Where is Canada’s Socialist Resurgence?

Socialism is back, at least south of the border. The popularity of Bernie Sanders, the election of open socialists such as Kshama Sawant, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (AOC) and Ilhan Omar, the growth of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) and the teacher strike wave across many ‘red states’ are just some of the signs that socialism is on the rise in the United States of America.

The growth of socialism is just one side of the political polarization taking place in the United States. The surge of the far-right and the confidence Trump has empowered racists and reactionaries everywhere is extremely troubling. This dynamic of political polarization is occurring in many advanced capitalist countries such as France, the UK, Spain and Germany.

The growth of socialism is just one side of the political polarization taking place in the United States. The surge of the far-right and the confidence Trump has empowered racists and reactionaries everywhere is extremely troubling. This dynamic of political polarization is occurring in many advanced capitalist countries such as France, the UK, Spain and Germany.

In Canada, except for Quebec, this dynamic has been more muted. Political polarization is happening to a certain extent. Economic inequality, which is undergirding the political polarization across the world since the Great Recession, is growing in Canada, but to a lesser degree than in the United States. Political and social institutions have remained comparatively stable in Canada compared to many other countries. For socialists in Canada, outside Quebec, this gulf between a socialist revival in the United States and the marginalization of socialist ideas, action, and organization at home can seem perplexing, even frustrating.

A failure to adequately understand this difference can lead socialists in Canada to look for quick fixes: a rush to find our Sanders, our AOC, our version of the DSA.

So why has socialism in Canada not seen the resurgence it has in the United States? To understand the divergent experience in Canada and the United States it is important to understand the economic conditions, the political factors and the sequence of events that explains why socialism is on the rise in United States, but not in Canada.

Economic Inequality

The economic context in the United States is more dire for workers than in Canada. The United States and Canada have both experienced a growth in inequality over the last 30 years. But in the United States inequality and the rate at which it has grown outstrips inequality in Canada. Canada’s Gini Coefficent, which measures income distribution inequality, ranks amongst the middle in OECD countries, while the United States is near the top.

The economic context in the United States is more dire for workers than in Canada. The United States and Canada have both experienced a growth in inequality over the last 30 years. But in the United States inequality and the rate at which it has grown outstrips inequality in Canada. Canada’s Gini Coefficent, which measures income distribution inequality, ranks amongst the middle in OECD countries, while the United States is near the top.

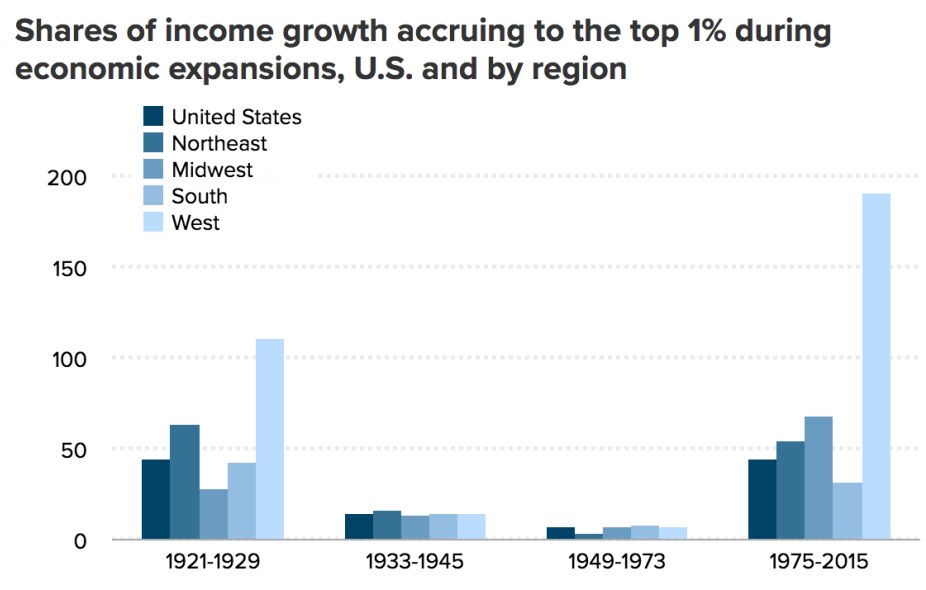

In 2015, the top 1% in the United States took home 22% of all income in the United States. Their share of income in 1973 was 9%. The richest 5% of U.S. households had an average income 14.8 times higher than the poorest 20% of households. Those at the top of the income ladder in the United States are not only seeing their earnings grow, but the rate of growth far outstrips median and low-income earners. When measured by wealth, inequality is even starker.

