In September 2015, a fine document emerged from Canadian progressives around the Leap Manifesto. It expresses a broad will to transform the land around a wide platform of social, democratic and environmental transformation, away from the neoliberal ‘model’ that we endure and fight.

The Manifesto started by identifying violence against the Indigenous Peoples and the non-response from the Canadian State facing climate change as a crime. The priority is to build “an alternative to the profit-gouging of private companies and the remote bureaucracy of some centralized state,” along the lines of a ‘left-green’ project that resembles those of Québec Solidaire or the green-red alliances in Northern Europe.

The Manifesto started by identifying violence against the Indigenous Peoples and the non-response from the Canadian State facing climate change as a crime. The priority is to build “an alternative to the profit-gouging of private companies and the remote bureaucracy of some centralized state,” along the lines of a ‘left-green’ project that resembles those of Québec Solidaire or the green-red alliances in Northern Europe.

When the Manifesto came out, it generated lots of excitement and support. The hypothesis was that it could neutralize some of the divisions that have segmented people’s movements and resistance and diminish the cynicism that many people, especially the younger generation, have about a pseudo Canadian democracy. Although the Manifesto did not respond to all the questions, it was a good start.

Now, it remains to be seen how it can, on the long term, affect Canadian politics and bring together popular movements.

However, there is a blind spot. Much like in the tradition of the Canadian left, the Leapists have ignored the fact that the Canadian state, from its creation till now, is not and cannot be the terrain of emancipation. This state is illegitimate. Its foundations are rotten, since it was erected on class and national oppression, whereas the First Nations on the one side, and the Québécois on the other side, have been dispossessed.[1] To put it bluntly, this state has to be broken and eventually reinvented. Speaking about reforming Canada on the left does not make sense if unless that, from the onset, there is clear and explicit commitment to work with the First Nations and the Québécois by recognizing their right to self-determination and their nationhood.

The Missed Republican Moment

This problem for those who know a bit of the history is not new. For decades, it has poisoned the relations between the Canadian and the Québécois left. It has also created a situation where the bourgeois parties are able to rule steadily in this capitalist country, playing the infamous divide-and-rule game inherited from colonial times.

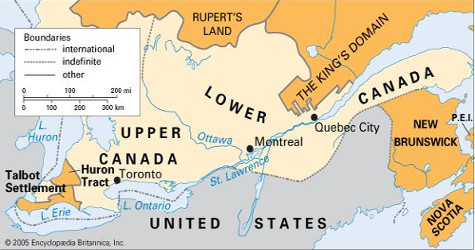

Was it pre-determined to evolve like that? I don’t think so. Indeed, in the 1830s, there was a window of opportunity. An uprising in Lower Canada and important turbulences in Upper Canada raised the banner of independence and republicanism. This movement had the potential to bring together the different nations inhabiting the land and oppose British rule. While the rebellion took the form of a mass insurrection in Lower Canada, it could have eventually broken down the colonial hegemony over the whole land, including in Upper Canada, inhabited mostly by settlers from the British Empire. But at the end, the colonial regime weakened the republican aspirations in Upper Canada by nourishing the fear of an alleged ‘French-Catholic conspiracy’. Militarily, the British Empire was at this point too strong, while the insurrection in Lower Canada had very little strategy. So it was a major defeat, out of which the present-day Canada was born.

The National-Democratic Revolution

The republican movement in Lower Canada attracted tens of thousands of people. In fact the majority of the people, throughout the 1830s, participated in marches and petitions, ‘liberated’ many villages by creating alternative institutions, and elected a majority of pro-republican representatives in the assembly. The ‘Patriotes’ included reformist personalities like Louis-Joseph Papineau, while the masses mobilized around the project were peasants and urban poor. Initially, their demand was moderate, for ‘representative government’ (the elected chamber was deprived of any real power). But when the colonial regime refused any concession, the movement became insurrectionary. The goal was to impose an independent republic with full civil rights for all inhabitants. It included the First Nations, as it is stated in the Declaration of independence: “the People of Lower Canada is exonerated from any allegiance to Great Britain. Under the free government of Lower Canada, all citizens shall have the same rights; the Indians will cease to be subject to any kind of civil disqualification, and will enjoy the same rights as the other citizens of the state.”[2]

In Upper Canada, the republican movement was led by the popular mayor of Toronto, William Lyon Mackenzie, who confronted the colonial regime. In 1837, the ‘reformers’ (the radical wing of the movement in Toronto) called “to make common cause with their fellow-citizens of Upper Canada, whose successful coercion would doubtless be in time visited upon us.”[3] At the end, various disturbances and riots in and around Toronto were put down by the army.

