Paul Kellogg interviewed by Robin Chang on Escape from the Staples Trap

A concrete understanding of contemporary Canadian economic development depends in part on a grasp of the current institutional structures within the North American economic bloc and how this regional trading bloc interacts with others within the world market. In terms of tracing the history of capitalism in the Canadian context, the next question becomes what are the comparative forms of colonization within the Americas as well as the role of staples commodity exports in that development. Due to these different historical roots, capitalist development has in fact taken different forms, in which varied patterns are persistent through the competitive dynamic of capitalism.

For Canada’s particular economic history, this has often meant studying how natural resource extraction affected the trajectory of capitalist accumulation, and the related formation of class structure and differentiation in the country. The important role of resources sectors to Canadian development, and Canada’s proximity to and relation with the USA trade and investment, formed the context in which the staples theory of growth developed and became accepted among Canadian academics and policy makers. The staples-related economic policy issues and their related academic debates produced an intellectual environment that allowed institutionalism, in addition to radical and Marxist perspectives, to share the political and intellectual stage. During the 1970s, a New Left with a Left nationalist critique of Canadian “dependency,” and a connected political movement centered within the New Democratic Party (NDP), concluded that national sovereignty in the world economy ought to be the priority for the Left.

However, dissidents from the Marxist tradition in the “New Canadian Political Economy” argued against staples theory. As an alternative, they articulated a class analysis of Canadian advanced capitalism in terms of the new “state theories” associated with New Left radicals Ralph Miliband and Nicos Poulantzas. These Marxists argued against many of the themes of staples theory and its explanatory limits, which for them implied that political economy must emphasize and begin methodologically with the social relations of production. Upon this basis, the nature of the staple and the technologies of extraction can then be understood free of the distortions of Staples theory and lead to a proper understanding of Canadian economic development, and class and state formation.

Other Marxists have added that class analysis, while key, is one side of the reproduction of capitalism. The other involves the dynamics of capital accumulation, which structures the economic development of society and determines its dominant mode of production. In capitalism, the separation of producers from means of subsistence under the rule of private

property produces the law of value as an emergent property, where profits drive economic growth, and thereby the reproduction of society.

Paul Kellogg’s Escape from the Staple Trap: Canadian Political Economy after Left Nationalism (2015b) is an ambitious book that offers the first of a two-volume history of

Canadian political economy from a perspective that is highly critical of the staples tradition. It makes a Marxist critique of the empirical cogency of the staples account of Canada’s position in the world market, the class nature of the Canadian social order, and the political implications of the analysis for the Left.

Paul Kellogg is an Associate Professor in the Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies, Master of Arts Integrated Studies Program, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at Athabasca University.

Robin Chang is in the Department of Political Science at York University, where he studies Marxian political economy and is writing his dissertation on the political economy of health and healthcare in Canada and the United States.

Debating Staples and Capitalism

Robin Chang (RC): There are many articles on staples theory and the staples tradition

written from critical political economy and Marxist perspectives. Could you, first of all, give a brief definition of what is staples theory, who created it, and how it has influenced Canadian political economy and economic policy? And what does your book seek to add to this debate?

Paul Kellogg (PK): In the world as a whole, the concept of a “staple trap” has been extremely important for conceptualizing developmental dead-ends in sections of the Global South. Think of Ethiopia and coffee, Bolivia and tin, Cuba and sugar, Jamaica and bauxite. These are some of the classic examples where very poor countries had a staple commodity, could raise money through exporting that commodity, but had an extremely difficult time diversifying away from dependence on that

Paul Kellogg (PK): In the world as a whole, the concept of a “staple trap” has been extremely important for conceptualizing developmental dead-ends in sections of the Global South. Think of Ethiopia and coffee, Bolivia and tin, Cuba and sugar, Jamaica and bauxite. These are some of the classic examples where very poor countries had a staple commodity, could raise money through exporting that commodity, but had an extremely difficult time diversifying away from dependence on that

commodity. The United Nations uses the term “commodity dependence,” defining this as occurring when the value of commodity exports “exceeds 60 per cent of the country’s merchandise export value.” Ninety-four countries fit this profile in 2012-2013, up from 88 in 2009-2010, of which, “45 were in Africa, 20 in Latin America and the Caribbean, 19 in Asia and 10 in Oceania” (UNCTAD, 2015, p. 15).