The top 0.1% of the U.S. population owns roughly 20% of the wealth, more than the bottom 80% of the population combined. The top 10% owns more than 70% of wealth in the country, double that of the bottom 90%. The accumulation of wealth by the super-rich has seen a dramatic rise over last 30 years. Inequality, both in incomes and wealth, in terms of race is staggering and has only grown since the Great Recession.

The top 0.1% of the U.S. population owns roughly 20% of the wealth, more than the bottom 80% of the population combined. The top 10% owns more than 70% of wealth in the country, double that of the bottom 90%. The accumulation of wealth by the super-rich has seen a dramatic rise over last 30 years. Inequality, both in incomes and wealth, in terms of race is staggering and has only grown since the Great Recession.

As Andrew Jackson notes, the top 1% in Canada had a median total pretax income of $234,130 in 2015. This is an increase of 14.5% from 2005. The top 1% had incomes at least 6.8 times higher than the median in 2015, up from 6.7 times as much in 2005 and 5.8 times as much in 1995. Over the same period the bottom 10% saw their income decrease by 10.5%, the bottom 20 per cent saw their incomes increase by a marginal 1.7%.

The income gap between the rich and the middle and low income earners increased in Canada between 2005 and 2015. But the rate of the increase of this income gap was actually larger between 1995 and 2005.

When measured by wealth, inequality in Canada is worse and growing at a faster rate. The top 1% held 11.2% of Canada’s total income in 2015, up from 10.3% in 2014. The bottom 20% have no net worth, and the bottom 40% collectively own just 2.3% of all net worth. The super rich’s share of the pie is growing astronomically, with the number of people in Canada with a net worth of $30-million increased by nearly 14% from 2016 to 2017 (the total wealth of those who had at least $30-million increased by 15% in the last year – and 37% since 2012). Canada has one of the highest densities of the ultra rich in the world. But when we look at the total share of wealth going to the top 10%, the amount they own has remained relatively stable since 2012.

Inequality in Canada is bad and getting worse. But by an absolute measure of inequality and the rate of inequality growth (both in terms of wealth and income) the United States is comparatively a more unequal society.

Public Health

When we factor in things like public services, labour protections, and the social determinants of health the economic conditions for the working class are much more dire. The public healthcare system in Canada is under attack via underfunding and creeping privatization in almost every province. But in terms of access, the quality of care and social outcomes of Canada’s public healthcare system fares better than the mess that is the U.S. healthcare system, despite the latter spending more per capita on healthcare as a society. For instance, in terms of life expectancy the United States is at 78.8 years while in Canada it is 81.7 years.

In 2017, 28.5 million people in the United States did not have any health insurance at any point during that year. Tens of millions more had inadequate insurance or had gaps in their coverage through the year. Of those that did have health insurance, 67% were covered by private insurance, while 38% were covered by public insurance. Employer-based insurance is the most common form of coverage. The lack of universal public health coverage means greater insecurity for workers if they lose their job.

The lack of healthcare coverage and irrational healthcare spending in the United States due to the for-profit system mirrors and helps bolster growing inequality. There is a 20-year life-expectancy gap between the country’s healthiest and least healthy counties. These counties reflect the growing socio-economic divide in the country. Life expectancy in the United States has actually decreased over the last three years. But not everyone is equally impacted. From 2000 to 2014 the life expectancy of the rich increased by 5 years, for poor Americans life expectancy barely changed. In Canada life expectancy has increased for all groups, though rich men have seen the greatest gains.

Public Services

Public services, social “entitlements” and regulations in the United States have been gutted to a far greater degree at both the federal and state levels than they have been in Canada. For instance, while unemployment insurance varies from state to state in the United States the national rate of the unemployed who receive Unemployment Insurance was only 27.5% in 2015. In Canada, the rate of Employment Insurance coverage was slightly below 40% in 2015. Social assistance on both sides of the border is a nightmare, but the right-wing’s ability to push through policies lowering eligibility and rates of welfare in the United States has been greater.

Education spending and policies are also a point of differentiation between Canada and the United States. In both countries public education has been subjected to major cuts and policy attacks. But there is little doubt that those attacks on the public education system, with the growth of charter schools and attacks on public sector unions, has been far worse in the United States.

On top of that the student debt crisis in the United States is reaching absurd levels with $1.5-trillion in aggregate student loan debts. The average student in the class of 2016 in the United States has $37,172 (USD) in student loan debt. Rising tuition fees in Canada are a major issue with the average Canadian university graduate finishing school with more than $26,000 in student debt.

