Locked-Up for Reading: Young Leftists in China Speak Out

Voices from the November 15th Incident

On November 15, 2017, police stormed into a student reading group at the Guangdong University of Technology (GDUT) and seized six participants, including four current students at the university and two recent graduates from other schools. The former were released the next day, but the latter two were placed under detention as suspects for the crime of “gathering crowds to disrupt social order” – a charge we have seen increasingly leveled against multiple feminists, labour activists, striking workers and bloggers over the past five years. Authorities alleged that the reading group was an “anti-party, anti-society organization” that was discussing “sensitive topics.”

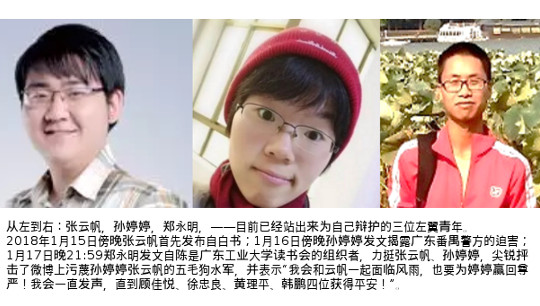

Despite Beijing’s massively staffed policing of the internet and cellular networks, a petition managed to circulate calling for the release of 24-year-old Zhang Yunfan – one of the initial two among what would turn out to be at least four young people detained for weeks as suspects in this case. Apparently the petition mentioned only Zhang, a “Left Maoist,”1 because the authors were unaware of the others when it was penned. Although it was repeatedly blocked only moments after being reposted, over 400 people soon signed the petition, including many prominent intellectuals who risk repercussions because they are based in China.

On January 15, after 30 days in the Panyu Detention Center, two weeks under house arrest and two weeks of recovery, Zhang published the open letter that we have translated below. The letter mentioned three associates who had also been detained and released on bail awaiting trial, and four others who were still in hiding after having been put on the police wanted list.

The next day Sun Tingting, one of the other three detainees, released her own open letter, also translated below. It provides a more detailed account of the arrests, their context and her nightmarish experience in detention from December 8 to January 14.

Like the petition, both of these letters were of course quickly censored, but new WeChat feeds keep popping up and reposting them, to the point that “Sun Tingting” even briefly trended on Sina Weibo until the term was blocked.

Then on the third day, a third letter appeared by yet another detainee: Zheng Yongming. In the interest of making these translations available as quickly as possible, we are publishing the first two now and will add the third when it is finished in a day or two. •

My Confession to the People

Zhang Yunfan

Translated by Steamgoth Engine

Special thanks to Qian Liqun, Zhang Qianfan, Li Ling, Chen Bo, Cai Xiaoming, Song Lei and other mentors from Peking University (PKU), and to Huang Jisu, Kuang Xin’nian, Zhu Dongli, Qin Hui, Yu Jianlin, Xu Youyu, Song Yangbiao, Chen Hongtao, Fan Jinggang and over 400 other mentors and friends from all walks of life, who signed the petition for my release. Thanks for courageously speaking out for justice so that I can again see the light of day! I wish I could express my gratitude to every one of you in person.

I was released on bail awaiting trial December 29th, 2017. However, after 30 days of criminal detention and another 14 under house arrest, I find that the challenge has just begun.

I cannot tear off this page of my life. My only option is to confront the challenge.

Some people say I am a PKU alumnus, a scholar, an elite who is less egotistical than most. But the identity I hold dearest is that of a Marxist and a “Left Maoist” – labels to which different people attach different meanings.

I can see that in this world, exploitation and oppression have never disappeared. Many of my family members have been workers in state-owned enterprises. Thus, even when I was a child, I was aware of how the lifelong hard labour and contributions of old workers were expropriated, when the state-owned enterprises underwent reform and privatization. They were discarded and rendered precarious, abandoned to the will of society. Even larger in number, the vulnerable groups, those in coal mines owned by abusive bosses, on scaffolds and in sweatshops – their life trajectory was to first exhaust their youth, then exhaust their whole lives, and finally to exhaust the lives of their sons and daughters.

