A Book Review by Chris Schenk

Continental Crucible, written by Richard Roman and Edur Velasco and published by Fernwood in 2013, examines the clash between what the authors term the “corporate offensive” and the movements of resistance on a continental level. The conflict of these forces can be seen through the prism of free trade agreements (CUFTA, NAFTA), the restrictions on social spending resulting in severe cuts to needed social services and the continuing attacks on public sector unions in all three countries (Canada, Mexico and the United States). It is through such trade agreements, cuts and attacks that business elites have sought to lock in their domestic neoliberal reforms and thereby secure and expand “safe” private investment areas and continentally integrated markets.

This ongoing transformation of all three countries of North America, the authors say, “has created an arena of struggle which can only be understood from a perspective that combines a broad class-struggle approach with a pan-continental approach.” It is further maintained that the two sets of binational working-class relationships provide the basis for the development of workers’ resistance – indeed, a labour insurgency.

The authors admit that such potential faces numerous obstacles not the least of which are to be found within those organizations that are viewed as being central to social change, namely the trade union movement. Labour organizations, the authors maintain, are not currently capable of mounting an effective worker resistance and will therefore have to be “transformed into more democratic, participatory and politically independent organizations” for this potential to be realized.

The Big Business Offensive

Part 1 of this insightful text focuses on “The Big Business Offensive” with separate chapters on Canada, Mexico and the United States. Considerable analysis and detail on the role of business elites and their institutions, the role of political elites, the importance of free trade agreements, is provided. The authors expose the oft held belief that NAFTA was imposed by the American Empire on Canada and Mexico. On the contrary the authors find, the latter two countries promoted the idea of a North-American free trade agreement (NAFTA) as a secure and comprehensive entrance into the American market. In effect, the Canadian and then Mexican business elites applied to gain entrance and expand their markets. Finally, the role of labour and its various structures plus the adequacy and inadequacy of its responses to such offensives is deciphered.

Contexts are viewed important, particularly the post-war boom versus the recovery and competition from a resurgent Europe and Japan. The impact of restrictive anti-labour legislation, such as the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 and the Landrum-Griffin Act of 1959, is analyzed. The various institutions, legislation and actors were unique to Canada compared to the United States, but the most striking differences lie in Mexico with its long history of a one-party politics, labour upsurges and state-guided capitalism.

Two Binationalisms

Part II is entitled “The Two Binationalisms” and concerns immigration and the history of transnational labour markets and labour movements. The authors discuss the difficulties facing Mexican migrants and how neoliberal globalization largely results in poor peasants and workers exchanging one kind of poverty and hardship for another either through internal relocation to the maquila zone or in cross-border immigration. In large part, Mexican immigrants have served as a reserve army of labour for the U.S. economy and entrance of Mexican workers into higher paid jobs and into American unions was very limited. Consequently, over the last few years there have been a number of Latino immigrant demonstrations demanding full citizenship, green cards and democratic rights. This discussion is highly informative, though further exploration of the uneven levels of integration into the American work force and society at large is to be welcomed.

In the case of Canada and the United States, wherein most people spoke the same language, with the notable exception of French speaking Quebec, there is a long history of movements in both directions across the border and of workers being members of the same unions, known as “international” unions. Yet the misguided implication of the text is that such unions represent the growing integration of the two working classes whereas the reality is that national unions represent more and more Canadian workers. Furthermore, it is highly questionable that such largely top-down business unions bargaining on a work-site by work-site basis, represent integration in the first place. I remain unconvinced that such “international unions” represent either continental integration or international solidarity. If working classes can’t build solidarity domestically, they won’t be successful internationally. Nonetheless, the migrations between the two countries contrast dramatically with that between Mexico and the United States.

