For readers immersed in the annals of Empire, it is well known that the United States is no ordinary country in the world system. The United States is a unique Empire whose national security strategy since 1945 has relied upon a mix of diplomacy and brute military force to make the world safe for American capitalism around the world, and more importantly, made the world over forglobal capitalism. Unlike bygone colonial Empires, the U.S. Empire has not in its recent history tried to directly dominate territories, but instead, strove to build, integrate and police a world system of allies that share its model: capitalism, the neoliberal state form, and the consumerist “way of life.”

As of late, though, we read that the U.S. Empire is in relative decline, perhaps even headed toward a full-fledged collapse. The old American Century is supposedly being eclipsed by a new Chinese one. Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (the “BRICS”) are a bloc emerging to challenge the U.S. Empire. A tectonic shift from a U.S.-unipolar order to multi-polar disorder is happening.

As of late, though, we read that the U.S. Empire is in relative decline, perhaps even headed toward a full-fledged collapse. The old American Century is supposedly being eclipsed by a new Chinese one. Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (the “BRICS”) are a bloc emerging to challenge the U.S. Empire. A tectonic shift from a U.S.-unipolar order to multi-polar disorder is happening.

The spectre of decline has haunted the U.S. Empire for as long as scholars and activists have attempted to understand and change it. In 1960, U.S. President John F. Kennedy declared that the “fundamental problem of our time is the critical situation which has been created by the steady erosion of American power relative to that of the Communists in recent years.” But it wasn’t. In the 1970s, deindustrialization, the horrors of Vietnam, the OPEC crisis, and stagflation set off a powder keg of opinion that the U.S. Empire was finished. But it wasn’t.

The rise of West German and Japanese capitalism throughout the 1980s and their taking a bite out of the U.S.’s piece of the global economic pie combined with military over-stretch sparked more chatter about America being in trouble. But it wasn’t. In the 1990s, neoliberal and postmodern proponents of “globalization” argued that the break-up of the Soviet Union, the consolidation of the European Union and new developments in info and communication technologies heralded a fundamentally new world system that was post-U.S. Empire. But it really wasn’t. The Bush Administration’s post-9/11 launch of the global war on terror momentarily revived talk of the U.S. being an Empire, and quite a strong one. But then the Global Slump of 2007 sunk in, and declinism once again spun around the planet.

Whether or not the spectre of decline is now a real material force around the world is up for debate, and fortunately, many democratic socialists have made important and astute contributions to it. Now, early into 2016, we read everyone from the neoconservative hawk Charles Krauthammer lamenting the chaotic conditions of a world system marked by “disarray” due to “American decline” to the former U.S. Ambassador Chas W. Freeman Jr. worrying that if Americans fail to “repair the incivility, dysfunction, and corruption of our politics, we will lose our republic as well as our imperium.” The rhetoric of decline is nothing new, and it is regularly wielded by the U.S. Empire’s opinion-makers to build working class consent for programs to rebuild U.S. power each time elites perceive it to be waning. The imperial messenger Thomas Friedman, for example, teamed up with Council on Foreign Relations member Michael Mandelbaum to make a liberal case for American renewal. And Donald Trump’s conservative narrative of decline fills the heads of his acolytes with dreams of Empire-enabled social mobility by promising to “make America great again.”

The U.S. Empire is indeed currently beset by serious problems as the world system undergoes real and significant changes. Yet, the declinists of our time risk overlooking the solidity of the U.S. Empire’s power relative to would-be contenders, and their flagging of present-day change downplays continuities with the past. For the short term, the U.S. is still the only Empire, and with regard to its combined power – capitalist, military and communications media – it is largely unrivaled.