I swallowed this industrial sewage, these unemployment documents

Youth stooped at machines die before their time

I swallowed the hustle and the destitution

Swallowed pedestrian bridges, life covered in rust

I can’t swallow any more

All that I’ve swallowed is now gushing out of my throat

Unfurling on the land of my ancestors

Into a disgraceful poem.2

Behind the glory of prosperity, a long shadow, an inch of halo, an inch of blood red. The poet has jumped to his death, but his faith rises slowly from the horizon.

This is why I am determined to be loyal to the working class and why I have faith in Marxism.

Some of the rumors online are true. It is true that when I was studying in Peking University, I was a member of the PKU Marxist Student Group. My comrades at the university and I not only studied theory in our reading group, but also placed ourselves among the downtrodden masses. I gradually found that – after spending countless hours with them singing, dancing, discussing news, screening films and giving English lessons, everywhere I went, I was greeted by workers on campus. In the cafeteria they always gave me a little extra food.

After graduation I came to Guangzhou. My life did not change, except that now I had to work for a living. To put it a bit self-righteously, perhaps, I continued to practice my idealism one step at a time at GDUT. Actually, though, all I did was to attend reading groups and do volunteer work.

During the reading session when we were arrested, we were discussing historical change and social problems from the last few decades, including major historical events, workers’ rights and so on. We discussed how young people should solve these problems. I admit that we also talked about the movement 29 years ago that university students were involved in.3

Some readers must be curious whether my views are indeed “extreme.” Of course, they are not like what you read about in the newspapers or textbooks or watch on TV. By their standards acknowledging the existence of various problems in society alone is already “extremist” enough, and it is undoubtedly even more so to discuss “how to solve” the problems. But every country in the world has its own social problems. Is it truly a crime for one to voice one’s opinions on how to solve them? This is our right! The Constitution states, ambitiously: “Citizens of the People’s Republic of China have freedom of speech, publication, assembly, association, procession and demonstration.” If an expression can be judged as “extremist,” then “freedom” means nothing!

However, I would feel that I was at least being treated with due respect and seriousness if the excuse for my arrest were actually “discussing social issues.” When I was locked up on November 15, the police noted that I worked in education and accused me of “illegal business activities.” Perhaps because of the obvious stupidity of this charge, when I was officially detained, my alleged transgression changed to the crime of “gathering crowds to disrupt social order.” Was I, a 24-year-old young person, powerful enough to disrupt the “work, production, business, teaching, research and medical services” of a university campus covering hundreds of acres? Isn’t it obvious that this is just a trumped-up charge meant to silence me?

I was asked to confess that there was a conspiracy. Was there really a conspiracy? What kind of plotting does a reading group need? Are people involved in plotting when they dance in plazas? Does the simple division of labour necessary for a reading group count as “plotting”?

I was also asked to admit that I had “extremist ideas,” to pledge not to attend reading groups in the future, and to give them names of more people with the same ideas. The cold floor of the detention center, interrogation for eight hours on end, the absolute loneliness under house arrest, the overwhelming spiritual torture – all these are hard to put into words. When I was told that more people would be arrested and my parents would be dragged into this because of my decisions, I have to say, I could not bear the tremendous mental stress. All I wanted to do was to bring it to an end as soon as possible and let my family and friends return to their normal lives, even if that meant I would go to prison. So I compromised. To my surprise, I was finally released on bail. The days under house arrest – the days of absolute loneliness – made me wordless and flat. After a dozen days of recovery, I finally resumed my former self. What I did not expect was that my compromise would turn out to be utterly useless!

Several young people involved in the reading group – Sun Tingting, Zheng Yongming, Ye Jianke – were released on bail along with me. But the young leftists Xu Zhongliang, Huang Ping, Han Peng and my girlfriend Gu Jiayue are still wanted as criminal suspects. Our charges have not been dropped, and they have been forced to become fugitives!