The concept of unequal exchange is important here. The price for the commodity on which these countries depended tended to stagnate or decline, while the price for the imports needed as inputs into industrialization tended to increase. The countries were caught in a “staple trap.” Understanding this developmental problem was very important for left currents in the 1960s and 1970s, allowing for a conceptualization of the way in which imperialism and Global North dominance could maintain the oppression of whole swathes of the world, even with the winding down of direct colonial rule. Most closely identified with this approach, were Andre Gunder Frank and

the dependency / underdevelopment school (Frank, 1979); and Immanuel Wallerstein and the World Systems Theory (WST) school (Wallerstein, 1974). The political conclusion both drew from this economic analysis was that nationalist resistance to imperialism would lead to the struggle for socialism.

This entered the Canadian discourse through various routes. Intellectually, the figure of Harold Innis is central. Innis theorized that resource staples – fur, fish and feathers – determined a particular path for the development of the Canadian economy (Innis, 1962). Interest in Innis developed simultaneously with the enormous radicalization of the 1960s and 1970s. That radicalization had a very large anti-imperialist component to it, informed by versions of the political economy outlined above, along with – because of the horrors of the Vietnam war – a particular focus on U.S. imperialism. This then intersected with an emerging concern about U.S. ownership of large sections of the Canadian economy. Through the scholarship and activism of Mel Watkins, Kari Polanyi Levitt, Gary Teeple, and others, a left-nationalist dependency school of thought came to dominate the left, crystallizing in the political formation called the Waffle – first within, then briefly outside the NDP. The sharpest formulations of this left-nationalist dependency school were contained in Levitt’s (1970) Silent Surrender: The Multinational Corporation in Canada, and the very influential collection (Canada) Ltd.: the political economy of dependency edited by Robert Laxer (1973). It is the latter that most forcefully argued for a linking of the nationalist with the socialist struggle.

But of course, the context in Canada is quite different from the peripheral economies that were the focus of both the dependency and WST schools of thought. Canada was then and is today an advanced capitalist economy, and nationalism in such an economy is not the preserve of the left. The concern about high levels of U.S. ownership of the Canadian economy did not originate in the left, but rather in the Conservative administration of John Diefenbaker. It was under his watch, that the mechanisms were put in place to more thoroughly track levels of U.S. ownership of the Canadian economy. Further, it was not just the social-democratic NDP that incubated left-nationalism. The Liberal Party of Canada – the traditional governing party of the Canadian elite – played a very large role in this process. Most centrally, Walter Gordon, Minister of Finance from 1963 to 1965, was instrumental in helping to shape the left-nationalist worldview.

In the years since, there have been many critiques of this dependency and left-nationalist approach. A perspective helpful in conceptualizing oppressed nations of the Global South was less helpful when applied to a member nation of the G7. In the anti-globalization movement at the turn of the century, a left-nationalist framing of a country that headquartered Barrick Gold, Magna International and Bombardier, seemed archaic.

Many of the critiques of left-nationalism, however, let slip in through the back door its core assumptions. For instance, an important attempt at reframing Canadian Political Economy this century deployed World Systems Theory in order to conceptualize Canada as a “semi-periphery” – stuck between the core countries of the world economy – the U.S., Germany, and others – and the exploited periphery (Clarkson & Cohen, 2004). The second chapter of the book challenges this and documents that without question, Canada has to be conceptualized as part of the core of the World System. Perhaps Greece, Portugal, Mexico and Venezuela can be conceptualized as semi-peripheries. It is not credible to put a country such as Canada in the same category.