Workers and Unions

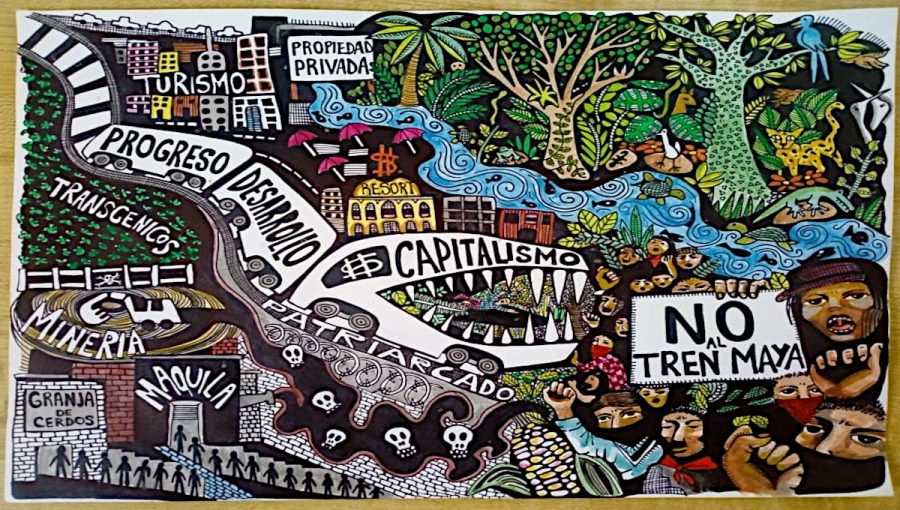

Part III discusses “Workers and Unions” focusing on responses to North American integration from below. Roman and Velasco argue that an effective fightback against the “continental capitalist offensive” necessitates a working-class response that goes beyond the local, regional and national levels. “The fightback has also to be continental.” Further, that the current culture of competition between workers for jobs must be replaced with a culture of solidarity. Here there is an interesting discussion of the limits of unions as presently constituted. The authors point out that while business fought for its own class-wide demands, unions have engaged in fragmented union-by-union, if not workplace-by-workplace, defensive battles. Given such, no class-wide viable and attractive alternative vision to business has been presented.

“The conundrum is that capitalists have developed “continental production chains and overlapping labour markets” while workers and their unions are segmented both organizationally and politically.”

The challenge of engaging members with different occupations, income levels, specific needs, racial and gender distinctions on the one hand versus fighting for the general interests of workers as a whole on the other, is raised by the authors. This is an important discussion that will undoubtedly necessitate ongoing elaboration and result in structural and ideological changes if unions are to engage in the kinds of resistance contemplated. In short, the conundrum is that capitalists have developed “continental production chains and overlapping labour markets” while workers and their unions are segmented both organizationally and politically. Competitive national strategies and fragmented union responses have proved increasingly ineffective.

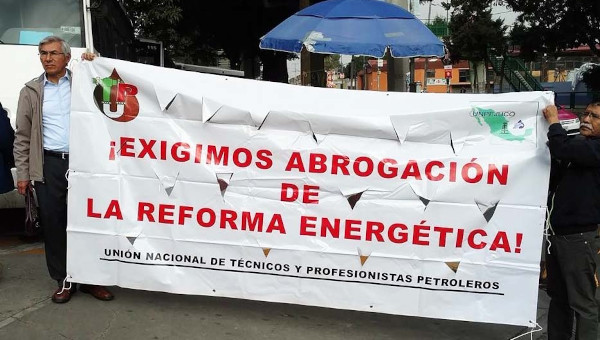

There is more, much more, in this valuable text. This review can only introduce the reader to a thought provoking and politically significant narrative. Yet I would be remiss if I didn’t end with a final word on Mexico. Roman and Velasco argue that Mexico is the “weak link” in terms of stability in North America. There is considerable material in the book on the political history of Mexico, its revolutionary heritage, its political development and evolution. Of particular importance is the growth and combative development of the Mexican working-class. Due to repression, poverty, brutal drug wars, increasing militarization, corruption and more, the regime commands only tenuous legitimacy. The authors hold that NAFTA has brought together a volatile “third world” country with two relatively stable capitalist democracies and that Mexico could well provide the spark for North American social transformation. Yet, although this is possible, in my view its likelihood is questionable at least in the short term, given the episodic and locational nature of labour upsurges, the political, regional, ethnic divisions, the violence and corruption in the Mexican trade union movement. On Mexico in particular, but also throughout the text, there is a tendency to exaggerate the size and nature of the contemporary class struggle. In my view, at this point in time, resistance is at a low point in all three countries, rather than a high point.

My reservations aside, the analysis presented by the authors and the conclusions they come to are fundamentally sound. The call for going beyond basic cooperation between unions to a profound transformation of unions into organizations fighting for the needs and aspirations of working people in all three countries is powerful and exciting. This very readable text may well prove crucial for those wanting to move beyond a national framework and encompass one that is continental and global. •

This article first published by Global Labour Journal.

Continental Crucible by Richard Roman and Edur Velasco Arregui is published by Fernwood (2013). See the book launch in Toronto, LeftStreamed No. 171.