The Politics of the Mask

The years since Donald Trump’s election have been marked by a resurgence of violent street-level political confrontations. Fascists and their opponents have squared off in numerous cities, while recent protests against racist police violence have grown into a powerful movement. Cities across the country are now in open rebellion.

This new political instability coincides with the tenth anniversary of the publication of critical theorist AK Thompson’s Black Bloc, White Riot: Anti-Globalization and the Genealogy of Dissent (2010), which advanced a provocative thesis regarding the intimate bond between political violence and the white middle class. In Thompson’s account, the black bloc – a demonstration tactic in which masks and sartorial uniformity are used to facilitate participation in confrontational skirmishes – was both seductive and disquieting to white middle-class audiences because it forced them to confront the limits of their own political efficacy. Today, as activists confront the question of violence once again – and COVID-19 universally necessitates the wearing of masks in public – the polarizing debates that inspired the book have reignited, and Thompson’s analysis has implications that reach far beyond the case study that prompted it.

In this interview, I push Thompson to clarify his positions and extend his analysis to consider the forms of street-level political violence we confront today.

— Clare O’Connor

Clare O’Connor (CO): Masks have long figured in the wardrobes of political dissidents. How does the political significance of masks change when they have become part of daily life?

AK Thompson (AKT): From the Boston Tea Party to the current pandemic, public mask-wearing in the United States has tended to coincide with moments of political rupture. The emergence of the black bloc during protests against corporate globalization at the turn of the century, and the rise of Anonymous during the Occupy movement, should also be conceived of in these terms. When considered from the standpoint of their participants’ political aims, each of these episodes seems quite different. What connects them is the fact that, in each case, masks appear at the very moment when people begin struggling to transform their relationship to the state.

Today, we find ourselves in a paradoxical situation in which states are simultaneously criminalizing face covering while at the same time legally demanding it. Whether justified through purported commitments to secularism (as in France), or the need to monitor protestors for prosecutorial ends, states have passed laws against mask wearing and religious head covering that follow logically from a conception of citizenship founded on the recognition of subjects. At the same time, the state’s demand that people wear masks to minimize the pandemic’s reach suspends this reasoning in the interest of maintaining the body politic.

These two contradictory political aims have always coexisted within bourgeois states, which take as their subjects both “people” and “populations.” Intimations of this duality can already be detected in the French Revolution, as when the National Constituent Assembly adopted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. What’s intended by the distinction introduced between these two categories, which nevertheless operate as synonyms within the document? In light of how bourgeois states developed following the Revolution, one can infer that it arose from an intuitive awareness that the terms themselves coincide with two separate political aims – both necessary and antithetical – bound up within the modern state project.

The Trump-endorsed anti-lockdown protests that sprang up in late April gravitated toward a particular conception of the citizen. In contrast, the left has generally supported the suspension of normal activities in the interest of flattening the curve. Consequently, it has tended to align itself with certain aspects of the state’s project for preserving the “man” side of the equation. For the time being, there are factions within the state that continue to support these initiatives, but they seem to be losing ground. Already, shopkeepers in certain parts of the country are demanding that customers not wear masks in their stores, citing recognition-related concerns pertaining to shoplifter prosecution and ID requirements for alcohol and tobacco sales. As of yet, they’re getting little pushback from the state.

To understand why mask-wearing during a pandemic could be conceived as being in violation of citizenship norms, it’s necessary to recall the intimate conceptual bond between the citizen and the individual in bourgeois politics. The individual is the base unit of liberal democracy and the foundation upon which our conception of citizenship is built. Capable of following laws, paying taxes, and casting votes, the individual is ultimately the subject who can be represented. Mask wearing in times of crisis immediately calls the existence of this individual into question.

In the black bloc, the mask becomes a pathway to anonymity. A little further, and it prompts the emergence of forms of collective subjectivity that can’t easily be captured by the legal regime. Following the January 20, 2017, protests against Trump’s inauguration, assistant US attorney Jennifer Kerkhoff tried to charge participants in that day’s anti-capitalist, anti-fascist bloc as a single conspiratorial entity, thus making the whole group responsible for crimes purportedly committed by discrete participants. It didn’t work: Chief Judge Robert Morin of the Superior Court of the District of Columbia refused to try the case on this basis.

