredictable irritant.

To begin to shift the balance of forces, the progressive – left populist – movement must focus on an achievable objective: “governing power” in municipalities, counties, and eventually states. “Governing power” references winning progressive power within the context of so-called democratic capitalism rather than “state power,” the latter referencing the period of being the dominant force in moving postcapitalist, fundamental social transformation. To put it more directly, the fight for governing power is what we do now, as part of our effort to build the Third Reconstruction and defeat the New Confederacy. This does not assume the immediate end to capitalism. The fight for “state power,” however, is the longer-term fight to advance full social transformation away from capitalism under the leadership of the oppressed, including but not limited to the working class.

New Majority, a term that began to appear in the early 2000s and came to be associated with projects in Virginia and Florida, or Twenty-First-Century Majority, are good frames and identities for the left populist – structural reform – movement that needs to be constructed. The New Majority must be the mass base of the Third Reconstruction. This term expresses the reality of something different coming into being – particularly the rise of various social forces and movements – and the refusal to be seen as a minority or adjunct social force. The New Majority must push the limits of democratic capitalism under the banner of the fight for consistent democracy. New Majority, a term primarily used in different forms in the context of electoral efforts, can be applied to other social movements and be the identity or standard under which progressive social movements converge.

The New Majority (or left/progressive bloc) needs to win power in cities and counties but cannot afford to be limited to an urban movement. Therefore, eyeing political power at the state level becomes critical. A successful Republican ploy to undermine liberals and progressives in major urban centers has been “state preemption,” that is, limiting the ability of localities to undertake statutory reforms in the absence of the approval of state legislatures. Thus, a strategy to win must engage urban, suburban, and rural populations in the constitution of the New Majority.

Potential Implications

1. Understanding Our Opponents

Most of the US left is much too comfortable treating all the forces of capital – and the entirety of the political right – as one monster. Coupled with this has been our eternal diagnosis that any form of repression carried out by a regime of capital must be evidence of fascism. This latter view implies that capital is ordinarily peaceful and needs another form of rule in order to be repressive. History would dispute such a conclusion.