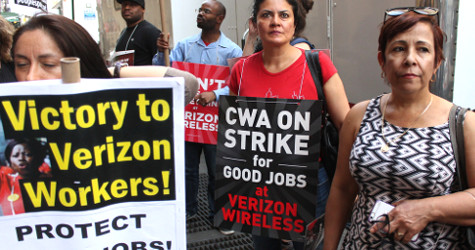

Barb Tiller is a mother of four boys, a wife, and a highly skilled operating-room nurse who has been working at Tufts Medical Center in Boston for 27 years. On July 12, for the first time in her life, she walked off the job along with 1,200 other nurses – almost all women – in the largest nurses’ strike in Massachusetts’s history, and the first in Boston for 31 years. “Nurses don’t stand up for ourselves,” says Tiller. “We stand up for our patients; we stand up for our families when we go home. We stand up for everyone else. But we can’t work under these conditions anymore – like being locked in the operating room with no water, no bathroom break, no meal break, for 12 hours at a time.”

Alyssa Gold, a cardiology nurse whose 16 months at Tufts mirrors the duration of the contract negotiations between the nurses and hospital management, says, “I was excited to start working at Tufts because the best learning for nurses happens in Boston hospitals.” Five years into nursing, which she refers to as her calling, Gold agrees with Tiller about the dire need for change. In the days leading up to the strike, Gold faced some of the fears and self-doubt that hospital managers count on. “Once we sent the 10-day notice to strike, I had to talk myself out of thinking that the daily stress of nursing was my fault,” she says. “I had to be clear that I am not the one deciding to give us too many patients to give the kind of care we all desire to give – management is. And the strike shows what good nurses we are because we are the ones who are trying to fix the situation.”

Alyssa Gold, a cardiology nurse whose 16 months at Tufts mirrors the duration of the contract negotiations between the nurses and hospital management, says, “I was excited to start working at Tufts because the best learning for nurses happens in Boston hospitals.” Five years into nursing, which she refers to as her calling, Gold agrees with Tiller about the dire need for change. In the days leading up to the strike, Gold faced some of the fears and self-doubt that hospital managers count on. “Once we sent the 10-day notice to strike, I had to talk myself out of thinking that the daily stress of nursing was my fault,” she says. “I had to be clear that I am not the one deciding to give us too many patients to give the kind of care we all desire to give – management is. And the strike shows what good nurses we are because we are the ones who are trying to fix the situation.”

The central issue in the Tufts dispute – nurses’ being asked to work way too hard with far too few staff, leading to unsafe conditions, incredible stress, and burn out – is at the root of just about every healthcare dispute in this country, if not every workplace in America. Also at issue in the Tufts strike is the gender pay gap, particularly the retirement gender gap, with a CEO who earns in excess of $1-million demanding an end to the female workforce’s pension plan.

Management: Arrogant and Ignorant

According to Julie Pinkham, a registered nurse and the executive director of the Massachusetts Nurses Association (MNA), what “led to this strike is the arrogance and ignorance of the employer. They seem to think the union is a suggestion box they can ignore. [Management is] a male institution thinking they can snub 1,200 women and pretend their opinions about healthcare don’t count.”

During 35 separate negotiations sessions that began in April 2016, Tufts management dug in its heels. Month after month, the hospital refused to do what every other major hospital in a city that prides itself on providing world-class care has done: respect front-line caregivers. Brigham and Women’s Hospital management, facing a similar situation last year, worked around the clock, channeling their resources into averting a strike by their nurses. Tufts management locked out the striking nurses – and spent at least $6-million just on the wages of strikebreakers they flew in from around the country, and fed and housed in Boston hotels. Brian Doherty, the leader of the Boston Building & Construction Trades Council, says, “This is a working-class city, and we have an employer who is acting way out-of-bounds. None of us knows why Tufts management is taking this tack. But it feels personal to all of us: It feels ideological.”

Boston’s building-trades unions have turned the media stereotype of hard-hat working-class men on its head. When Tufts management announced it was locking out striking nurses and refusing to let them back to work, the Building & Construction Trades Council decided to organize a day-three solidarity march and rally. According to Doherty, “We made leaflets and distributed them to all the downtown construction sites, asking members to take their Friday lunch break with striking nurses. Hundreds showed up to declare that we stand for safe staffing and good wages on our jobs – and in our hospitals.”