One of the key concepts deployed to critique Waffle-era political economy was the concept “Rich Dependency” (Panitch, 1981). Canada was a “rich” country – one of the richest in the world. But it had developed this wealth in the context of dependent development, ceding elite control to corporations in the United States. This is, however, unsatisfying. The whole point of the dependency school was to develop a framework to explain underdevelopment. Canada – in capitalist terms – is one of the most developed countries in the world. Further, the implication of the rich dependency framework is that while Canada is not underdeveloped now, its structures of dependency will ensure that it becomes so in the future. But the 1980s have been displaced by the 1990s and now by the 21st century, and Canada remains at the core of the world system, an advanced capitalism sharing with a handful of other economies a position at the top of the hierarchy of the world economy.

It is not sufficient to notice that an economy such as Canada exports staples. The question must be asked “what kind of economy”? If this export of staples is organized in an economy with a high level of productivity – in historical materialist terms, with a high and rising organic composition of capital – then the fact of a heavy reliance on export staples will have very different ramifications than in an economy with a low level of productivity – a low organic composition of capital (See Chase-Dunn, 1998, p. 207; McNally, 1981). This is, I think, the central point. Capital is indifferent as to the use-value of the commodities labour produces. It is exchange value that takes centre stage, and the accumulation of capital makes this possible.

RC: The extractive sector continues to be a substantial percentage of Canadian trade. It is particularly key to the economics of First Nations, as well as particular provinces like Alberta. For an alternative to staples theory led research into the extractive sector, do you think that with respect to scholarly literature that comparative colonization studies can provide an adequate explanation for the development of the different economic zones in the Americas at least into the mid-19th century?

PK: If by this you mean integrating into a class analysis the central role played by settler-colonialism, then I strongly agree. Canada is a capitalist economy with a capitalist state. Understanding the class exploitation and class struggle dynamics of that economy and state remain fundamental tasks. But it is a capitalist state shaped by a long and violent history of settler-colonialism. The release of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015) makes this abundantly clear.

While Canada is one of the most developed capitalist economies in the world, this development is distributed extremely unevenly. There are pockets of intense poverty. A class framework allows some of these pockets to come into focus. An anti-colonial framework allows for even greater clarity. I grew up in Cornwall, Ontario. Class and exploitation were visible in the pulp and paper, rayon and other mills that surrounded the town. A class framework brought the poverty of the waterfront area into focus. But to fully understand the depth of inequality in the area, you have to also bring into focus Cornwall’s neighbour, Akwesasne – and that demands an anti-colonial framework.

Look what happens when we struggle to see capitalism with anti-colonial eyes. H. Clare Pentland (1981), for instance, makes a powerful case that the bedrock upon which Ontario industrialization was built, was the market-oriented wheat farming which developed in the years following the arrival of the United Empire Loyalists. But on whose land were those wheat fields planted? Labour and capital are necessary to accumulation. So is land, a point impressed upon me through long and fruitful discussions with Abbie Bakan. The TRC report highlights the way in which the acquisition of land and the establishment of capitalist sovereignty were accomplished through racism and violence.

Comparative colonization studies enhance our ability to engage in comparative capitalist studies. While what is today Ontario developed productive agriculture in the 19th century, what is today Quebec had a much more difficult time – experiencing famine in the 1830s, witnessing population flight throughout the century, tens of thousands abandoning their homes and fleeing to the United States as economic refugees. My book, building on the work of Pentland and McCallum (1980), argues that Quebec’s difficulties were bound up with the archaic structures of the semi-feudal seigneurial system – preserved well beyond its best-before date by British colonial authorities, more interested in preserving elite rule in Quebec, than in fostering economic and social development.

Development Trajectories

RC: I’d like to ask you about your understanding of capitalism in terms of the Modern debates in Marxist historiography over the agrarian versus urban origins of capitalist development. The major theory you identify as the foundation for the staples interpretation of Canadian society as a “dependency” in the world market is Immanuel Wallerstein’s “world systems theory,” combined with ideas related to Paul Baran. Robert Brenner and Ellen Wood have written a great deal identifying and problematizing the rational choice basis of the “commercialization model” explanation for the origins of capitalism. As a result, there are differences by several hundreds of years over when capitalism can be said to have begun. What is your relationship to Brenner’s critique in your general understanding of capitalism, and relationship to world systems and dependency theory?