I cannot imagine how the four of them are now. When I close my eyes, it is as if we were back in the guotongqu [parts of China ruled by the Kuomintang during the Civil War]: the roaring police cars, the shrill wail of sirens, the agents with arrest warrants hunting down progressive young men and women who had nowhere to hide.

And I am supposed to remain silent. According to the police, I should be “cautious,” return to a “normal” life, sit peacefully at a desk, henceforth living as a “refined egoist.” But they also want me to bear the burden of an imaginary crime for life, and to stay away from reading groups and the labouring masses I so love.

What’s more, I am also supposed to watch other young leftists be hunted down and arrested!

They are not from prestigious schools. They will not be as fortunate as myself, released because of public opinion. They cannot even get out of Guangzhou. And they do not have a Yan’an to turn to.4 The only thing awaiting them is an indefinite period in prison!

I am out of jail, but my conscience is in handcuffs. I was not tried in court, but I will always face a moral judgment.

Maybe we have always been insignificant. But from now on any young idealist can be arrested, any reading group can be condemned, any nonprofit activity can be controlled, ideas and idealism are taboo, free speech is not worth a penny, and Marx and Mao are mere jokes!

How heartless must one be to simply bow one’s head at this moment?

I have heard many speak of “the golden mean,” saying “take a step back to gain a broader perspective.”

Of course I can understand that they care about me and offer advice in good faith. But how can I leave my comrades and become a “refined egoist”? Moreover, “freedom of speech” is protected by the Constitution, so there is no need for moderation. Mao Zedong Thought takes a clear position, not “the golden mean.” If I “take a step back,” maybe my own situation would improve, but my comrades would fall into an abyss! And if they fall, the dignity of all young idealists would fall with them. It is better to revolt than to live in shame! I can only tell the truth – I will compromise no more. I would rather be in prison than resign myself to this miserable condition.

Good people, I urge you to see: the person you have defended is here. He will not let you down. He will hold his head high and face the coming storm. He is prepared! •

Zhang Yunfan

January 15, 2018

I Am Sun Tingting, I Want to Speak Out

Sun Tingting

Translated by Wen

I am the Sun Tingting mentioned in “Zhang Yunfan: My Confession to the People,” and one of the detainees along with Zhang in the GDUT reading group incident. I was detained by police on December 8th 2017 and released on bail January 4th 2018. I originally did not have the courage to speak out, but I saw Lu Qianqian and others reporting on sexual harassment, and saw the courageous Zhang Yunfan fighting for freedom of expression. As someone whose rights and dignity have also been violated, I cannot stand idly by, and I will not remain silent.

I am Sun Tingting and I want to speak out!

For the first 11 months of 2017, my life and work were as usual, organizing charity events for migrant workers by day, and joining campus workers to dance in public squares by night. I never thought that on the night of December 8th a group of police would raid my apartment, turning the last month of 2017 into a nightmare.

I graduated from Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine in 2016. At university, I came across progressive youth and participated in activities related to social service and the public interest. Their passion, spirit, sincerity and practicality deeply affected me. In serving the underprivileged, I came to realize that public interest work is the best way to help underprivileged workers and peasants at the bottom of society to live with dignity. Since then, I developed a strong inclination toward a career in public interest work. I first worked at a social work organization in Guangzhou’s Tianhe District, and later I worked at another social work organization at Guangzhou’s university district in Panyu. Before I started working there, the organization was already collaborating with a reading group at GDUT. One of my responsibilities was to recruit volunteers for public interest events, so I naturally kept in contact and worked with student volunteers from this reading group, and I assisted campus workers in organizing cultural events such as dances in public squares.

Never in a million years would I have expected to face imprisonment as a result.

