A Response to Murnighan’s “Unifor and Big Three Bargaining”

Deep economic crises, as opposed to the regular ups and downs of capitalism, have played a special role in the history of autoworkers. Since the auto industry emerged as a mass production industry about 100 years ago, there’ve been three such economic crises and each, in different ways, both threatened and tested workers. The first was the Great Depression. In spite of the economic conditions, autoworkers found the courage and creativity to confront the largest corporations in the world and gave birth to the United Auto Workers (UAW). The second crisis occurred in the 1970s and was followed by a concerted assault by governments and corporations on the gains made by the working class since the 1930s. That attack, dubbed ‘neoliberalism’, had a devastating impact on unions. Yet in auto, the refusal of the Canadians to accept the concessionary pattern coming from its U.S. parent led to a break and the formation of a newly energized and confident Canadian union, the Canadian Auto Workers (CAW).

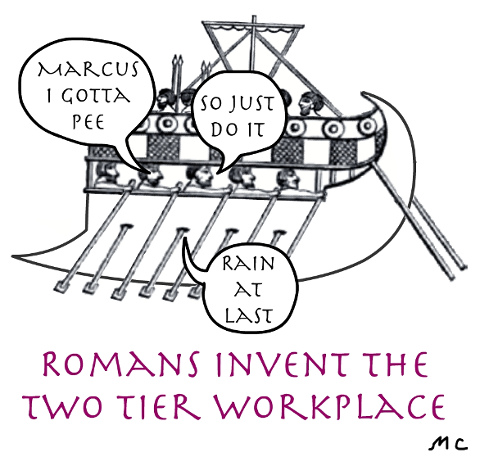

The latest economic crisis pushed GM and Chrysler into bankruptcy. The companies were only saved by massive bailouts from the U.S. and Canadian governments and they used the crisis to further a radical restructuring of pay and pensions. In Canada, wages have been frozen for a near decade, cost-of-living clauses suspended, the union accepted a two-tier wage structure that defied its most basic principles, and a process was started of gradually (immediately for some) phasing out the union’s long standing defined benefit pension plan.

The latest economic crisis pushed GM and Chrysler into bankruptcy. The companies were only saved by massive bailouts from the U.S. and Canadian governments and they used the crisis to further a radical restructuring of pay and pensions. In Canada, wages have been frozen for a near decade, cost-of-living clauses suspended, the union accepted a two-tier wage structure that defied its most basic principles, and a process was started of gradually (immediately for some) phasing out the union’s long standing defined benefit pension plan.

Big Three Bargaining in 2016

With the industry back to accumulating impressive profits, the question as Unifor entered 2016 ‘Big Three’ bargaining was whether the union would signal a clear turning point and fight to reverse those losses. If that were to occur, it would appreciably reinforce other struggles to renew the labour movement.

Alongside the question of how the union would respond in its first bargaining round since the auto recovery lay another, larger but less defined issue. The promises made by elites in response to the crisis of the 1970s – that free trade, globalization, deregulation, privatization and the acceptance of greater inequality would ultimately enrich workers’ lives – were growing thin well before the financial crisis hit. But the crisis served as a catalyst for a hazy but undeniably pervasive undercurrent of frustration and growing anger. Unions cannot ignore this and how they read this mood and respond to it will determine their future role as a social force.

No social institution – not governments or corporations, not political parties or even unions – are today immune from a feeling that they are out of touch with their constituencies and have let them down. In a different era, a sullen biker played by Marlon Brando is asked what he’s rebelling against. He answers: ‘What you got?’ This alienated mood served as an additional backdrop to the significance of Unifor’s 2016 bargaining round. Would Unifor give voice to that general malaise in society? Could the union once again lead in inspiring others?