PK: This question provides a good segue into some of the key themes I hope to develop in the second volume of the book. I think here again, we are confronted with the importance of using an anti-colonial lens along with class analysis.

Let’s frame the issue this way. No doubt a particular configuration of class relations took hold in England, not necessarily prior to other places in the world, but with deeper roots and greater stability. In that sense, the British story is important. However, a narrow focus just on developments within Britain, imprisons the debate into a narrow binary – agrarian versus urban. Was the British countryside the key? Was the British city the key? I think we will never find the key if we fixate on Britain, whether that be the British countryside or the British city. Capitalism per se emerges with the shift to the cash nexus. That requires, well, cash – in the first instance, gold and silver. In the 16th and 17th century, the vast majority of the cash – the gold and silver – which accumulated in the treasuries of Europe, did not come from the market, but came from the bowels of the earth in Bolivia and Mexico, extracted through the genocidal deployment of forced indigenous labour. I learned about this helping out with Toronto Bolivia Solidarity and teaching at Trent University in the Department of International Development Studies. Potosí in Bolivia with its vast veins of silver and gold, is indispensable to the establishment of the rule of capital.

We think of capitalism as a system of exploited free wage labour. However, without the forced labour in the mines of Bolivia and Mexico, there would have been no flood of gold and silver into the world system, there would have been no cash nexus, there would have been no capitalist world system. You cannot see the origins of capitalism without seeing Potosí. Further, the triangular trade which allowed Europe to cement its position at the centre of the world economy, had at its core not the question of free labour, but of slavery. You can’t see the origins of capitalism without seeing São Jorge da Mina in what is today Ghana – and all the other internment camps on the West African coast. In terms of the way you ask the question, we might say that it is time that the origins of capitalism debates properly engaged with Eric Williams (1961) and Walter Rodney (1974).

RC: Brenner’s account has been argued to fit the Marxian theoretical view that the law of uneven and combined development captures the cross-national differentiation and therefore the historically rooted hierarchy in the world market on the one hand, and the apparently surprising way that formerly underdeveloped nations may develop industrially and commercially very rapidly under certain economic and international political conditions. What is your relationship to the theory of uneven development and can it play a role in an alternative theorization of the world market?

PK: I think what is important here is not a theory of uneven development, but of uneven and combined development. It is the “combined” question that is very important – combining aspects of one era with aspects of the contemporary era. Radhika Desai (2013) has brought this to our attention very clearly in her recent Geopolitical Economy.

Uneven and Combined Development (UCD) as a framework is profound, but needs to be separated from the political question of Permanent Revolution. The two are often seen as essentially connected, and I disagree, a point I made in a recent article in Rethinking Marxism (Kellogg, 2015a). The case of China is an enormous example of Uneven and Combined Development. However, there is no need to notice this UCD story and conclude that what happened in 1949 was Permanent Revolution – the combining of the anti-colonial “bourgeois” revolution with the socialist revolution. The society of the Great Leap Forward famine and the Tiananmen Square massacre does not seem, to me, to represent anything we can recognize as socialist.

However, what 1949 did accomplish was the establishment of effective sovereignty. To be more precise, from the 1940s through to the 1960s – against the resistance of Great Powers centred in Europe, Japan, the United States and Russia – the modern Chinese state was able to establish effective sovereignty. The key was not the socialist revolution, but the anti-colonial revolution. I think we have underestimated the importance of anti-colonial sovereignty movements as indispensable in providing political and state frameworks in which economic development can take place. With this modification, then, I find the UCD framework compelling.

Imperialism and Militarism

RC: I’d like to ask you about your understanding of the world market in terms of debates in radical political economy over imperialism. Your

book contains a theory of “military parasitism,” which argues that Canada is an advanced capitalist nation that has a “silent partnership” with U.S. imperialism whose military contracts benefit Canadian capital accumulation. The 1970s debates over the “military-industrial complex,” concerned with the contradictions of military spending in “monopoly capitalism,” produced many different theories as a subset within the imperialism debate. Rosa Luxemburg’s is one theorization, which led to modern versions by Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy, James O’Connor, and other political economists.

