Beyond the Plague State

It is commonplace when commenting on crises of various stripes to note their capacity suddenly to reveal what the seemingly smooth reproduction of the status quo leaves unremarked, to frontstage the backstage, rip the scales from our eyes, and so on. The character, duration, and sheer scale of the COVID-19 pandemic is a particularly comprehensive illustration of this old apocalyptic truth. From the differential exposure to death engineered by racial capitalism to the fore-grounding of care work, from attention to the lethal conditions of incarceration to a drop in pollution visible to the naked eye, the revelations catalyzed by the pandemic seem as limitless as its ongoing impact on our social relations of production and reproduction.

The political dimension of our collective life is no exception to this. States of alarm and emergency proliferate, veritable sanitary dictatorships are spawned (most egregiously in Hungary), a public health emergency is militarized, and what The Economist dubs a “coronopticon” is varyingly beta-tested on panicked populations. And yet it would be far too simple merely to castigate the various forms of medical authoritarianism that have appeared on the contemporary political stage. Especially for those invested in preserving emancipatory futures in the aftermath of the pandemic, it is crucial to reflect on the profound ambivalence toward the state that this crisis brings to the fore.

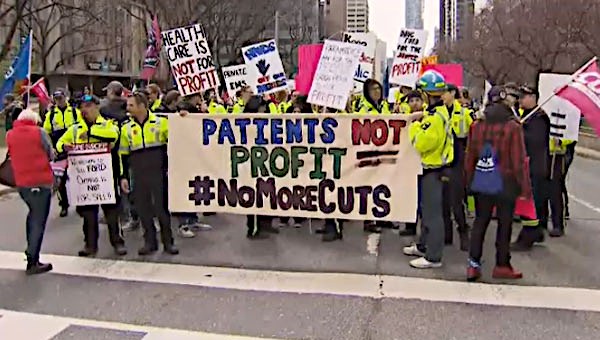

We witness a widespread desire for the state – a demand that public authorities act swiftly and effectively, that they properly resource the epidemiological “front line,” that jobs, livelihoods, and health be secured in the face of an unprecedented interruption of “normality.” And, correcting a hopeful progressive conceit, whereby all repression is top-down in origin, there is also an ambient demand that public authorities swiftly punish those engaging in imprudent or dangerous behaviour.

Declarations of War

Given our cramped political imaginaries and rhetoric – but also, I will argue, the very nature of the state – this desire is overwhelmingly articulated in martial terms. Our ears grow dull with declarations of war on the coronavirus: the US “vector-in-chief,” as Fintan O’Toole has nicely termed him, tweets that “The Invisible Enemy will soon be in full retreat,” while a convalescent UK prime minister talks of “a fight we never picked against an enemy we still don’t entirely understand.” Wayward nationalist analogies to the “Spirit of the Blitz” are trotted out, while wartime legislative powers are enacted temporarily to nationalize industries in order to produce ventilators and personal protective equipment.

Of course, waging war on a virus is ultimately no more cogent than waging war on a noun (i.e., terror), but it is a metaphor deeply embedded both in our thinking about immunity and infection, and in our political vocabulary. As the history of the state and of our perceptions of it testifies, it is often exceedingly difficult to tease apart the medical and the military, whether at the level of ideology or of practice. Yet just as detecting the capitalist hotspots behind this crisis does not exempt us from facing up to our own complicities, so castigating the political incompetence and malevolence that is rife in responses to COVID-19 doesn’t grant us immunity from confronting our own contradictory desire for the state.

The history of political philosophy can perhaps shed some partial light on our predicament. After all, the nexus between the alienation of our political will to a sovereign and the latter’s capacity to preserve the life and health of its subjects, especially in the face of epidemics and plagues, is at the very origins of modern Western political thought – which, for better and very much for worse, continues to shape our common sense. This is perhaps best exemplified by a dictum coined by the ancient Roman statesman and philosopher Cicero and then adopted in the early modern period – that is, the era of the gestation of the modern capitalist state – by Thomas Hobbes, Baruch Spinoza, John Locke, and the Leveller insurgent William Rainsborowe: Salus populi suprema lex (the health of the people should be the supreme law). In this deceptively simple slogan can be identified much of the ambivalence carried by our desire for the state – it can be interpreted as the need to subordinate the exercise of politics to collective welfare, but it can also legitimate the absolute concentration of power in a sovereign that monopolizes the ability to define both what constitutes health and who the people are (with the latter easily mutating into an ethnos or race).