The U.S. is home to the most (and most of the biggest), trans-national corporations (TNCs). The 2015 Forbes Global 2000 ranks the world’s biggest companies using four metrics (sales, profits, assets and market value). While many countries around the world are home base to various TNCs, the U.S. is still global capitalism’s grand central station. The statistics are staggering. Although the U.S. and China are evenly split when it comes to the top ten largest TNCs, the U.S. is home to 580 TNCs, a sum larger than its next three competitors combined: China (232), Japan (219) and the United Kingdom (104). Together, the BRICS total 341 – Brazil (13), Russia (27), India (56), China (232), and South Africa (13) – a sum that falls short of the U.S. by 239.

Moreover, the U.S. is still the centre of global finance capitalism, as the dollar, not the Yuan or the Euro, is the reserve and most used currency. Central banks, corporations and consumers inside and outside of the U.S. still look to the Federal Reserve to back their holdings. Additionally, Forbes’ 2016 list of the world’s shows the U.S. is very much home to the planet’s combined wealthiest bourgeoisie. 540 billionaires live in the U.S. while 518 live in the BRICS: Brazil (30), Russia (77), India (84), China (320), and South Africa (6). Sixteen of the world’s top twenty-five richest people are American, and these super rich include: Bill Gates (Microsoft), Warren Buffet (Berkshire Hathaway), Jeff Bezos (Amazon.com), Mark Zuckerberg (Facebook), Larry Ellison (Oracle), Michael Bloomberg (Bloomberg LP), Charles Koch (Koch Industries), David Koch (Koch Industries), Larry Page (Google), Sergey Brin (Google), Jim Walton (Wal-Mart), Sheldon Adelson (Casinos), George Soros (Hedge Funds) and Phil Knight (Nike).

Declinists are correct to point out that the U.S.’s share of global nominal gross domestic product (GDP) has been falling for the past fifty years or so, from about 40% in the early 1960s to 24.4% in 2015. But given the U.S. has a mere 4.4% of the world’s population (319 million people on a planet of seven billion), its hold of nearly a quarter of world GDP is outstanding. China, home to about 20% of the world’s population (more than 1.35 billion people), accounts for 15.5% of the global GDP.

The U.S.’s capitalist might is coupled with its continuing military dominance. In 2015, the U.S. was the world’s top military spender. The U.S.’s 2016 defense budget is $596-billion whereas the BRICS account for $368.7-billion. The U.S. defense budget is almost three times the size of China’s ($215-billion), the world’s second largest military spender, almost nine times the size of Russia’s ($66.4-billion), the third biggest spender, and more than eleven times the size of India’s ($51.3-billion), the fourth top spender.

A portion of the U.S. Empire’s gargantuan war chest flows to U.S.-based war corporations, which research, develop, and sell weapons technologies to the Department of Defense (DOD). Six of these rank among the top ten biggest war corporations in the world: Boeing, Lockheed Martin, General Dynamics, Raytheon, Northrop Grumman and Precision Castparts – all major DOD contractors and procurement sources. Unsurprisingly, the U.S. continues to be the world’s biggest exporter of arms.

Over the past fifteen years, the U.S. has pummelled or intervened in Afghanistan, Iraq, Haiti, Venezuela, Guatemala, Libya, and Syria.Moreover, the DOD controls an estimated 7,100 nuclear warheads (compared to China’s 260, Russia’s 7,700, and India’s 120) and maintains almost 1,000 military bases across more than sixty countries, many dutifully propped up with a Status of Forces Agreement signed by host client States. Russia has bases in nine countries (the most recent implant is in Syria) and China is building some floating bases on coral islands in the South China Sea. Clearly, neither Russia nor China come close to rivaling the U.S.’s military base superiority. And there is no country on the planet today engaged like the U.S. in a permanent war with no clear boundaries or foreseeable end in sight.

More recently, the U.S. has carried out hundreds of military actions across Africa and is pivoting its military and diplomatic corps toward East Asia to contain a rising China. The U.S. National Military Strategy of 2015 says Russia, Iran, North Korea and China are “acting in a manner that threatens” the American “national security interest.” Signalling the possibility of a Third World War, it says “the probability of U.S. involvement in interstate war with a major power is assessed to be low, but growing.”

Global peace is not forthcoming.