After crushing the rebellion, British rule was consolidated. In 1840, it forced the unification of the two colonies, creating the provinces of Quebec and Ontario, with the explicit purpose of transforming the French-speaking majority of Lower Canada into a minority. On that basis, the colonial regime, in collaboration with an English Canadian elite and their collaborators in Quebec (supported by the reactionary Catholic church), imposed in 1867 the British North American Act (falsely presented as a ‘constitution’). A centralized federal state left residual power to the province of Quebec then put in a position of subalternity.[4] French Canadians were subjected to a regime of harsh assimilation and control. Basically, “the centralized unitary federation of 1867 bore the imprint of inequality: the British-monarchical configuration of the colonial dominion proclaimed a British (and Anglo-Canadian) ascendency and a permanent minority position for the French Canadians.”[5] It transformed the French-Canadian into a cultural minority and denied any political recognition as a national entity.

In parallel, the new regime imposed the infamous ‘Indian act’, stealing 98 per cent of the First Nations’ lands and creating a system of apartheid. In 1885, Prime Minister John A. Macdonald ordered the execution of Louis Riel, the French-speaking Métis leader who led an uprising in Manitoba. 50,000 people demonstrated against this criminal act in Montreal, but Macdonald said, “He will be hanged, even if all the Québécois dogs bark for him.”

The Gap

While a new state was put in place to plunder, oppress and enrich a corrupted political and economic elite, a new people’s movement, by the turn of the century, slowly emerged. It was mostly built by radical trade unions who fought tremendous battles and inspired a first generation of socialists.[6] In 1910, the Socialist Party of Canada wrote in their manifesto that “by political force, the working class must wrest from the capitalist class the reins of government.”[7] In Montreal, the SPC tried to rally immigrant workers, with much less success, however, with French-speaking workers and even less so, with the rural population (the vast majority of the people then). It did not prevent French-Canadians from participating in radical trade-unions and republican and anti-imperialist actions, but it was a serious gap in the attempt to create a genuine and mass socialist movement.

There were several reasons behind the fact that French-Canadians were not attracted to Canadian socialism. The reactionary elites in the province of Quebec, linked to an ultra-conservative Catholic Church, were allowed to build a cultural wall isolating (mostly rural) French-Canadian communities. Canadian socialists, on the other hand, ignored Quebec’s history of class and national struggles. At this early stage, Canadian socialists tended to adopt the European view and reject the idea of national emancipation as a reactionary utopia.[8] For the Second International, Canada was a ‘democratic’ country where there was no national question, since French Canadians were “allowed to use their own laws and their own language as completely as if they had never been annexed.”[9]

Peoples Without History

European socialism remained unable to understand the national question. No one else than Frederick Engels expressed his contempt for ‘small’ nations. Back in 1848, he applauded the conquest of Mexico by the United States, since the “lazy Mexicans” had to give way to the “energetic Yankees” who will “open the Pacific Ocean to civilization.”[10] He also thought that the ‘greater’ European nations had to ‘civilize’ Southern Slavs (Czechs, Croats, Slovenes, Serbs, etc.) and untie “these small, stunted and impotent little nations into a single big state and thereby enabling them to take part in a historical development!”

Engels and to a lesser extent, Marx, were even more off track regarding colonialism.[11] When France conquered North Africa, Engels said it was regretful that the colonized peoples lost their freedom, but one had to consider that “the Bedouins were a nation of robbers.”[12]

Marx explained that British colonialism in India had a “double mission: one destructive, the other regenerating the annihilation of old Asiatic society.”[13] After a while, Marx and Engels toned down. Observing Irish resistance, they understood that England’s ‘first colony’ was miserable not because the people were backward, but because colonization meant systemic starvation and humiliation. They concluded that “the antagonism between the English and the Irish worker is the secret of the impotence of the English working class.”[14] In that sense, socialists, added Marx and Engels, had to support the struggle in Ireland as a necessary step so that socialism could advance. Nonetheless, apart from a few special cases (like Ireland and Poland), they remained broadly convinced that socialists should not be associated with national emancipation demands and movements.