On the night of November 15th 2017, students had gathered in a classroom for the reading group as usual. Suddenly, security guards stormed into the classroom, supposedly because someone had reported to the university’s Security and Safety Department that the group was discussing sensitive topics. Police then seized four students [at the university] and two recent graduates [from PKU] who were involved in the reading group, taking them all to the police station. The next day, the four students were released, but the two other people (Zhang Yunfan and Ye Jianke) were placed under criminal detention in the Panyu Detention Centre. I soon learned from the director of my social work organization that the group had been labelled an “anti-party and anti-society” organization. For some time thereafter, students involved in the reading group were regularly visited and warned by university [authorities] and the police, and one of the students lost their scholarship. The reading group soon dissolved. I felt this was very unfortunate because they were some of the most compassionate and capable volunteers I had met, unlike many other college student volunteers who do it to accumulate volunteer time rather than try to take up some grassroots perspective.

But I never thought this would affect me because I was merely working with them to organize events for workers. I kept working as usual, but without the help of volunteers, it was difficult to sustain the public square dance activities.

It was at that moment that a terrible disaster befell me.

At around 10pm on December 8th 2017, my landlord knocked on my door, and when I opened it, a plainclothes police officer and four police in uniform forced themselves into my apartment and asked me for my ID, and for me to cooperate with them. As a young woman living by myself, I was dumbfounded, and did not know what to do with myself. A brief moment of panic was followed by overwhelming rage. I repeatedly asked them to show me their police ID and search warrant, but they refused. They began to search my room, rifling through all my things, paging through books, notebooks and diaries, heaping them into a pile and making me stand to one side as they took pictures.

Then I was taken to Xiaoguowei police station with my mobile phone and computer. They started to ask me about members of the reading group, and I said I didn’t know. The head of the police station threatened me: “you don’t want to talk? You can go die (and said this repeatedly)! Then we’ll give her a random charge, lock her up first and figure it out later!”

When they said that, I thought I was hearing things. What is “assigning a random charge”? So police can just “assign a random charge” to an innocent citizen without evidence? Can the law be used so casually in their hands? Can the personal freedom of individuals be impinged upon so freely in their eyes? Not only did I not know the situation of the members of the reading group, I at least had the right to remain silent when being questioned. Can I be assigned a random charge to pressure me because I don’t know or remain silent?

At 5pm the next day, the police took me back to my apartment and asked me to sign a search warrant, and they started to take books and notebooks including my private diaries and Kindle reader. I was very angry and I did not understand. Is a search warrant a warrant to raid my home? Can they take away any personal belongings including the most private personal diary to be examined by police with a search warrant? Do police not consider the privacy of citizens and the inconvenience to people when their personal belongings are taken away? To be clear, at this time I was not even a suspect to a crime, let alone a criminal, but merely being summoned for questioning.

Back at the police station, the police pulled out another search warrant dated 12pm December 9th 2017, and made me sign it. This was clearly a trick! If the search was at 5pm, how does it become 12pm? And why was there a second search warrant? Did they go search again at 12pm? When I questioned the police, they did not reply and I refused to sign. Then they produced a summons which was dated for the previous day, December 8th, and asked me to sign. I questioned them why they did not show it to me last night, and they said under special circumstances people can be taken away first and showed the summons later. I was absolutely speechless! What special circumstance did I have? Me, a wisp of a 1.6 meter tall recent college graduate – did they think I was going to make an escape or something? I also refused to sign that document.

Even more absurdity followed.

In the evening, the police told me they were applying for both my administrative and criminal detention, and waiting for their superiors to decide on which form of detention. Because of an issue with the system, they could only apply for one form of detention, and decided “on the spot” to apply for criminal detention. During the entire process, they did not present any evidence to prove that I had violated any law, and they still so casually decided a criminal detention. At that moment, I again felt the casual attitude with which the Panyu police treat the law and the freedom and rights of citizens.

And that’s how I was thrown into the detention centre “on the spot,” but this was only the beginning of my real nightmare.

The room I was locked up in had 25 detainees, including drug traffickers, thieves and other criminals of all kinds. As a young woman working on public interest in service to migrant workers, to be locked up with these people made me feel endless irony and sadness. The room only had 15 concrete beds, so I had to sleep on the cold floor. I could not sleep the whole night on the first night under the bright light. My body could not handle coldness, and I felt intense pain on my insides. I kept waking up in the middle of each night. In our cell block there was a fixed bathroom schedule, and I was always placed last, and each time it was my turn the time was already up.