The immense capitalist and military power of the U.S. Empire is complemented by concentrations of communications technology, media and cultural industry power. The 2015 Forbes Global 2000 list shows nine of the world’s top ten media companies to be based in the U.S.: Comcast, Walt Disney, Twenty-First Century Fox, Time Warner, Time Warner Cable, Directv, CBS, Viacom, and BSky Broadcasting. Moreover, the U.S. is home to five of the top five biggest broadcasters and Cable TV firms (Comcast, Walt Disney, Time Warner, Time Warner Cable, DirecTV); two of the top five communications equipment firms (Cisco Systems and Corning); two of the top five computer hardware firms (Apple and Hewlett-Packard); three of the top five computer service firms (Google, IBM, Facebook); four of the top five computer storage device firms (EMC, Western Digital, SanDisk, NetApp); three of the top five Internet and catalogue retail firms (Amazon.com, eBay, Liberty Interactive); three of the top five publishing companies (Thomson Reuters, Nielsen Holdings, Gannett); two of the top five game firms (Activision-Blizzard and Electronic Arts); two of the top five semiconductor firms (Intel and Qualcom); four of the top five computer software and programming firms (Microsoft, Oracle, VMware, Symantec); and two of the top five telecommunication firms (Verizon Communications and AT&T).

Large and globalizing communications technology, media and cultural industry companies certainly exist in other countries, such as Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, Sweden, and the BRICS. But in almost every industry segment of the Forbes Global 2000, U.S. companies are dominant. All in all, the U.S. is home to 92 of the world’s biggest communication technology, media and cultural industry firms. They are the most significant owners of the world system’s technological infrastructure, the means to service and access this infrastructure, and the lion’s share of the means of producing, distributing and exhibiting the commercialized informational and media goods pulsing through it each day. The BRICS collectively house a mere 25 of the world’s biggest companies in this area, and as a bloc, are far from rivaling the USA.

With regard to its combined structural power, the U.S. Empire is still a substantial force to be reckoned with.

U.S. Empire’s Security for Capital, Insecurity for Workers

The quantifiable reality of the U.S. Empire’s power is an important counterpoint to hard and fast declinism, but the reified image of its power is also used to mask the social class power it perpetuates. So much of the U.S. Empire’s power is rationalized as necessary to secure “America” and much of the world from real and imagined “threats,” with “national security” foregrounding it in an expression of the collective interest – though it clearly does not serve the interests of everyone.

The U.S. Empire is one in which the corporate rich and powerful few preside over the State while the many working people beneath are compelled to sell their labour-power in exchange for a wage they need to survive. It is an Empire in which the State’s national security planning structure is hierarchical, centralized, exclusionary, elitist, and “heavily and consistently influenced by internationally oriented business leaders.” The State’s national security interest largely serves trans-national capitalist interests while masking this fact by depicting what’s good for global corporations as good for “America” and vice versa. The U.S. Empire’s securing of the private profits of the capitalist rich over the social needs of the many has fostered conditions that make workers around the world more insecure. The privileged few atop the U.S.’s social hierarchy influence foreign policy and they are the primary beneficiaries of the Empire’s “security.” The working class majority, excluded from foreign policy decision-making, bears and is made insecure by its costs.

As the U.S. Empire grows, so does inequality between the owning class and the working class. The U.S., home to the most concentrated private wealth on the planet ($63.5-trillion in total), is also the country with the largest wealth inequality gap between the rich and the poor. The .01% of America’s super rich takes in upwards of $25-million a year while more than half of Americans earn under $30,000. CEO-to-worker pay scales vary across industries, but the gap between what CEOs take from workers and what workers make in wages has increased over the past five decades.