Engels in Montreal

In a short passage to Canada in 1888, Engels made private remarks in his inimitable style:

“Canada is richer in ruined houses than any other country but Ireland. We are trying here to understand the Canadian French – that language beats Yankee English hollow. Here one sees how necessary the feverish speculative spirit of the Americans is for the rapid development of a new country. In ten years this sleepy Canada will be ripe for annexation – even the farmers in Manitoba will demand it themselves. The economic necessity of an infusion of Yankee blood will have its way and abolish this ridiculous boundary line.”[15]

In brief, like the ‘lazy’ Mexicans, Canadians had to give way. Engels’s remarks could be considered anecdotal, but in fact, it was an indicator of a much deeper philosophy.

In the 1880s, he reiterated that he had “no sympathy whatever for the small Slavic peoples, and remnants of peoples.” For Engels, these nations were ‘dwarfs of peoples’. He conceded that in certain contexts, socialists had to “let them take their fate in their own hands,” even if, “six months of independence will suffice for most Austro-Hungarian Slavs to bring them to a point where they will beg to be readmitted!”[16] In the colonial territories, Engels thought that “the countries inhabited by a native population, which are simply subjugated should be taken over for the time being by the proletariat. Once Europe is reorganized, the semi-civilised countries will follow in their wake of their own accord.”[17] This approach percolated deeply into the European dominant socialist culture at that time.

Eduard Bernstein, one of the foremost socialist leaders, said bluntly that “colonies are here to stay (because) civilised peoples have to exercise a certain guardianship over uncivilised peoples.”[18] Even left-wing socialists such as Rosa Luxemburg thought that national demands were not to be supported: “today our national identity cannot be defended by national separatism; it can only be secured through the struggle to overthrow despotism.”[19]

In Russia however, the events changed that course. More than 57 per cent of the population was not Russian in a state composed of over 200 nationalities and where the regime was practicing, according to Lenin, ‘grand-Russianism’ and oppression. The Russian socialists demanded equality between nations and even the right to self-determination. When the tsarist state broke up, many oppressed nations supported the revolution especially that the project was to create a federation of independent states. Toward the colonial situation, the Soviets also went far ahead by promoting anti-imperialist revolts, and imposing on socialists in the colonial countries to side against their ‘own’ state.

Canadian Communism

By the end of the 1910s, impressed by the rise of the Soviets, many Canadian socialists leaned toward the Third International (1919–1943) founded in Moscow. An embryonic Communist Party was set up in 1921, after preventing the new International to recognize a ‘French-Canadian Communist Party’.[20] According to the International, Canadian communists had to support national-democratic and anti-imperialist movements. But Jack Cavanagh, one of the Canadian communist leaders at that time, did not see any relation between Québécois demands for self-determination and liberation movements. In its 1921 Manifesto, Communists had nothing to say about the national question.[21]

On the social-democrat side, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF, 1932-1961) did not acknowledge the national issue in Canada except to say that a new constitutional arrangement was required so that the ‘national’ government should be given more power over the provinces to control national economic development.[22] Indeed, both Communists and Social Democrats advocated a strong central Federal state, which confronted Quebec’s aspiration to a certain degree of autonomy. The Quebec question was then seen, strictly, as a question of language. There was a partial shift later, however.