What is your theoretical understanding of what is the impact of military spending on the accumulation of capital, understanding that capitalism is, according to Marxist political economy, dominated by the profit motive?

PK: Again, this takes us into terrain central to the second volume. The profit motive is central to capitalism, but we have to say more than this. Profits can be acquired through production. They can also be acquired through pillage. The history of capitalism sees both co-existing. Each has its own benefits and costs.

The benefits of pillage are many. Concentrating on the expansion of the means of destruction can allow a state to bypass the more complex developmental steps required in expanding the forces of production. The Vandals and the Vikings were iconic examples of this. So were the absolutist states of late-feudal Europe. The imposition of the Rule of the Cash Nexus (discussed earlier), does not demonstrate the productive superiority of Europe, but rather its destructive superiority. European civilization was in no way more advanced than the American or African or Asian civilizations it encountered. It certainly did not possess a more productive economy. But it was more destructive. Shaped by a millennia of chaos following the fall of the Roman Empire, there developed a horrifying mass tolerance of and capacity for violence. It was this violence which was exported to the rest of the world in the form of European colonialism, laying the basis for the capitalist world economy.

In the 19th century, the British navy and in the modern era, the United States Pentagon, represent the continuation of the pillage aspect of capitalism. A focus on refining the means of destruction, allowed both to experience the many “benefits of empire” – access to markets, propping up of compliant compradors to facilitate the extraction of resource wealth, an ability to deploy a national currency as “world money.” All of these allowed tremendous wealth to flow into the British Isles in the 19th century, and into the U.S. in our era. Like the Vikings and the Vandals, the British and U.S. empires became adept at violently extracting surplus produced elsewhere.

However, there are also costs to empire. Sustaining one half of the world’s destructive power (as the U.S. has for decades) completely distorts U.S. central government finances. Huge portions of the central government’s budget are permanently directed toward the military, resulting in an over-developed warfare state, and an underdeveloped welfare state (Kellogg, 2013). The second volume documents the way in which the maintenance of a welfare state is not simply good ethically. It has positive effects economically, because of the central role played by human capital in a modern economy.

Further, the diversion of surplus toward the warfare state, over time, has a profoundly negative impact on the “civilian” economy. The U.S. is a society that proclaims its opposition to all “industrial policies.” But, the privileged role of the Pentagon has in fact created one of the most aggressive state-directed industrial policy regimes ever seen in the history of capitalism. Civilian industries are starved over time, hence the Rust Belt in the Midwest and Northeast. Military industries are privileged and pampered, resulting in the Gun Belt in the south and west (Koistinen, 2012). The economic geography of the United States is a twisted and dysfunctional product of an addiction to war.

This is unsustainable in the long run. Over time, the question of productive capacity is more important than the question of destructive capacity. One consequence of sustaining a permanent war economy, has been the long-term secular decline since the end of the Second World War of the place of the United States in the world economy, and this decline continues in the 21st century. Its economy is, of course, absolutely bigger than it has ever been. But its relative position, by all measures, has declined and continues to do so. The George W. Bush administration gathered around itself the PNAC (Project for a New American Century) group of intellectuals who argued that this economic decline could be compensated for and offset by an aggressive assertion of military power (New Citizenship Project, 2006). The resulting fiascos in Iraq and Afghanistan did not simply fail militarily, politically, and ethically, they laid the groundwork for the Great Recession of 2008-2009, accelerating rather than reversing the relative decline of the U.S. I am well aware that there are many who dispute this position (Panitch & Gindin, 2012), but in my opinion the evidence for this decline is overwhelming.

Canada’s relationship to this has been complex. Military parasitism has allowed Canadian capital to participate in the exploitation of sections of the world “kept safe” for capitalism by U.S. empire (the Caribbean being a classic example) while avoiding the overhead costs of empire. The benefits accruing to Canadian banking, mining and other capitalists have been substantial. However, the military parasite approach also involves exporting into the arms producing sector of the United States (or military client states of the U.S. such as Saudi Arabia). This makes Canadian capitalism quite vulnerable to the restructuring North America will confront should the maintenance of a massive arms economy become too costly for the U.S. elite.