In the 1960s, CEOs earned about 24 times the amount of the average worker. In 1980 they got 42 times more. Now they get anywhere from 50 to over 600 times of workers’ pay. As the U.S.’s share of world GDP has gone down, the compensation for American CEOs has gone up, with top CEOs now taking an average more than 300 times the typical waged worker. In 2014, the CEOs of Comcast Walt Disney, News Corporation, Time Warner, CBS and Viacom each pocketed a median compensation of $32.9-million (U.S.). In 2015, Donald Thompson, the CEO of McDonalds, got paid 644 times more than the average McDonalds worker, whose fight for $15 continues to be thwarted.

While the U.S. Empire keeps building up its guns, the State’s low taxes on the rich and squeezing of the working class plus austerity measures has made the provisioning of public goods less of a priority. The U.S. State spent $3 to $7-trillion on wars in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria, killing an estimated 1.3 million civilians in the process and stoking global anti-American blowback. Yet, it doesn’t have the resources or mechanisms in place to feed the 15.3 million American children under the age of 18 currently living in hunger. It allocates hundreds of billions of dollars to the R&D of technologies of death by the likes of Lockheed Martin (e.g., the F-15) while its own infrastructure crumbles and public schools and peaceful routes to a good life get defunded. The public education system’s teachers add more value to society than defense contractors, yet they have joined their students as the precarious poor. Persuaded to see college, not class struggle, as the path out of poverty, many poor racialized people sign up to be sent off to war in exchange for a shot at tuition. Many return home with PTSD and are unable to live, let alone go back to school. In 2014, approximately 22 Afghanistan and Iraq war veterans killed themselves each day. Since 1962, the U.S. State has funnelled more than $100-billion in aid to Israel, yet still can’t find the cash to build public housing for America’s poorest. It bailed out Wall Street with $16.8-trillion, yet can barely fathom a living wage to lessen the immiseration of American workers without coin-operated neoliberal think-tanks lamenting that some billionaire would suffer.

As the U.S. Empire expands, so does class inequality between the propertied few who benefit from ongoing wars waged for the security of capitalism and the millions of workers made insecure by its social consequences.

That said, the U.S. Empire is not spontaneously liked or always pre-approved by American working people, nor by those living across the many allied states that make up its sphere of influence. From its earliest days, the U.S. Empire has been contested by American anti-imperialists. Inside and outside of the U.S., anti-imperialism has a rich, progressive and trans-national history. Since 9/11, many have done the republic a service by calling for the U.S. Empire to be “dismantled.”

Yet, the powerful have fought hard to deter and de-Americanize the democratic tradition of anti-imperialism. As a result, anti-imperialism is not a very popular or pervasive position today. Despite the U.S. Empire’s many perils and sorrows, a large number of Americans still believe they live in the world’s best country. The millions who disagree are being seduced by Trump to “make America great again.” Around the world, global opinion about the U.S. is “mostly positive.”

Given these contradictions, what might compel so many working people to accept this Empire as a “way of life”? Why might working people look so favourably upon the U.S. Empire, no matter how controversial it is? What means do the U.S. Empire’s planners rely upon to make the ruling class interest in neoliberal capitalism and global war appear to be the collective security interest of all?

The U.S. Empire’s Culture Industry: Selling Empire as a Way of Life

During the Second World War, Max Horkheimer and Theodore Adorno coined the concept of the “culture industry” to both highlight the capitalist system’s incorporation of culture into its circuits of accumulation and interrogate the for-profit production, distribution, and marketing of all the world’s cultural forms – high and low – as commodities. For them, cultural commodities seem to help people cope with alienating work routines, conceal the class system through portrayals of America as a land of happy consumers, close minds to the terrible state of present conditions instead of opening them to alternative futures, and teach conformity not critical thinking.

Early into the 21st century, the U.S. culture industry retains global dominance. CNN is the most watched international news source across Africa. Year after year, Hollywood rules the worldwide box office. The top twenty highest grossing films of 2015, from blockbusters like Star Wars: The Force Awakens to Jurassic World, are owned by a few studios in Los Angeles, California. CBS’s NCIS is the world’s most watched show, mobilizing the attention of more than fifty five million viewers spanning over two hundred cultural markets. Call of Duty: Black Ops III, Madden NFL 16, Fallout, Star Wars Battlefront and Grand Theft Auto V are the top five best-selling video games of 2015, all the property of U.S.-based studios. Google, Facebook, YouTube and other U.S. digital giants control the most visited websites in the world. These behemoths of the Internet monitor, mine and then assemble all user-generated content into data profiles, and then sell these precious commodities to advertising firms in an expanding market worth more than $100-billion.