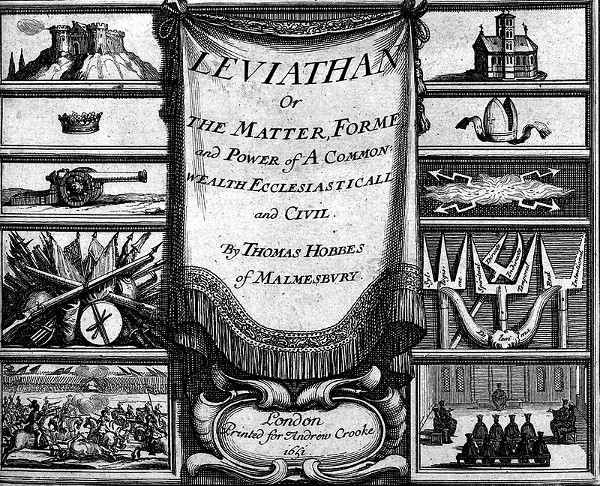

Revisiting our political history and our political imaginaries through Cicero’s slogan, rather than, say, through a single-minded focus on war as the midwife of the modern state, is particularly instructive in our pandemic age. Pick up a copy of Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan (1651) and look at the famous image that likely graces its cover (in the original it was the frontispiece, which faced the title page). You will probably be transfixed by how Hobbes instructed his engraver to depict the sovereign as a head gazing out atop a body politic composed of his subjects (all gazing inward or upward at the king). Or you might scan the landscape to observe the absence of labour in the fields and distant signs of war (roadblocks, war ships on the horizon, plumes of cannon-smoke).

Or you might wander about the icons of secular and religious power arranged on the left and right sides of the image. What you’re likely to miss is that the city over which Hobbes’s Artificial Man looms is almost entirely empty, save for some patrolling soldiers and a couple of ominous figures donning birdlike masks, difficult to make out without magnification. These are plague doctors. War and epidemics are the context for the incorporation of now-powerless subjects into the sovereign, as well as for their seclusion in their homes in times of strife and contagion. Salus populi suprema lex.

In a recent commentary on Hobbes, the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben (whose own editorializing about COVID-19 as merely an opportunity for the intensification of the state of exception has been widely censured) nicely noted that the frontispiece of the Leviathan is a powerful clue to a defining aspect of that modern state which Hobbes’s thinking did so much to shape and legitimize: the absence of the people, or, in Greek, ademia. Hobbes’s plague doctors thus suggest a kind of secret link between, on the one hand, the absence of the people, the demos (as anything other than a multitude to be contained by and alienated into the state’s sovereign), and on the other, the periodic crises elicited by epidemics (literally, “on the people,” epi + demos) and pandemics (literally, “all the people,” pan + demos). The modern state, with its monopoly of power, is a plague state.

From the Politics of Leprosy to the Politics of the Plague

A similar argument, and one pertinent to our times of self-isolation, shielding, and physical distancing, was advanced by the French philosopher Michel Foucault (1926 – 1984). In his lectures on the modern emergence of the social figure of the “abnormal,” Foucault asked himself under what conditions Europe witnessed a shift from forms of rule that excluded, prohibited, and banished, to techniques of power that sought to observe, analyze, and control human beings, to individualize and normalize them. His suggestion was that we turn to the transition between two ways of dealing with infectious disease, from the politics of leprosy to the politics of the plague.

According to Foucault, the move away from a separation between two groups, the sick and the well, as materialized in the leper colonies or lazzaretti, to the meticulous governance of the plague town, household by household, signalled a momentous shift in the governance of our behaviour, ultimately serving as the precondition for our understandings of political power and representation, citizenship and the state. Foucault’s description of the deployment of power in a plague town bears uncanny testimony to the idea that we still largely live in the political space that emerged in eighteenth-century Europe, in what he called the “political dream” of the plague (the “literary dream” of the plague was that of lawlessness and the dissolution of social and individual boundaries):

“The sentries had to be constantly on watch at the end of the streets, and twice a day the inspectors of the quarters and districts had to make their inspection in such a way that nothing that happened in the town could escape their gaze. And everything thus observed had to be permanently recorded by means of this kind of visual examination and by entering all information in big registers… It is not exclusion but quarantine. It is not a question of driving out individuals but rather of establishing and fixing them, of giving them their own place, of assigning places and of defining presences and subdivided presences. Not rejection but inclusion. You can see that there is no longer a kind of global division between two types or groups of population, one that is pure and the other impure, one that has leprosy and the other that does not. Rather, there is a series of fine and constantly observed differences between individuals who are ill and those who are not. It is a question of individualization; the division and subdivision of power extending to the fine grain of individuality.”1