The situation is similar with respect to religious head covering, which announces a form of collective belonging that undermines bourgeois conceptions of the individual and implicitly supersedes the demands of the state. Under conditions of Islamophobic reaction (and regardless of individual intentions), the hijab marks a turn away from the state’s injunction to individuate. For this reason, it’s not surprising to see that anti-hijab sentiment is frequently coupled with fears that Sharia will take hold and undermine US sovereignty from within.

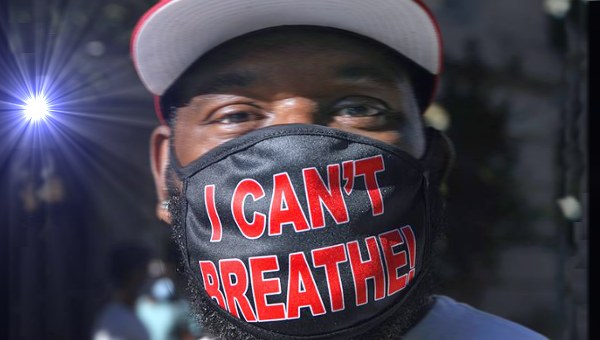

Finally, with the pandemic mask, the myth of the individual comes face to face with the reality of our profound embodied complication. The individual is not easily reconciled with our growing awareness that you’re in my lungs, and I’m in yours. Here, politics reveals itself to be fundamentally respiratory in character. Prior to the pandemic, this reality was highlighted by Black Lives Matter, which turned Eric Garner’s dying words, “I can’t breathe,” into a powerful rallying cry. Today, these same words unite the cities that exploded following the murder of George Floyd. By drawing attention to the bond between politics and the respiratory, the pandemic mask also reveals our corresponding fragility.

The black bloc responds to fragility with anonymity. With religious head covering, vulnerability discovers its antithesis in collective identity. In the midst of a pandemic, collective risk is confronted with a care for life founded not on individuality but mutual aid. Masks mark a threshold beyond which the state’s man-citizen antinomy can no longer be resolved through compromise. At this point, masks themselves become both protective and enabling. They reveal our vulnerability to the world and its sovereign powers, which alternate between prosecuting us as citizens and sacrificing us as “human capital stock.” Concurrently, however, they disrupt the myth of the individual and foster intersubjective bonds that enable us to address this vulnerability directly.

CO: In Black Bloc, White Riot you critique representational politics by juxtaposing representation to production, arguing that only the latter offers a pathway to liberation. Given that Trump is making a second run for office, do you worry that your critique would, if heeded, encourage people to avoid trying to defeat him at the polls?

AKT: In my book, I argued that black bloc violence was both seductive and disconcerting to the white middle class because it made clear that another sort of politics existed beyond representation. Although the black bloc could not move decisively into this new political space, it served as a kind of limit situation for those who remained trapped within the representational sphere. Rather than making demands, black bloc violence tended to open up zones in which new forms of sociality might emerge. In this way, it helped to reveal the intimate connection between violence, production, and politics.

As with strikers who set up picket lines to shut down their workplace, rioters move to secure territory. Following Floyd’s murder, protestors in the Minneapolis riot zone commandeered a hotel and turned it into housing. In Seattle, activists turned Capitol Hill into an autonomous zone following the expulsion of police from the district. Despite their promise, however, experiments of this kind tend to get smashed or collapse for lack of broader support. Consequently, they are recuperated within the representational sphere, where riot-as-production degenerates into riot-as-spectacle. And even when these experiments do disrupt the representational sphere, they must always begin from within it.

So what do we do? In the short term, those who have decided to throw their energy into the election should be pressured to push that struggle as far as it can go. Minimally, this means voting Trump out. Beyond that, it means working to push the Democratic platform as far left as possible. But we should not forget that the current mass insurgency has already done more to prompt political realignment than even the most successful internal party efforts have achieved. Defunding the police and reallocating resources have become popular policy objectives precisely because the negative sanctions imposed by rioters have been so great.