While capitalist logics drive the U.S. culture industry’s growth, the U.S. State has long relied upon this industry’s creative labour-power for global pro-American consent-building, particularly regarding issues of national security and war. Going back to World War I, the U.S. State and the culture industry forged a cozy relationship via the Committee on Public Information (CPI). In How We Advertised America, CPI head George Creel famously declared that the CPI was “a vast enterprise in salesmanship,” and “the world’s greatest adventure in advertising.” From the CPI in World War I, to the Office of the Coordinator for Inter-American Affairs in the late interwar period, to the Office of War Information in World War II, to the United States Information Agency in the Cold War, and to the Office of Public Diplomacy in the U.S. War on Terror, the U.S. State has consistently established links with media firms to promote U.S. Empire to the world.

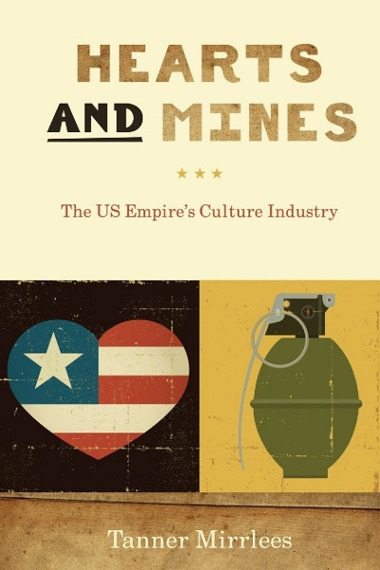

Hearts and Mines: The U.S. Empire’s Culture Industry theorizes and historicizes this contradictory convergence of the interests of the U.S. State and U.S.-based globalizing culture industry. The concept of the U.S. Empire’s culture industry flags a geopolitical-economic nexus of the U.S. State (striving to promote itself and engineer public consent to dominant ideas about America and U.S. foreign policy around the world) and U.S.-based yet globalized media corporations (seeking to make money by producing and selling cultural commodities to consumers in world markets).

Although the national-security interested U.S. State is relatively autonomous from profit-interested media corporations, I show how these two organizations often work together to manufacture and sell commodities that sell Empire as a way of life. The geopolitical interests of the U.S. State and the capitalist goals of U.S. media corporations do not always march in lockstep, and at times they conflict, yet the U.S. Empire’s culture industry points to a more collusive relationship between state agencies and media firms than is often recognized.

Faced with anti-imperialism at home and blowback abroad, the U.S. Empire’s culture industry in the early 21st century is deploying an even larger army of commodities that strives to grip the hearts and minds of American and trans-national publics and keep the U.S. Empire admired – or, at least, tolerated.

In the same year the U.S. Marines enlisted Perry’s pop image to portray military service as a righteous path to women’s liberation, Warner. In 2012, U.S.-based Capitol Records’ teen idol Katy Perry hooked up with the U.S. Marines to make the music video for her hit song “Part of Me.” In this video, Perry catches a cheating boyfriend. Instead of getting angry at him, she gets overtaken by a military recruitment ad that tells her “All Women Are Created Equal, Then Some Become Marines.” To spite her boyfriend and cope with heartbreak, Perry joins the Marines, cuts her hair, camo-paints her face, and endures basic training at the Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton alongside actual U.S. Marines, who dance, sing, and fight to her song. Following “Part of Me,” Perry said shooting the video turned her into a “wannabe Marine” and made her “so educated on people in the service,” whom she sees as “the heart of America.”