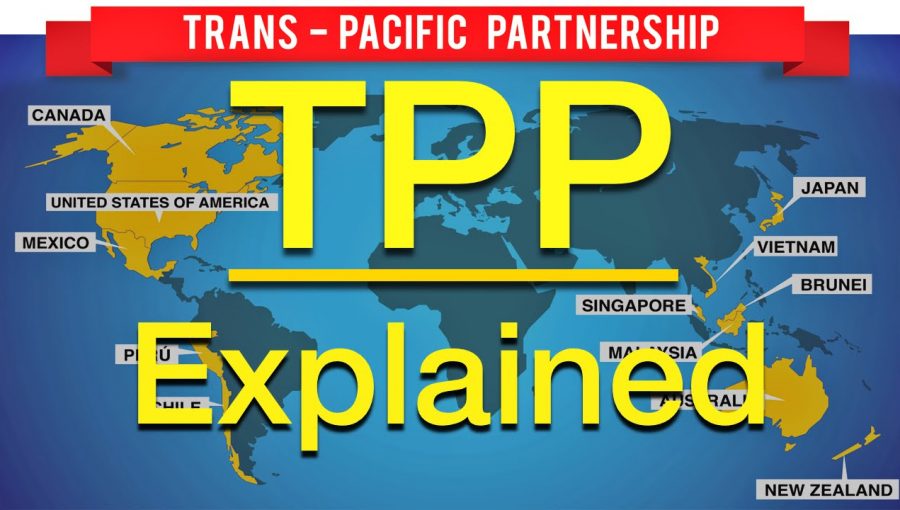

RC: I’d like to ask you a question in theoretical terms about how the Left does and should relate politically to trade agreements such as the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and this year’s Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the ways that neoliberal policy

thinking and the power of the capitalist power is extended. The theory of imperialism is key to locating Canada or any nation in the world market. I was wondering what is your relationship to Nikolai Bukharin’s theory of the internationalization and nationalization of capital in the Canadian context. This theorization is famous for concluding that capitalist competition increases interdependence between actors in the world economy on the one hand, and at the same time divides the world market into regional blocs. How should the Left understand and relate politically to neoliberal projects such as TPP in contemporary North American politics?

PK: The English translation of the title of Bukharin’s book is Imperialism and World Economy (1915a). It really should be World Economy and Imperialism (Bukharin, 1915b). The difference is not trivial. The central importance of Bukharin is not associated with his theory of imperialism, but his insistence on taking a world economy approach to all national economic questions. It is in this sense that I think Bukharin is an important thinker.

His framework does help us understand the push for blocs of capital such as NAFTA and the TPP. Increasingly, national economies are too small on their own to compete effectively in the world market, and there is a tendency toward regionalization. This helps us understand what NAFTA and the TPP are – moves toward regionalization and cartelization of corporate control – and on that basis we have to oppose them.

However, all sorts of dangers immediately emerge. The most readily available epistemologies to deploy in the face of either NAFTA or the TPP or the EU are various versions of nationalism. Again and again, this has resulted in the left keeping strange company. In Canada, the left nationalists made common cause with the Liberal Party in the campaign against Free Trade. It was, of course, the Liberal Party which, when in office, implemented NAFTA. In Britain in the campaign against the EU, George Galloway has shared a platform with Nigel Farage. And in North America, the most vocal critic of trade deals in the current moment, is none other than Donald Trump.

I think we have to pause here and learn lessons from history and from the Global South. From history, we should study Leon Trotsky’s notion of a socialist “United States of Europe” (Trotsky, 1923). Lenin had historically opposed the idea (1915). I think Trotsky was correct, and Lenin wrong. Trotsky was indicating the way in which the left has to acknowledge the limitations of a strictly national focus on economic development.

From the Global South, we need to take seriously the noble experiment of ALBA – the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (Kellogg, 2007). This alliance has fallen on hard times, given the austere economic conjuncture being faced by Cuba, Bolivia and Venezuela in particular. However, from its launch in 2005, ALBA articulated a non-nationalist vision of economic development, a solidaristic vision, which has been too little studied in North America. We need to offer a progressive politics of regional solidarity to counter the capitalist politics of regional exploitation.