The Labour-Progressive Party (LPP, 1943-1959),[23] under the influence of Stanley Bréhaut Ryerson, called for the full national equality of French and English-speaking Canadians: “Our party is pledged to fight for the wiping out of the conditions of extreme poverty which weigh upon French Canada as a heritage of the dark past.”[24] Beyond that, Communists remained committed to strengthen the federal state, placing “responsibility upon the Dominion government for social legislation and labor standards, legislation regulating corporations and trade and commerce.”[25] In the meantime, Ryerson continued to argue that the Québécois were a nation, and not a ‘national minority’ or an ethnic group.[26] The Communist Party accepted that in 1950, but it was too little, too late. More than half of the Communists in Quebec had left the Party,[27] complaining that it pretended to promote Québécois rights on the one hand, but advocated for a ‘stronger Canada’ on the other.[28]

The Labour-Progressive Party (LPP, 1943-1959),[23] under the influence of Stanley Bréhaut Ryerson, called for the full national equality of French and English-speaking Canadians: “Our party is pledged to fight for the wiping out of the conditions of extreme poverty which weigh upon French Canada as a heritage of the dark past.”[24] Beyond that, Communists remained committed to strengthen the federal state, placing “responsibility upon the Dominion government for social legislation and labor standards, legislation regulating corporations and trade and commerce.”[25] In the meantime, Ryerson continued to argue that the Québécois were a nation, and not a ‘national minority’ or an ethnic group.[26] The Communist Party accepted that in 1950, but it was too little, too late. More than half of the Communists in Quebec had left the Party,[27] complaining that it pretended to promote Québécois rights on the one hand, but advocated for a ‘stronger Canada’ on the other.[28]

The New Left

By the 1960s, the vast inflow of young Québécois into the left by-passed the Communist Party, as well as the social-democrats (the NDP). This new left was by and large independendist, creating its own utopia in sync with national liberations and new Marxist explorations in the wake of the student and workers’ rebellions of 1968. Since then, the political architecture of the left in Quebec has been largely isolated from Canada, and vice-versa.[29] Apart from radical groups, like those working in the tradition of the Fourth International, the Canadian left did not catch on.

There were exceptions, however, like the NDP-left, the ‘Waffle’, as well as the progressive magazine Canadian Dimension, who advocated earlier on that Canadians should explicitly support Quebec rights. The Waffle wanted Quebec and Canada to join their struggles: “So long as the federal government refuses to protect the country from economic and cultural domination, English Canada is bound to appear to French Canadians simply as part of the United States. An English Canada concerned with its own national survival would create common aspirations that would help to tie the two nations together once more.”[30]

Other left voices supported what became the Québécois left perspective of merging socialism and independence. They were willing to recognize the Québécois nation while preferring that Quebec would come along into some sort of asymmetrical federalism. Revolutionary groups like the League for Socialist Action went further: “we support the decision of the majority for the simple reason that it is the right of the oppressed nation to decide its fate – a basic democratic right. We emphasize this side of the question above all in our work among the workers in the oppressor nation, defending the decision of the masses and their right to make such a decision. And we do so without posing any preconditions.”[31]

The Turbulent 1970s

In 1970, the Pierre Trudeau government violated rights by imposing the war measures act (October 1970). Hundreds of peoples were detained, but instead of crushing the national-social movement, the repression launched a new wave of resistance.

In 1976, the election of the Parti Québécois (PQ) triggered a new round of political crises rocking the State. Four years later, Trudeau defeated the sovereignty referendum of 1980 by lying to Quebec and imposing a consensus of absolute opposition to Quebecois nationalism, which included, by the way, the NDP. During the referendum, the vast majority of the Quebec left campaigned for the “Yes” with a critical angle, keeping away from the PQ which was perceived as a bourgeois pro-capitalist party.[32] After the defeat, the federal state went into an offensive to impose, against Quebec opposition, a new constitution. Trudeau manoeuvered with the direct support of provincial NDP governments in isolating Quebec and so was another step toward federal centralization and denial of national rights. At the end of the decade, the neoliberal Progressive Conservative Party led by a corrupt politician thought that it could reintegrate Quebec through a mild decentralization conceding more residual rights. The rejection of that soft compromise by many Canadian political actors was a surprise and a slap in the face of Quebec, which triggered a second Quebec referendum in 1995.

This time, the federal government with the unanimous support of the Canadian elite illegally entered into the process by injecting illegally vast amounts of resources to derail the process. Confronting that, Quebec trade unions, community organizations, the women’s movement and almost every sector of the left came in the “Yes” campaign that was beaten at the finishing line by a tiny margin. In Canada, a trickle of trade unions (the Postal Workers for one) had the courage to support the right of the Québécois to self-determination, along with the radical left and a few personalities like Margaret Atwood. Some Canadians on the political left, justified their stand because the PQ was ‘not enough on the left’.