That undercurrent of rebellion has been particularly expressed on the larger political stage with totally unexpected challenges to the status quo from both the left and the right. It came in the form of Bernie Sanders placing corporate power, class inequality and the shrinking of democracy on the political agenda and the Trump challenge to the Republican Party’s elite. It included Jeremy Corbyn giving the hierarchy of the British Labour Party nightmares because a socialist proud to defend the working class had actually become leader of the party, and it was expressed in the surprise vote in Britain to leave the European Union. But it also surfaced in the 2015 round of bargaining in the USA.

A taste of the rebellious temper of the times emerged in last year’s UAW bargaining with the Detroit Three. The union leadership was aware of the undercurrent against permanent two-tiers but not of the depth of the anger. The UAW negotiated an end to that structure and moved to the Canadian 10-year grow-in. To the great surprise of national and local leaders, rather than being hailed as heroes, they witnessed Chrysler workers doing what hasn’t happened in three decades – they rejected the agreement and they did so by a 2-1 margin. The message was clear: 10 years was still two-tier in their minds. Even after the grow-in was reduced to 8 years and both the union and the company did everything they could do to cajole or scare workers into being more compliant, the Ford ratification only managed to squeak by with a 51.4% majority.

Jerry Dias, the president of Unifor, was reported to have said that his union “has studied the UAW’s experience closely and won’t repeat its mistakes.” He stated, “We saw what happened… We’ve learned our lessons” (Financial Post, Aug 12, 2016). It might have seemed that the ‘lessons’ from the U.S. as well as the broader signs of social unease were tailor made for a bold move on the part of Unifor. Here was the opportunity of a generation for the union to live up to its traditions and give voice and focus to the growing but still diffuse alienation and anger.

Unifor’s New Pattern

This gets us to Bill Murnighan’s defense of Unifor’s new pattern at GM and FCA (Fiat-Chrysler). He begins by declaring that, by definition, there really is no two-tier structure in the pattern agreement. Moving to parity over 11 years is just another expression of the principle of ‘seniority’ and in any case, as people move through the grid they will get ‘significant’ annual increases. He decries referencing the present and recent past agreements as ‘concessionary’ since the frozen wages are not really quite that because they have been compensated – not entirely, but to an extent worth emphasizing – by lump sums. The loss of the defined pension benefit for existing and future new hires is unfortunate but it was inevitable and so not worthy of real resistance. The union, he claims, far from giving in to the corporations, used its collective bargaining power to directly challenge corporate power. And above all, the members have spoken. GM and FCA workers have ratified what the national and local leaders negotiated, and anyone who challenges this is simply showing contempt for workers.

Murnighan is quite right to say that the Canadians do not have a permanent two-tier system since workers do eventually reach full parity. But to the workers on the line, doing the same work and doing it as competently as the person beside them (which normally takes a matter of months, not years) merits getting the same pay. Not getting it until the end of 11 years (almost half and at least a third of what has normally been taken in the industry as the expected life-time of a worker in an auto plant) is effectively a two-tier structure. It’s clear to workers that some of them are treated as second class citizens whatever the technical definition of ‘two-tier’ may be. To claim now that this is no more than an expression of seniority doesn’t explain why the union, backed by its members, has always resisted this structure and only adopted it under extreme pressure, and now is defending it as a collective bargaining victory and norm.

When, in 2015, the U.S. Chrysler workers rejected the 10 year ‘Canadian’ grow-in as a satisfactory alternative to a permanent two-tier structure, they were quite clearly – and articulately – saying that they didn’t consider this an end to two-tier. (The discrimination flowed into benefits such as the short-week benefit with ‘traditional’ workers but not new hires getting compensated when, for example, operations were shut down for brief periods of time because of a parts shortage). That feeling of being second class citizens in the workplace, of unjustified inequality within a union contract, is all the more reinforced when we add in the fact of the permanent two-tier pension system the new pattern put in place (an aspect of two-tiers Murnighan basically ignores).