Historically, Democrats have taken black voters for granted, claiming to represent them while offering crumbs. When black freedom struggles have developed significant traction outside the representational sphere, however, they have forced the party to choose between realignment and irrelevance. We saw this clearly during the civil rights movement, which made the party’s alliance with the Dixiecrats untenable. And, as Richard Cloward and Frances Fox Piven have pointed out, one of the major factors contributing to this realignment was a massive decline in electoral participation among black voters in the North. If activists who joined the party hoping for a Sanders victory want to prompt a realignment of this kind today, they are likely to be more effective in the streets than they would be within the machine.

CO: Looking at the riots going on today, people often jump to the conclusion that white participants are agents provocateurs. Does this accurately capture what is going on?

AKT: White people have strong incentives for participating in riots; however, the reasons for this aren’t often understood. As a result, the actions themselves can become a source of confusion. It’s useful, then, to recall how we got here so that we might slowly work our way out.

The bourgeois revolutions that gave rise to representational politics at the end of the eighteenth century produced a paradoxical situation in which states asserted a monopoly on the legitimate use of force while simultaneously declaring that sovereignty resided in the people. For the bourgeoisie, the resolution to this paradox was found in the franchise. Through elections, the people would nominate the state while surrendering their capacity for violence so as not to undermine its monopolistic claim. In the United States, the white middle class emerged as the ideal subject for this new political regime, and its induction into the representational sphere bolstered a sense of innocence that was at odds with the violence to which it remained complicit.

By the mid-twentieth century, however, leading black intellectuals such as James Baldwin and Frantz Fanon began observing that white people had come to pay a significant psychological cost for their privileged estrangement. As Baldwin recounted in The Fire Next Time (1963), white lives were marked by an “uncertainty” that coincided with the foundational disassociation upon which they were based. For those captured by the representational paradigm but not cast as its ideal subjects, this feeling of uncertainty was less acute; however, because the bourgeois political project had totalizing aspirations, it still took hold in various ways. The history of appeals to the authenticating “real” within hip hop culture, for instance, makes little sense when considered outside a system founded on compulsory disarticulation.

These dynamics find expression in social movements, too. The repertoire of action that most movements in the United States draw on today (mass meetings, rallies, marches, and petitions) arose in conjunction with representational politics and the bourgeois public sphere. This repertoire aimed at persuading power to act on the movement’s behalf, and this aim made sense because movement participants could assume that their claims would be recognized. But while this repertoire became culturally dominant within liberal democracies, it was never really available to those for whom recognition could not be presupposed. From the Haitian Revolution right through to the current uprising against racist police, the historical dynamics of black freedom struggles clearly reflect both this exclusion and the means by which it might be overcome.

In Black Skin, White Masks (1952), Fanon argued that recognition could not be viewed as a pathway to liberation: not only did it make you beholden to those in a position to extend it, it also tied your sense of self worth to the whim of another. Although the historical details are different, this situation is analogous to the one in which white people find themselves with respect to representational politics. Fanon proposed that black people disavow recognition so that they might pursue “a restructuring of the world.” For our part, I think white people can follow suit by disavowing representation and the social movement repertoire to which it gave birth. From there, we might finally learn the hard-won lessons of black freedom struggles.

CO: You’ve argued that violence is best understood as a productive relation through which objects become decoupled from their associated concepts. As an example, you recount how “architecture” becomes “property” the minute you set it on fire. This conception has been criticized for being too broad. What, then, do we gain from proceeding as you propose?

AKT: Movement debates about violence tend to be annoying, not least because they reveal how willing we are to confuse the registers of the normative and the analytic. Radicals oppose the state and its monopoly on the legitimate use of force; however, we usually seek to characterize our own actions as being either nonviolent or “nothing when compared to the real violence of the state.” I don’t discount the difference between their violence and ours at the level of scale and intention, and I understand the strategic benefit of trying to stay on the state’s good side. Nevertheless, we must come to terms with the fact that our customary postures end up acceding to the monopoly (if not necessarily to the legitimacy) of the very state we deride.

In contrast, my work begins by bracketing normative claims so that violence can first be understood analytically. This doesn’t mean that norms are unimportant, but it does mean that they shouldn’t be presupposed. This is especially true because the state’s definition of what counts as violent has tended to be extremely elastic, with the result that activists are often left with little room to maneuver if we start by presuming that our actions must always be nonviolent.