All this is to say that there are material conditions at the root of the socialist upsurge in the United States. By every discernible metric, economic inequality and economic stress on the working class is worse in the United States than in Canada. Economic conditions for workers in Canada are bad and getting much worse. In the United States the economy for workers is going from worse to broken. This is the economic situation that is driving people to look for alternatives.

Political Breakdown

It would be mechanical and foolish to argue that the degradation of public services, work and daily life has automatically led to the socialist resurgence in the United States. Trotsky long ago observed, “In general, there is no automatic dependence of the proletarian revolutionary movement upon a crisis. There is only a dialectical interaction.” Just because workers are being beaten down it does not follow that they are more willing to fight for reforms. The material conditions of inequality is the basis for this resurgence, but not its cause. The rise of socialism is the outcome of a whole series of political struggles that led it to sprout in the current political terrain.

Republican and Democratic adherence to the ruling class project of neoliberalism since the late 1970s has sowed the seeds of the political instability that came home to roost in 2016.

As social entitlements, regulations and workers’ rights were aggressively rolled back, the political ground shifted ever more rightward. The traditional liberal-labour coalition that was a mainstay in the Democratic Party faded, superseded by the pro-corporate wing of the party, the Democratic Business Council and the Democratic Leadership Council in the 1980s. The Democrats proceeded to gut welfare, deregulate the banks, fail to rollback Reagan’s assault on unions and carried out the same pro-war militaristic policies as the Republicans.

The Democratic Party that emerged from the 1980s was a coalition that fused together tech, healthcare and Wall Street capital, the costal liberal upper middle class, and solid African-American and increasingly Latino voting blocs. Elite favoured policies were couched with woke words. The Republican Party meanwhile cobbled together elements of the Christian right and the business lobby. The results were an ever more radicalized Republican voting bloc that was able to win at the state level but mostly confined to ‘middle America’.

The political class as a whole, both Republican and Democratic parties, was upended by two major political events in the 21st century: the Iraq War and the Great Recession.

The lies sold about the Iraq War, that Americans would be greeted as liberators, that it would bring democracy to the region, that WMDs would be found, that Saddam Hussein was an imminent threat turned out to be way off base. This all-party consensus position on Iraq had damaged the political establishment in both parties, but especially the Democratic Party.

In both the 2008 and 2016 Democratic primaries and in the 2016 Republican Party, the Iraq War became a key litmus test. Establishment Democrats and Republicans were tarnished by their support of the war. In 2008 Obama partly distinguished himself from Hillary Clinton because he could credibly say he opposed the Iraq War. Both Sanders and Trump used their opponents support for the Iraq War to great effect. The entire political establishment was delegitmized by its support for the Iraq War.

Illegitimate Institutions

From the Arab Spring to the crisis in the EU, the Great Recession has had a profound impact on the political terrain across the globe. In the United States the all party consensus for neoliberal policies was cracked by the depth of the economic crisis. Both parties supported bailing out the banks, while leaving millions of unemployed and homeless workers hanging out to dry. The Great Recession not only delegitimized the political establishment, it left people desperate and angry with a system that looked like it only cared about the well-off. As Adam Tooze noted:

“Since 2007 the scale of the financial crisis has placed that relationship between democratic politics and the demands of the capitalist governance under immense strain. Above all, this strain has manifested itself not in a crisis of popular participation, or the ultimate control of policy by elected leaders, but in a crisis in the political parties that have historically mediated the two. It has tested their programs, their coherence and their ability to mobilize support, and they have been found wanting.”

Both the Republican and Democratic parties have been going through a profound transformation since 2008 precisely because the establishment has no easy answers for either the political or economic challenges they face in what Michael Roberts aptly calls the Long Depression. A Republican President openly advocating for increased protectionism and trade wars, while the most popular politician in the country is an open socialist is not something that was imaginable a few years earlier.

In Canada, there has not been a similar upending of the political landscape. Outside of Quebec no new party has risen on the left or right to capture part of the political terrain. Andrew Scheer, while odious, does not represent a break from Harperism in the Conservative Party, nor does Jagmeet Singh’s leadership in the NDP represent a sea-change from Laytonism in the NDP. It is remarkable how stable thus far (minus some isolated changes in New Brunswick and PEI, and the larger shift in Quebec) Canadian political parties (outside Quebec) have been.