Where the enclosure of lepers operated on the stark group division between the sick (that is, the contagious) and the healthy, the policing of the plague works on gradations of risk, mapping individual behaviour and susceptibility onto cities, territories, and mobilities. It is not a moral or medical norm that is at stake here, but a continuous effort to normalize the behaviour of individuals, each and every one becoming the bearer of a potential threat that can only be managed through data collection (the big registers carried by the watchmen). The government of the plague is thus a precursor of the political obsession with the “dangerous individual,” which brings together (and confuses) phenomena of contagion, crime, or conflict.

In the age of surveillance capitalism and algorithmic power, normalizing practices targeted at the dangerous individual accrue enormous computational force, finer and finer grain. But they are also, like Daniel Defoe’s narratives of self-isolation in A Journal of the Plague Year, an increasingly voluntary affair, while the prolongation of the pandemic and its threat to individual and collective health can serve as a compelling argument not just for the intensification in the powers of the state, but for that examination and registering, that relativization of “privacy,” of which Foucault’s plague town was the dramatic precursor.

Imagining New Forms of Public Health

In view of this long and deeply entrenched history of the plague state, of plague power, is it possible to imagine forms of public health that wouldn’t simply be synonymous with the health of the state, responses to pandemics that wouldn’t further entrench our desire for and collusion with sovereign monopolies of power? Can we avoid the seemingly intractable tendency to treat crises as opportunities for a further widening and deepening of state powers, in the absence and isolation of the people? The recent history of epidemics in West Africa has suggested the vital significance of epidemiologists thinking like communities, and communities thinking like epidemiologists2 – drawing on local moral economies and observations to reshape social and bodily behaviour in a preventative direction – while critical thinking on the limits of “lockdown” policies without the institution of “community shields” moves in a similar direction.3

Pandemics need not be thought of, by analogy with war, as biological arguments for the centralization of power. If the postwar period that persists as the lost object of much left melancholy was characterized by the welfare-warfare state, the exit out of our predicament need not accept welfare-as-warfare as its only horizon. This is especially the case once we reflect on the profound contradictions now tearing at the seams of government between epidemiological and public health priorities, on the one hand, and capitalist imperatives, on the other. In other words, when the health of the people and their social reproduction has been profoundly entangled with the imperatives of accumulation – the very ones determining the contribution of agribusiness to the present crisis and the dereliction of big pharma in alleviating it – the state may be intrinsically incapable of thinking like an epidemiologist.

One speculative avenue for how to begin to separate our desire for the state from our need for collective health involves turning our attention to the traditions of what we could call “dual biopower,” namely the collective attempt politically to appropriate aspects of social reproduction, from housing to medicine, that state and capital have abandoned or rendered unbearably exclusionary, in an engineered “epidemic of insecurity.”4 Public (or popular or communal) health has not just been the vector for the state’s recurrent power-grab, it has also served as the fulcrum from which to imagine the dismantling of capitalist social forms and relations without relying on the premise of a political break in the operations of power, without waiting for the revolutionary day after. The brutally repressed experiments of the Black Panthers with breakfast programs, sickle-cell anemia screening, and an alternative health service are just one of many anti-systemic instances of this kind of grassroots initiative.

The great challenge for the present is to think not just how such political experiments can be replicated in a variety of social and epidemiological conditions, but how they can be scaled up and co-ordinated – while not giving up the state itself as an arena of struggle and demands. The slogan that the Panthers adopted for their programs is perhaps a fitting counter and replacement for the Hobbesian link between health, law, and the state: Survival Pending Revolution. •

This essay first published in Sick of the System, Between the Lines, 2020.

Endnotes

- Michel Foucault, Abnormal: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1974–1975, trans. Graham Burchell (London: Verso, 2003), 45–46.

- Alex de Waal, “New Pathogen, Old Politics,” Boston Review, April 3, 2020, with reference to Paul Richards’s book, based on his research in Sierra Leone, Ebola: How a People’s Science Helped End an Epidemic (London: Zed Books, 2016).

- Anthony Costello, “Despite What Matt Hancock Says, the Government’s Policy Is Still Herd Immunity,” Guardian, April 3, 2020.

- “Interview: Dr. Abdul El-Sayed on the Politics of COVID-19,” Current Affairs, April 7, 2020.