Trying to lower worker expectations, trying to convince them this is the new normal, hardly seems to be the role of the union, especially a union with any pretensions of leading the movement. And in any case, it won’t work. Workers see it for what it is. And insofar as the new generation of workers – who would have to be the ones to take the lead in a process of union renewal – experience the union itself as a barrier to solidarity, this raises especially hard questions about how to turn things around.

Murnighan points to the fact that the first years of the grid are no longer frozen at 60% for three years. This is of course welcome yet it is understandably hard for workers to feel gratitude for a shameful aspect of the grow-in that had only added insult to injury (as a standard of comparison, the structure in place in the period 1984-2007 got them to 100% within 18 months). As for the significant increases workers get as they move from 61.25% of the base rate in force at the time of hire to its full application after the 10th year and then catch up to interim increases in the 11th year, here as well the point is technically true but more than a little misleading. Aside from the fact that had the starting rate been even lower, the increases would have been still higher, what workers understand full well is that alongside such increases lie the very substantial losses the denial of equal pay has meant up to that point and after.

In making the union’s case in this regard, Murnighan cites the example of someone with 2 years of seniority immediately getting an 11% increase relative to the old agreement followed by increases of 8%, 6% and 5% through this four-year agreement. What he skips over is that these workers, who have already demonstrated they are fully competent at their job, will be paid $11.73 less than the ‘traditional’ worker beside them in that first year ($24,000 annually) and by the agreement’s end the hourly difference will still be $8.51 (almost $18,000 annually). Murnighan considers it ‘ludicrous’ to suggest a loss over the grow-in period of some $200,000, but in his 4-year example alone, the loss is over $85,000. (For those interested, the table at the end tracks the loss relative to the 1984-2007 standard of 85% over 18 months. It shows a loss of $172,000 in direct wages. With roll-up – the impact on overtime pay, sick pay, vacations, pay for downtime, insurances, and with a contributory pension plan that is lowered by the grow-in – the loss would exceed $200,000.)

It’s worth noting, in response to the union accepting corporate limits on what is possible, that going into the 2015 U.S. negotiations, Ford was “the most vocal of the Detroit 3 about the need to keep the [permanent] two-tier pay scale” (Automotive News, May 8, 2016). Yet, when the union moved to a 10-year grow-in and the Chrysler membership pushed this to 8 years, Joe Hinrichs, Ford’s President of the Americas, not only came on side but praised the change: “while dropping the two-tier system increased labor costs, it eliminated a major source of anxiety in the plants, helping workers focus more on their jobs rather than their colleagues’ paychecks.” He went on:

“One of the great things coming out of the new contract has been that we no longer talk about the differences between an ‘entry-level worker’ and a ‘legacy worker.’ All the workers are the same, [and]… that’s really good, because one of the things you really need in a manufacturing plant is there to be focus and discipline. Anxiety or distraction is the enemy of process discipline.”

Fiat-Chrysler’s head, Sergio Marchionne, went even further. Even before bargaining began, he asserted: “There can’t be two classes for people who do the same work… It’s impossible. It’s almost offensive” (Bloomberg, Jan 12, 2015). Marchionne was of course looking for the kind of equality that lowered the wages of all workers. But there was ammo here that the union, with its declarations that the companies are unmovable, shied away from.

It is true, as Murnighan says, that though wages have been frozen and cost-of-living has been suspended for close to a decade, the workers have received lump-sums as partial compensation. But the union had, until recently, done an excellent job teaching workers not to be bought in by the sham of lump-sum payments which, unlike wages, need to be constantly renegotiated to retain the same income level (Murnighan himself did a yeoman’s job in this educational work in his early days in the union). As for the 2% the union got in each of the first and third years, with the once untouchable cost-of-living clause now dormant, this will more than likely keep wages lagging inflation.