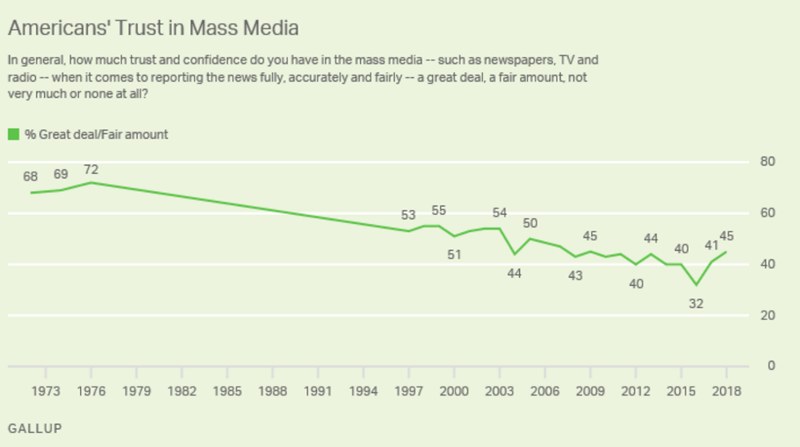

In the United States, it is not just the political institutions that are in crisis, but the whole U.S. establishment. Trust in the government is at record lows with only 17% saying they trust the government. In 2002, that number was at 46%. Trust in mass media is near record lows. In 2003, some 54% had trust in the mass media, now that trust is at or below 45%. In 1976, the trust in the media peaked at 72%. Trust in big business, banks, the church, congress are all noticeably lower than in the early 2000s. Only one institution, the military, has seen an increase in trust in the last number of years.

In the United States, it is not just the political institutions that are in crisis, but the whole U.S. establishment. Trust in the government is at record lows with only 17% saying they trust the government. In 2002, that number was at 46%. Trust in mass media is near record lows. In 2003, some 54% had trust in the mass media, now that trust is at or below 45%. In 1976, the trust in the media peaked at 72%. Trust in big business, banks, the church, congress are all noticeably lower than in the early 2000s. Only one institution, the military, has seen an increase in trust in the last number of years.

In Canada, trust in institutions has dipped, but remains relatively higher. For instance, a 2018 Ipsos poll found that 65% of Canadians trust the media, down 4% from 2017, but still much higher than in the United States. The Edelman Trust Barometer for 2018 found disparities across the board when comparing American and Canadian trust in institutions.

Social Democracy and Unions

Perhaps the biggest difference between the United States and the Canadian left is the state of the institutions of the working class. Canada has an existing social democratic party, the New Democratic Party (NDP), that despite its many faults has remained the default political institution for the working class. The NDP is seen by the establishment as a working class trade union party and its voting base is disproportionately working class voters.

Since 2011 there is little doubt the party has been in a prolonged crisis. Its long march to the political centre has not led to overwhelming electoral success. Decades of accommodating to the political agenda set by business has left the party unable to pull the political debate to the left. Despite the best efforts of party strategists, the NDP has also failed to replace the Liberal Party in the fashion that the UK’s Labour Party eclipsed the Liberal Party. Nonetheless, the existence of the NDP is political pole on the left, that by its very existence has at times forced the Liberals to the left on policy questions. The NDP simply has no equivalence in the United States.

The other major difference between Canada and the United States is the state of labour unions. Union density in Canada has dropped from its high point of almost 40% in the early 1980s to slightly more than 28% today. In the public sector, union density is around 70%, while in the private sector it is below 15%. In the United States, union density has been falling steadily since the 1950s. In 1983, union density rate was 20.1%, in 2018 it is 10.5%. Public sector union density was 34% in 2018, while the private sector union density rate was 6.4%. The union density rate is likely to decline significantly after the 2018 Janus decision which brought in right-to-work for public sector unions in the United States.

The other major difference between Canada and the United States is the state of labour unions. Union density in Canada has dropped from its high point of almost 40% in the early 1980s to slightly more than 28% today. In the public sector, union density is around 70%, while in the private sector it is below 15%. In the United States, union density has been falling steadily since the 1950s. In 1983, union density rate was 20.1%, in 2018 it is 10.5%. Public sector union density was 34% in 2018, while the private sector union density rate was 6.4%. The union density rate is likely to decline significantly after the 2018 Janus decision which brought in right-to-work for public sector unions in the United States.