The defeat of the second referendum was the beginning of the end of that political cycle. To prevent another possible breakdown, the federal government invested in a major corruption scheme to bring around the Québécois elites. They also imposed a law blocking even further the right of self-determination (the so-called ‘Clarity Act’ of 2000), which was supported by the NDP. In 2011, Jack Layton tried to repair that damage, accepting finally that Quebec had the right to choose its destiny. For a while, the NDP increased its support in Quebec, until, after the take-over by Tom Mulcair (a former minister in the Quebec Liberal government), it came back to its traditional federalist policies. Outside the NDP, the Canadian labour movement and other civil entities have remained silent on the Quebec question.

In 2012, Quebec was the scene of one of the biggest social upheavals in modern times, with hundreds of thousands of citizens rallying behind the student strike. “Le movement est étudiant, mais la lutte est populaire” and indeed it was. While the battle was about student fees, it confronted explicitly the neoliberal policies of merchandizing education and public services, destroying the environment and manipulating governance through a corrupt system established since the 1867 swindle. After the end of the strike, the PQ came back (shortly) in power and the left-independantist Québec Solidaire tripled its popular vote. While the movement caught the attention of some of the left in Canada, it did not generate massive support.

In Lieu of a Conclusion

The split between the Québécois and the Canadian left has never been, on both sides, empowering. At the primary level of coordinating struggles, popular movements have gone their separate ways. At the political level, the distinct objectives and methods were unable to build convergences, which would have required a clear rupture with the Canadian state and much more than rhetorical support to Québécois rights. This mutual weakening was the result of a ‘non-dialogue’ that had started in the early phase of the left, as we have seen before. This situation inherited an historical construct whereas the Canadian left, by and large, did not break with the Engelsian tradition and fell into the trap of the centralized state which would lead the unified ‘nation’ to progress and prosperity.

Again and again, a recurrent argument on the Canadian left is that Québec national aspirations cannot be totally supported because they are not ‘enough’ left. Some would say that Québécois and Canadian are equally despondent in front of the First Nations demands, so that the battle of Quebec is, at the end of the day, between equally repulsive settler projects, which is not the battleground of the left.

“Today, this multitude has decided, wisely, to link up social and national emancipation, breaking up with the old traditions, and fighting very hard for an independence and socialism.”

For sure, this scepticism is founded, but at the same time, it is not legitimate. Canadians will not ‘save’ Quebec from a rightist independence (which is not an impossibility), no more than the British Chartists (and later Labourites) could ‘save’ Ireland. Nor the French socialists could ‘civilize’, ‘modernize’ and ‘socialize’ the Algerians. Today, the Spanish State, even if it turns to the left, will not resolve the internal contradictions in Catalonia or the Basque country because Catalans and Basques have to do it themselves. In Quebec. A turn toward the left, which is not unthinkable, depends on the Quebec social and progressive movements, no one else. Today, this multitude has decided, wisely, to link up social and national emancipation, breaking up with the old traditions, and fighting very hard for an independence and socialism. Is victory ‘inevitable’? Certainly not! If this struggle goes ahead, the Canadian elites, the ‘dispositif’ of power, will be very much weakened and this is why they defend strongly the Canadian state. And so, Quebec’s independence would open new possibilities for the Canadian left.

In the very recent period, a small network of activists from Quebec, Ontario, British Columbia, Manitoba and Nova Scotia have reinitiated the dialogue. [Ed.: see Bullet No. 1368: “Mapping the Canadian Left.”] The point is to agree on a set of principles and benchmarks. It was illustrated publicly by various encounters during the People’s Social Forum in Ottawa in 2015. Québécois and Canadian organizations joined with First Nations to decipher that immoral and conservative entity called the Canadian State. There is a long way to go. The Canadian state cannot be reformed superficially, it has to be reinvented. If it is, the Quebec nation, as well as the First Nations, will be free and will decide how to cooperate with the other nations of the land. It might even be that a new entity reappears, creating a ‘new deal’ between different nations. Before we get there (!), all people at least have to fight together. •