The Teamsters sent a letter to the million-dollar CEO of Tufts, Michael Wagner, on July 7, stating that “Teamsters Local 25 will honor and support the MNA picket line. Each day, Local 25 members deliver parcels, freight, medical supplies, equipment, linens, pick up trash and shuttle patients to Tufts Medical Center.” The letter also explained that the Teamsterscare/Blue Cross Blue Shield Insurance plan has paid nearly $29-million in claims to Tufts over the past five years – money Tufts management received because of the Teamsters’ union-negotiated healthcare plan. On July 17 the nurses returned triumphantly to work – with a federal mediator due to arrive on July 24.

Barbara Madeloni, president of the Massachusetts Teachers Association, credits the nurses’ union itself for the outpouring of support. However, Madeloni also points to the strategic leadership of Steve Tolman, the head of the Massachusetts AFL-CIO. “Steve’s been working hard for several years,” Madeloni says, “to help us come to see that the attack is on the common good, that privatization and the attacks on prevailing wages are all the same fight.”

The nurses at Tufts aren’t the only nurses in Massachusetts on strike. On June 26, every single nurse at Baystate Franklin – members of the same union – walked out. And nurses at Berkshire Medical Center began taking a strike authorization vote this week. The nurses in Massachusetts are making a mockery of the idea that workers can’t stand up for themselves, take direct action to end gender-driven pay and retirement disparities, and demand high-quality patient care that doesn’t jeopardize the health of the caregivers.

Super-Majority Strike

To successfully pull off the kind of super-majority strikes being demonstrated by the Tufts nurses, a union has to be democratically run – and prioritize high participation. The MNA is a model of the kind of membership democracy that remains the hallmark of today’s most successful unions. The union’s high participation is seen during contract negotiations, where any member at each hospital can show up and attend negotiations, and where the union negotiating teams talk openly with colleagues about contract talks as they happen.

Perhaps the best evidence of high participation and direct member control at MNA is a strategically brilliant move the union made in 2000, when the membership decided that employers should not be involved in the relationship between them and their union. So they created Union Direct, a program to encourage members to switch from paying dues through an employer payroll-deduction system – still used by almost every other union in the nation – to having members pay dues directly by bank draft or credit card.

“Union Direct, a program to encourage members to switch from paying dues through an employer payroll-deduction system… to having members pay dues directly by bank draft or credit card.”

The late 1990s were a time of huge corporate mergers, with hospitals consolidating power to be able to stand up to insurance companies. But that same corporate consolidation and cooperation among employers also showed up at the contract negotiating table. The nurses understood that if they didn’t make hard strategic choices, they’d soon be overpowered. At the end of Union Direct’s first year, a third of membership was paying dues directly to the union.

To nudge the rest of the nurses to do the same, members voted to impose an administrative fee of $1 per week per member on those continuing to pay through employers. This was done to incentivize nurses, through phase two of the campaign, to shift from giving management control of union money to giving members control of their organization and resources. The union did a mass mailing to members, asking, “Would you like to save $62.40 per year? Switch now to control your money yourself, not your employer.”

Julie Pinkham had just become the union’s director of labor relations. She made the case for why colleagues should pay dues directly, writing that the payroll-deduction system “provides management with information on who is a full member and who is an agency fee member – thus assessing the strength of the bargaining unit in general and by specific area through individual’s work locations. The strength of the union is weakened when the relationship between you and your local unit resides in the technology of your employer.”

Maybe the loss of this inside track is why Tufts management had no idea that 1,200 nurses would actually stand up for themselves. Or why Baystate Franklin was surprised when 100 per cent of the hospital’s nurses walked out over similar issues. In hindsight, Pinkham’s 2000 message was visionary. Right now the Supreme Court is about to take up yet another case, Janus v. AFSCME, which would allow any union member to drop membership despite the contractual benefits they receive from being a member.

MNA Janus-proofed itself in 2000. Because it is a democratic, member-controlled union, its members decided to vote with money, and in tough disputes like the current one with Baystate Franklin and Tufts, vote with their feet by walking out. The MNA is largely composed of and led by women, showing the way to a future where workers can still exercise power in healthcare – one of the few sectors of the economy that is rapidly growing. Union leaders in Boston say the nurses have always been there for them. In return, the nurses are receiving, in Brian Doherty’s words, “total all-out support.” Events in Boston suggest that solidarity may be about to make a comeback. •

This article first published by The Nation.