If there was urgent need to use the bathroom outside of scheduled bathroom time, I would be punished by being forced to stand and not allowed to sleep. As a result, I alternated between half-hour sleeps and half-hour standing up, and ended up with less than 4 hours of sleep each night. Because of lack of sleep and limited bathroom use, my body weakened and I felt ill inside. I urinated blood on two occasions and experienced two serious instances of constipation which caused so much pain that I could not sit, stand or walk. If not for my release on bail on January 4th, I feel I could have died from the pain in my cell. My request for an individual room or medical attention were refused and ridiculed. When I absolutely insisted, the doctor in the detention centre just gave me some bottle with no medicine in it!

Beside this, there was no privacy to speak of. There were surveillance cameras everywhere, even when you are changing your clothes or using the bathroom. Why should I suffer such indignity!

I was detained for 26 days, and released on bail on January 4th, 2018. However, the charges still remain.

Throughout the entire process I felt bewildered, and even now, I do not know what I did or what law I violated. The police demanded that I write a confession, and that I write it according to their instructions. But I refused to distort facts. The police threatened that if I do not write in accordance with their wishes, I will be put under house arrest for 6 months. But how can I confess to a crime I did not commit?

I have far too many questions, and so I want to write down my experience, and hope others can answer my questions.

- I am not a criminal, and there is no evidence that I am a major suspect to a crime. Why should I be criminally detained?

- Can the police detain absolutely anyone, and then search for evidence to prove the guilt of that person, and when no evidence is found, simply release the person, but the police will not face any discipline?

- Can police arbitrarily search the residence of any citizen, and take away their personal belongings for an indefinite amount of time?

- If during the course of questioning someone doesn’t answer to the police satisfaction, can they just “make up a charge and figure it out later?”

- Can the police arbitrarily decide on either administrative or criminal detention “on the spot”?

- Should I be bullied in detention, and seen as “uncooperative”, just because I insist on my rights in the face of the police?

- Should I not be treated when I fall sick in detention?

- Does 4 hour of sleep meet the legal requirement of “ensuring that suspects have sufficient time for sleep”?

- Can I only be released on bail after agreeing to a confession in accordance with police instructions?

- When the police detained an innocent person for more than 20 days and confiscated my books, computer, mobile phone, Kindle and other belongings, are these evidence of my crime? When can they be returned to me? I no longer have the money to buy those things.

Finally, I want the police to recognize that I was detained for more than 20 days for no reason, which caused me to lose my job, broke my body, put my family in debt for legal fees to the tune of tens of thousands of yuan in borrowed money, and imprinted criminality upon my life. In the future, it may be very difficult for me to find a job. This incident has laid yet another heavy economic burden on my already poor family!

Why is this happening? These questions puzzle me. It has made me very cautious and has made me feel very insecure. I do not know if I, or people around me, will suffer these abuses once more in the future. I hope friends who read the experiences I have described above to explain all this to me, and I also hope that people can help the other friends also suffering from this same ordeal. Whether I will be given a heavy sentence or declared innocent, at least I will have a clear understanding of it all and some satisfaction! •

Sun Tingting

January 16, 2018

This article, along with the original Chinese letters, were first published at chuangcn.org/2018/01/november-15th.

Endnotes

- ‘Left Maoist’ (毛左) is a political category that has risen to prominence since about 2012 in order to distinguish from those Maoists (known as ‘Right Maoists’ by some of their leftist critics but simply as “Maoists”[毛派] by themselves) with more nationalist and/or reformist orientations. (These categories will be discussed in the second issue of our journal, forthcoming later in 2018.)

- From the poem “I Swallowed a Moon Made of Iron” by Xu Lizhi.

- I.e. the mass movement of 1989 that ended with the June 4th Incident on Tian’anmen Square.

- Having likened the fugitives to Communist Party members hiding underground during the Civil War, Zhang now notes the difference that at least the latter had a base in Yan’an to which they could flee, whereas today’s communists have no such sanctuary – in China or elsewhere.