Violence involves the transformation of an object through action, and this transformation is given expression through the decoupling of that object from the concept to which it had been bound. Such transformations modify the social field, but not every modification of this kind is recognized to be the result of violence. For this reason, the desire to return to norms at this point can be overwhelming. But rather than resorting to normative distinctions between “good” nonviolent outcomes and “bad” violent ones (distinctions that are always bound to be contested and unstable), it makes more sense analytically to propose that non-recognition is itself a social product. It is the outcome of a violent transformation that accords with prevailing social relations and, for this reason, remains undetected. The correlate, then, must be this: only when the transformation contradicts or supersedes these relations does it become recognizable as violent.

The fact that we don’t consider most of the transformative acts in which we engage to be violent owes not to their innocence but rather to the fact that the outcome has been normatively prescribed and, for this reason, does not cross what I’ve called the threshold of recognizability. Considering the normative changes that have taken place historically regarding spanking one’s child, for instance, we can observe that this threshold is not static. Wherever we confront it, however, we are forced to come to terms with the tremendous violence that flourishes beneath the shadow cast by norms.

The aim here is not to broaden the range of our denunciations. Instead, it is to foster a break with our presumption of innocence so that we might come to terms with the impossible scale of the socially sanctioned violence in which we are already complicit. Only then might we ask: What would I do if the state’s monopoly were broken? What would we produce if the mobilization of our collective capacity for violence were up to us?

When radicals talk about seizing control of the means of production, it’s necessary to clarify that this process applies first and foremost to the democratization of violence itself. It’s not surprising that, in State and Revolution (1917), Lenin argued both for dissolving the standing army and for arming the people as a whole. Similarly, Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) theorized a “divine violence” that would supersede all prior forms by never becoming encoded in law. Logically speaking, such an outcome demands a perfect correspondence between a people and its sovereignty – a correspondence that can only be achieved under the direct rule of the producers.

CO: His name is not nearly as prominent in Black Bloc, White Riot, but your latest book, Premonitions (2018), reveals the extent to which your thinking has been shaped by Benjamin. How has that deepened over the years, and how do you position yourself within the literature on his work?

AKT: Although I now think of myself as a Benjamin scholar, I was only just beginning to grapple with his ideas while I was writing Black Bloc, White Riot. Over the past ten years, my work has become increasingly indebted to his insights, but this intellectual turn placed me in a very crowded field. The secondary literature on Benjamin is vast and uneven, and many of its contributors fail to do justice to his political commitments.

As a German Jew who died fleeing Nazi terror, Benjamin has a lot to teach us as we struggle against encroaching fascism today. In making sense of the current black-led rebellion against police violence, for instance, it’s useful to recall his famous essay on the concept of history. Written just prior to his death, most scholars agree that this essay should be read as a summary of Benjamin’s thought. In its eighth thesis, he advances three key arguments that remain invaluable today.

First, the state of emergency in which we find ourselves is not the exception but the rule. Although Floyd’s murder alerted many white people to the persistence of racist police violence, black organizers (guided by what Benjamin would have referred to as “the tradition of the oppressed”) have made clear that the experience merely confirmed what was already well known in black communities.

Second, coming to terms with the fact that the state of emergency is actually the rule allows us to envision what would be required to bring about what Benjamin called “a real state of emergency.” The violence that exploded following Floyd’s murder can be understood in this light. In contrast to the cops who decide daily upon life and death under the cover of law, the real state of emergency initiates a process of usurpation through which the people themselves experiment with a suspension and subsequent transformation of the law itself.

Third, bringing about such a state will improve our chances in the fight against fascism. During the first week of the uprising, the state began offering concessions in an effort to quell the flames. The popular call to defund the police has already yielded results, and killer cops have been charged with murder. These are aims that previous movements have fought to achieve, but prior to the riots they remained out of reach. Benjamin’s analysis can help explain why we’re seeing these outcomes now. But it can also help to guide our actions – and this is where its true promise lies. •

This interview first published on the Boston Review website.