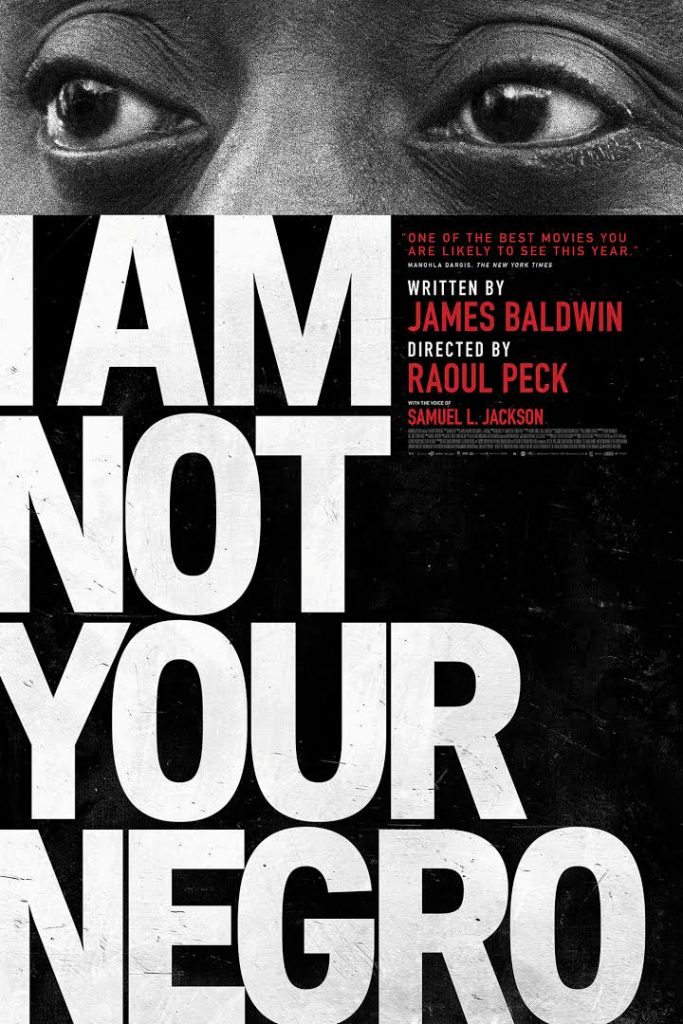

Now and then, and despite its capitalist and racial biases, our culture throws up something that can speak quite eloquently and uniquely about the times we’re living through. In this case, I’m referring to an amazing documentary film that has been released recently, “I Am Not Your Negro,” directed by Raoul Peck, an acclaimed Haitian director with major films to his credit. This latest work is well worth seeing and has been well received here.

A meticulously woven story of the civil rights movement at a critical juncture in its history, expressed in the marvellous words of James Baldwin, the documentary focuses on the lives of three central leaders of that movement in the 1960s, Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcom X, their lives tragically cut short by assassinations, killings that strategically weakened the movement and from which it never recovered.

From a poor and large working class family, Baldwin had emerged on the US scene from the slums of Harlem to become a major writer of his time, even internationally. In the 1940s he exiled himself to Paris to escape the deep homophobia of America, becoming a brilliant novelist and playwright, returning to New York in 1957. He was an extremely articulate propagandist and theorizer of the then rising civil rights movement and powerful voice for black Americans.

The three central leaders of that struggle, Medgar Evers (July 2, 1925 – June 12, 1963), Martin Luther King Jr. (January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) and Malcom X (May 19, 1925 – February 21, 1965), Baldwin had personally known and considered them friends. All were assassinated within five years of each other in the 1960s.

Deemed Dangerous

“(A)ll three were deemed dangerous and therefore disposable,” Raoul Peck, the director says, because “they were eliminating the haze of racial confusion,” in a short book of the same name that was released at the time of the film.

The clever conceit of Peck’s documentary is that it’s based on an incomplete manuscript, thirty pages of notes of a book Baldwin had begun shortly before his untimely death in 1987. The director says that Baldwin “was determined to expose the complex links and similarities among Medgar, Malcolm and Martin. He was going to write his ultimate book, ‘I Remember This House’,” a revolutionary account of their lives.

Peck’s documentary is a brilliant imagining of that unfinished work. In preparing the script, the director relied heavily on Baldwin’s notes that Gloria, a younger sister of Baldwin, generously turned over to him. They are the skeleton for the narrative.

Through a very clever and subtle weaving together of archival footages, interviews, stereotypic images from racist advertizing from the thirties and forties, and from contemporary TV, we are provided with a historical context and an incredible graphic depiction of the momentous civil rights movement that swept the American south in those years, the lunch-counter sit-ins, the courageous fight to integrate the educational system, the voter registration drives, an important part of the history often forgotten.

I admired the film especially for the objective way it treats Malcolm X, who believed black people should unite independently under their own leadership and as a nation to confront the white power structure. Malcolm’s role in history is often distorted, especially in popular accounts in the media which frequently characterize him as a “black racist.” Here in Peck’s documentary, we experience him as a legitimate part of the movement and speaking in his own voice as a revolutionary.

Has Anything Changed?

Seeing on the screen the images of violence of the white mobs and the brutality of the police, reminds us, should we need reminding, that nothing much has changed for black people in America since the murders of these three black leaders. Peck, the director, is telling us something very important here: racism still runs deep in American society.

It’s true that black people are no longer being lynched – and there are shocking images of that from the past in the film – but the lack of improvement in American society for blacks over time, is an idea central to the documentary, which is re-enforced throughout with horrific images from today’s headlines, of the gunning down of many unarmed black people by the police, commonly captured on video by bystanders, witnesses to those events.

The main voice we hear throughout the film articulating this thesis is James Baldwin’s, but the film is also cleverly narrated by Samuel L. Jackson, one of Hollywood’s leading black actors, who gives voice to Baldwin’s words so skilfully it’s as though it’s him we are hearing.

Having become a major public intellectual, the James Baldwin we see in the film was very much in demand for appearances on talk shows and debates about the relationship between blacks and whites in America. He’s beautiful to listen to. We see him entirely at ease patiently putting forward his ideas, restrained and in a beautiful cadence, almost prose and without notes. It’s worth seeing the documentary for that alone.

Seeing and hearing him speak at the Students Union in Cambridge, Britain is a high point. His mastery of his ideas on full display, at the conclusion of his talk he wins a rousing and standing ovation from the students, much to his surprise, if the bemused look on his face is anything to go by. It’s also a reminder that in those years in Britain students were becoming quickly radicalized and responsive to what he had to say. Malcolm X spoke at Oxford around that time and received a similar reception.

But the documentary is not just about a piece of history, it’s very much about today, and should be an inspiration to many of today’s black activists, coming as it does just after the election of Trump, an essential feature of whose campaign was a naked appeal to racism and the encouragement of white identity politics, at a time of increasing violence against blacks in America. For that Raoul Peck should be thanked. I’m sure the film will also have a positive impact in Canada, where the “Black Lives Matter” movement has been on the streets leading a long and determined struggle against the Toronto police department’s policies of racial profiling “carding” practices, of which the overwhelming target has been black people. It will be a boost to the black movement as a whole, on both sides of the border.

I urge you to go and see it, even for a second time, if possible. It has many lessons to teach us. •