Conclusions and Openings

RC: The book concludes very clearly that in the Canadian context, social injustice and inequality to do with race, gender, and class have to be understood in terms of a historical materialist conception of capitalism, and with them the revolutionary political implications that follow. Based on your class analysis, I’d like to ask you about the contemporary terrain in Canadian politics. First, how would you identify what are the most important current political interventions and locations in Canadian society the Left ought to pursue as part of a revitalization of the Left?

PK: This is a wonderful question, but it does take the discussion quite a ways outside the framework of both books. Here I will only attempt a few very general remarks.

The left needs to seriously embrace a non economic-reductionist approach to class. An economic reductionist approach narrows our vision to the workplace and trade union organization. Given the low level of strike activity and the erosion of unionization rates, this can lead to a profound pessimism. But the answer to that pessimism is being provided outside the traditional structures of the workers’ movement – in Idle No More, in the Climate Justice movement, in Black Lives Matter, in the rage against the Ghomeshi ruling, in the Quebec student strikes. These are not external to the rebuilding of workers’ resistance, but integral components of it. We know this from past experience. The general strike in France in 1968 would not have happened without the preceding youth/student rebellion. Left sovereigntist resistance to martial law in Quebec in 1970 was the immediate background to the magnificent workers’ uprising in 1972. The Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement (DRUM) represented the high water mark for the U.S. workers’ movement in the 1970s, and DRUM was a direct product of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense.

Building this kind of solidarity across movements also requires building solidarity across borders. This is quite relevant to the analyses of both books. The left-nationalist dependency school, both in its heyday and in the shadow it still casts over political discourse in Canada, tended to displace our focus from the Canadian elite to the U.S. or other “foreign” elites. In the current context, the tar sands problem has often been framed as pitting us against non-Canadian corporations which are directing the exploitation of this resource. I have an article coming out in the Journal of Canadian Studies (Kellogg, 2015c), showing that, in fact, the tar sands are in their majority exploited by Calgary-based Canadian corporations. Larry Pratt and John Richards in Prairie Capitalism (Richards & Pratt, 1979) were prescient in this regard. One side of the politics flowing from this is restrictive – when it comes our struggle for climate justice, just as it was for the anti-war movement in Karl Liebknecht’s time, “the main enemy is at home” (Liebknecht, 1915). The other side is expansive. We have many allies with whom we can link arms across all borders, including the one between Canada and the USA.

RC: What kind of transitional programmatic demands seem most important to build upon in order to relate different groups and perceived interests together to build and expand popular unity?

PK: It would be out of place for me to make specific suggestions. The key demands will emerge organically – and creatively – from the movements themselves. The role that political economy can play here, perhaps, is to indicate the way in which economic demands are intrinsically bound up with political demands. Here, we can profit by bringing into focus the political economy of Rosa Luxemburg (1915). There is a recurring tendency in historical materialism to try and understand capitalism solely through abstract formulae. It can’t be done. You can to some extent conceptualize the market in the abstract. This was the method of Adam Smith, David Ricardo and the classical economists, and in the current day the method of the neoliberals and the monetarists. But the market is not the same as capitalism. The market – as Rosa Luxemburg showed more clearly than any other – can never on its own adequately valorize the products of labour. Capitalism has always married the market to this or that system of violence, forced labour, genocide and war. This is not contingent, but systemic.

So to challenge capitalism economically, we will be up against capitalism politically – against its racism, its drive to war, its refusal to deal with the continuing realities of settler-colonialism, etc. This is not a moral question, but one embedded within the logic of capitalism itself.

Many of the left-nationalist political economists, a critique of whose writings comprises much of Escape from the Staple Trap, were acutely aware of the need for the building of a new, solidaristic left on this basis. In fact, that is what motivated their intellectual labour. The point I try to make is that the theoretical frameworks they established became a barrier to that political project. To get to the solidaristic left we all want, requires theoretical clarity as to what Canada is, and what it is not. My book tries to make a contribution to this discussion. •