In the same year the U.S. Marines enlisted Perry’s pop image to portray military service as a righteous path to women’s liberation, Warner. In 2012, U.S.-based Capitol Records’ teen idol Katy Perry hooked up with the U.S. Marines to make the music video for her hit song “Part of Me.” In this video, Perry catches a cheating boyfriend. Instead of getting angry at him, she gets overtaken by a military recruitment ad that tells her “All Women Are Created Equal, Then Some Become Marines.” To spite her boyfriend and cope with heartbreak, Perry joins the Marines, cuts her hair, camo-paints her face, and endures basic training at the Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton alongside actual U.S. Marines, who dance, sing, and fight to her song. Following “Part of Me,” Perry said shooting the video turned her into a “wannabe Marine” and made her “so educated on people in the service,” whom she sees as “the heart of America.”

Bros. Pictures geared up to release Man of Steel. This blockbuster casts the classic DC Comics character Superman alongside the men and women of Team Edwards Air Force Base. Superman and the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter fly and fight together against alien evil that threatens the planet. “It was a great choice,” said Mark Scoon, an executive at Warner Bros. “Our experience at Edwards has been beyond phenomenal, no matter how you look at it – from the bottom up, or top down. There has been extraordinary cooperation across the board.”

While Man of Steel travelled the globe, taking in $25.8-million from China’s box office in one weekend alone, NBC was broadcasting a reality show called Stars Earn Stripes. Produced by reality TV mogul Mark Burnett and hosted by retired military general Wesley Clark, the show pairs B-list actors with U.S. Navy SEALs, Marines, and Green Berets to complete military training challenges in competitions to win money for various charities. NBC’s website described the show “as an action-packed competition show that pays homage to the men and women who serve in the U.S. Armed Forces and our first-responder services.” In response to criticisms that it cheapened war, U.S. Navy Corpsman Talon Smith candidly quipped: “Entertainment is how America will receive information.”

Yet, in 2012, many people were not just passively receiving infotainment about the military from TV shows. Instead, millions of people were paying to virtually “play kill” as soldiers in the hyperreal wars of digital games. The online game Kuma/War let people play simulated versions of U.S. military events – from killing Osama bin Laden to helping Libyan rebels kill Muammar Gaddafi – soon after the U.S. news packaged them as having happened. The more than seven million copies of Battlefield 4 sold worldwide meanwhile recruited players to virtually fight alongside a U.S. special operations squad across and against a belligerent and threatening China. For facilitating this “cultural invasion” and smearing “China’s image,” China’s actual Ministry of Culture banned the game.

The above are but a few of the hundreds of media commodities packaged and sold by the U.S. Empire’s culture industry to teach working people in the U.S. and around the world to identify with Empire.

The U.S. Empire, to be Continued?

The U.S. is an Empire and the pillars of its structural power – economic, military and communications media – remain entrenched around the globe. Despite the remarkable rise of the BRICS, none of these countries rival the USA. As recent research shows, the BRICS are facilitating and legitimizing their own integration into the neoliberal capitalist circuitry of the U.S. Empire while simultaneously trying to hollow it out.

To promote, glorify and sell the U.S. Empire as a way of life around the world, the culture industry is vital. The U.S. Empire’s culture industry tells U.S. workers they must continue waging wars “over there” so that they do not have to fight “over here” and tells workers around the world that the best dream to have is to become more American.

An internationalist strategy advises U.S. workers to peacefully struggle against the trans-national capitalist elite over “here” in solidarity with democratically minded anti-imperialist workers “everywhere.” Instead of focusing on trying to transform other societies, the U.S. should focus on understanding and changing itself, and for the better. A deeply democratic and socially just republic at home cannot exist alongside an Empire abroad. Until then, democratic socialists face the challenge of dismantling the Empire from within, and they can do so united with progressives around the world. As Robert McChesney puts it, “If a viable pro-democracy, anti-imperialist movement can emerge” in the U.S., “it will improve the possibilities dramatically for socialists and progressives worldwide.” •