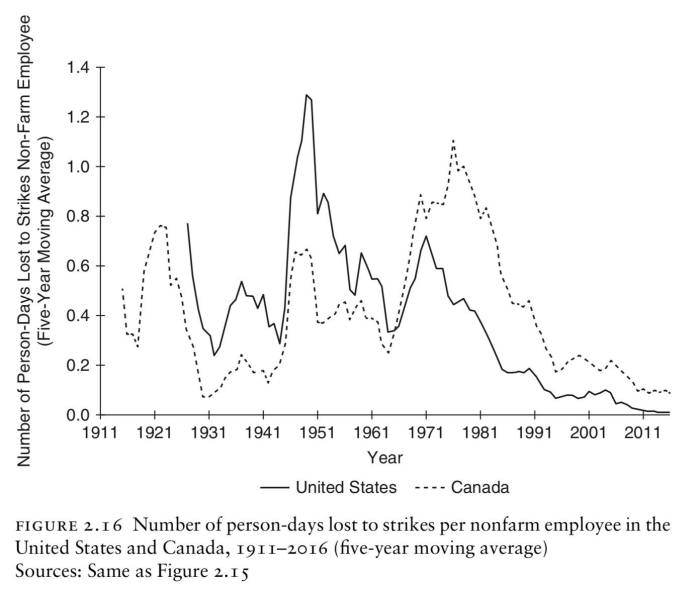

The decline of strikes has been relatively similar in terms of trajectory in both the United States and in Canada. But it is obvious that before 2018 the number of strikes and person days lost to strikes in the United States were relatively fewer than in Canada.

The Socialist Revival

All this is to say that the relative stability of trade unions and the existence of the NDP has helped to militate against the most extreme attacks on the working class in Canada. Whatever their shortcomings, both the NDP and trade unions remain an institutional force within working class life in Canada.

The absence of an established social democratic party in the midst of growing inequality and a political establishment with waning credibility has created the conditions for a vibrant socialist left to emerge in the United States. While the conditions created this possibility, the actual emergence of the socialist left was the product of real movements.

The Wisconsin uprising, the occupy moment, the Fight for $15, Black Lives Matter, #NODAPL, the fight for immigrant rights, the battle over access to abortion, LGBTQ organizing and the new environmental movement – all were addressing systemic issues, creating new networks of workers in struggle and laying the basis for the socialist moment to emerge by shifting the political terrain to the left.

Alongside these movements emerged a new vibrant socialist intellectual current (Jacobin magazine being the most well known publication, but by no means the only one) that have aimed to popularize socialist ideas and perspectives. This socialist current is diverse, contradictory, full of tension and newly emerging.

The organized political expression of this new socialist ferment is the DSA. Before 2015 the DSA had a couple of thousand members and relatively few activists. Formed in 1982, the DSA was from the beginning the social democratic political organization that aimed to push the Democratic Party to the left.

Bernie Sanders’ bid for the nomination in the Democratic Party gave voice to millions of Americans who were frustrated with a society that seemed to only benefit the needs of the rich. Sanders helped to popularize socialism and polarize American politics along class lines.

As the appeal of socialism grew out of the Sanders campaign, the DSA was flooded with new members. Because it already existed, had politics that approximately reflected the movement around Sanders, and had built in links with the new socialist intellectual current the DSA was well positioned to grow out of the Sanders campaign and Trump victory. Over the last three years it has grown from 5,000 members to roughly 60,000 members. During this time a number of DSA members have been elected at the state, local and congressional level. The DSA has new formalized caucuses, new publications, and a greater organized presence in the labour movement.

The rise of the new socialist movement in the United States is not reducible to the DSA, but the DSA is the best example of the profound transformation that the left is undergoing. The DSA is in its infancy and has a number of daunting political challenges and tensions it must face. Despite this the dynamism of the socialist left is real in the United States. It is unbridled and unconstrained by traditional institutions and organizations of the working class.

Canada’s Socialist Future

In Canada, the combination of a relatively muted political and economic crisis, the existence of the NDP and the relative strength of the trade union movement, as well as inability of the existing socialist left to navigate these challenges has thus far mediated against emergence of a new socialist movement.

We are entering a period of profound challenges for the left in Canada. The right-wing is on the ascendancy, our movements have never been weaker or more fractured, and there is a real possibility that the next economic crisis the big business lobby and the right-wing will attempt a major attack on the institutional gains made by workers (such as union rights and healthcare). This does not mean there aren’t or won’t be many openings and opportunities for the left to seize in order to transform the political terrain and build the power of the working class. The escalating fight against Ford’s austerity attacks on workers and students in Ontario is proof of real openings for the left.

Political polarization is happening in Canada, but the path the left has to navigate is much different than United States – it is formed by our own histories, contexts and littered with our own particular challenges.

In the United States the rawness and vitality of socialist politics that is emerging is something to take inspiration from. But the particular organizations and strategies arising in that context are not necessarily a blueprint for those of us in the Canadian state. Finding an AOC, a Bernie or building a Canadian DSA, or worse still, squinting our eyes and pretending the NDP is a socialist party are political shortcuts which avoid both a serious analysis of the balance of class forces and the real opportunities that lie before us. •