Pensions: Complexity and Retreat

As for pensions, yes, this is a complex and difficult issue, as was readily acknowledged in the article Murnighan is responding to. But to deny that the retreat in the previous agreement from a defined benefit pension plan, and now consolidated in this agreement, is a major defeat for the union is quite remarkable. The companies not only got the contributory plan they’ve been asking for, with its shift of risks from the companies to the workers, but in the process it also seems that the companies have drastically reduced the monthly contributions, giving the companies a major windfall. (Estimates vary and the union seems to have stayed away from releasing such costs to the members, but one reliable source puts the company cost of pensions for the traditional workforce at close to 15% of their wage while the corporate contribution to the contributory plan is a maximum of 6% – less than half the cost of the defined benefit plan – with another 5% paid by the individual worker.)

Many traditional workers may feel relieved that they have maintained their defined benefit plan, but some serious concerns should be registered. If past trends teach anything it is that having gone so far, the companies may find it very tempting to later converge their pension – move those on the defined benefits to a hybrid and then to a contributory plan (or to a ‘targeted’ plan, which means that if returns are disappointing, the companies can lower the payouts). Nor should workers rely on governments to protect them; the same governments that give in to corporate subsidies to get jobs may see giving in to corporations on pensions as no different. Most important, ‘traditional’ workers must ask themselves whether – once they have refused to support new hires getting the same pensions they do – they can expect those workers later coming to the defense of only some workers getting the better pension?

Murnighan emphasizes the union commitment to a radically improved Canada Pension Plan (CPP) as the long term answer for providing all Canadians with a secure and adequate pension plan and that is commendable. But voluntarily eroding the pensions of new hires and presenting this as a good deal, not only undermines others trying to hang on to the principal of defined benefit plans but contributes to lowering expectations of what an adequate pension is and reduces pressures on the government to act in a way that results in universal, adequate pensions. (It might be added that from a collective bargaining perspective, it is rather surprising that the union handed GM both this major change, ending pension structures that had been in place since the 1950s, and reconfirmed the 10 year grow-in that even the U.S. had reduced to 8 years.)

Controlling Investment

Murnighan’s sentiment that unions must take on corporate power, especially their unilateral right to determine investment and what happens to communities and families is certainly correct. However, his assertion that the union was using its workplace and bargaining power to challenge corporate power includes no examples of concrete independent union action as the job numbers shrank. When was the last plant occupation? Blockade of transportation? Job action? Strike over production plans? Sustained mass protests locally or at the legislature? (It is also rather difficult to accept that the union will directly challenge corporate control over investment when the union has retreated from taking on ever greater workloads and work pace.) When a challenge to corporations’ exclusive control over investment is not in fact supplemented by direct actions at the workplace, it is pretty clear what making investment commitments the union’s number one and essentially only significant priority implies. The union enters negotiations essentially asking the corporation what it would have to accept to get the investment commitments.

Moreover, addressing control over investment always carries political implications, and this means it must be thought of with an eye to what the implications are for the broader working class, and indeed the society as a whole. In the auto industry it means asking what the industry will look like when new hires finally get to full parity – what will be the impact of the electric car, of driverless cars, of having to deal with the environment – and starting to think now about how we can collectively plan to convert productive facilities and skilled workers that the corporations no longer want to produce the goods we still need and what transforming our society to cope with environmental sanity will require. Addressing what is invested, where and when implies taking on what is wrong with free trade agreements as a priority today, and must always be presented as part of a more general drive to regulate corporations and have some democratic input into what private investors can and cannot do to our jobs and communities. We can’t treat the Prime Minister as ‘a friend of labour’ even as he signs another free trade agreement that makes it even harder to gain any democratic control over corporate investments.

Conclusion: Taking on the Fight

No-one denies how difficult things are today for all workers and their unions, including the autoworkers. The focus on auto is not meant to suggest that only Unifor merits criticism; the crisis in the labour movement runs wide and deep. The issue rather is twofold. First, what this collective agreement represents takes the union down a dead-end street. Notions that ‘we will fix’ things next time are absurd; in four years from now, there will again be threats of job losses if workers raise their expectations. And if the union is back to fighting to ‘get investment’ as its number one priority, other demands will again be cast aside. Second, this road places the union on the terrain of trying to define defeats as victories, defending the indefensible, making arguments that sound uncomfortably close to what the corporations argue. The union is pulled into containing and lowering worker expectations; justifying unjust wage grids; giving lump sums a status they should not have; scaring leaders who reject the direction; and so on. Workers see this and begin to wonder which side their union is on.

Finally, yes, the members voted for this agreement at GM and FCA and this can’t be ignored. But Bill Murnighan certainly knows very well the pressures workers are on from governments, the media and the corporations to give in, to ‘be reasonable’ and how much more difficult it is to make the fight when the union itself takes the same line and when workers know the union isn’t wanting to go into battle or preparing for it. The real news about the ratification votes isn’t that GM workers ratified, but that they ratified by the lowest margins in history, that the same seems true of FCA, that the CAMI leadership publically criticized the agreement. Insofar as the Oakville Local and its leadership have so far stood against the pattern they are clearly reflecting the views of a very many auto workers in the other plants as well as their own. At the time of writing, with GM and FCA in the barn the Ford Oakville Local 707 is the lone nay-sayer to the pattern. It will be extremely difficult for a single local to change the course of bargaining. But the Chrysler workers in the U.S. defied tradition, improved the new hire structure, and still got the new investments they hoped for. Should the workers at Oakville Assembly take on this fight, this might be the start of a renewal in Unifor and an optimistic take on the union’s possibilities as it emerges from the first great economic crisis of the 21st century. •

| Progression Pattern |

Progression Historical |

Hourly Difference |

Period | Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | $20.92 | $29.03 | $8.11 | Start | $8,435 |

| 6 mths | $20.92 | $30.74 | $9.82 | 6 mths | $10,211 |

| End Yr. 1 | $21.86 | $32.44 | $10.58 | 6 mths | $11,007 |

| 1.5 yrs | $21.86 | $34.83 | $12.97 | 6 mths | $13,493 |

| 2 yrs | $22.80 | $35.53 | $12.73 | 1 yr | $26,489 |

| 3 yrs | $24.59 | $35.53 | $10.94 | 1 yr | $22,759 |

| 4 yrs | $25.95 | $35.53 | $9.58 | 1 yr | $19,918 |

| 5 yrs | $27.32 | $35.53 | $8.21 | 1 yr | $17,077 |

| 6 yrs | $28.69 | $35.53 | $6.84 | 1 yr | $14,236 |

| 7 yrs | $30.05 | $35.53 | $5.48 | 1 yr | $11,394 |

| 8 yrs | $31.42 | $35.53 | $4.11 | 1 yr | $8,553 |

| 9 yrs | $32.78 | $35.53 | $2.75 | 1 yr | $5,712 |

| 10 yrs | $34.15 | $35.53 | $1.38 | 1 yr | $2,870 |

| 11 yrs | $35.53 | $35.53 | $0.00 | 1 yr | $0 |

| ** Total ** | $172,154 | ||||

| Est. with Rollup | $200,000+ | ||||

| Pattern progression starts at 61.25% of base at time of hire, reaches 72% at end of 4th yr. then rises by 4% each yr. until end of 10th yr. In 11th yr. interim increases are applied (e.g. the 2% from each of yrs. 2 and 4). | |||||

| Historical autoworker new hire (1984-2008) started at 85% rising 5% every 6 months and reaching 100% in 18 months. | |||||

| Annual hours used here are 2080 (1040 for 6 month calculations). | |||||

| Total difference is over $160,000. With roll-up costs – vacation pay, sick pay, overtime, impact on insurances, SUB, pensions, etc. – total is over $200,000. | |||||

We encourage autoworkers and other members of Unifor – and anyone from other sections of the labour movement – to enter this debate with their thoughts, criticisms, and challenges. To send messages of support go to the Ford Oakville Assembly Plant Facebook page.