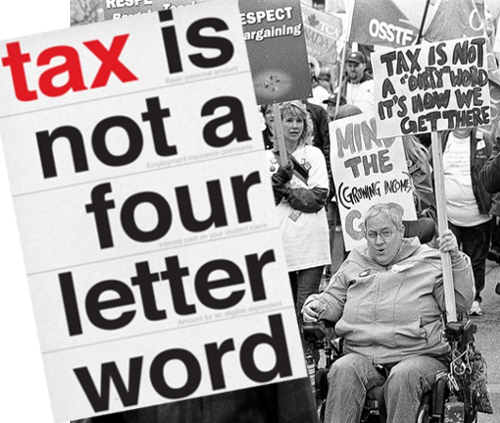

Public transit remains a crucial policy issue for the province of Ontario, but it is not clear that citizens will get good solutions any time soon. Investment in public transit is expensive, often requires raising taxes and can get bogged down in the nitty-gritty politics of neighbourhood planning, not to mention partisan competition.

In 2007, the government of Ontario tried to turn over province-wide planning for public transit to an arms-length agency, Metrolinx, in part to take the politics out of the issue. Its plan, The Big Move, is the result of years of study, planning and consultation. But its fate is questionable.

Because the Progressive Conservatives have effectively boycotted the political negotiations that characterize minority parliaments, the Ontario NDP and Liberals are currently driving policy and politics in Ontario.

Sadly, the negotiations between these two parties appear to have signed the death warrant for the desperately-needed investment strategy in public transit that Metrolinx has developed. If the Big Move didn’t die this week, it is on life support. And if it goes, so does Hamilton’s B-Line Light Rail Transit (LRT) plan.

Revenue Tools Rejected

In a March 10 interview with Hamilton Spectator columnist Andrew Dreschel, Ontario NDP leader Andrea Horwath left the impression that she favoured increasing corporate taxes to pay for increased investment in public transit in Ontario, particularly for the Big Move. But by March 12, Dreschel published a correction to his column, noting that the party currently does not support raising corporate tax rates, but rather just favours closing some corporate tax loopholes.

On March 13, the Globe and Mail reported that Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne had rejected the proposal to increase the HST or the gas tax to invest in transit.

| Table 1: Status of Proposed Metrolinx Revenue Tools | ||

|---|---|---|

| Proposal | Cost | Status |

| 1% increase in the HST | $1.5 billion | Initially rejected by Horwath, rejected by Wynne on March 13 |

| Regional gas tax | $330 million | Initially rejected by Horwath, rejected by Wynne on March 13 |

| Development Charges Amendments | $100 million | On the table |

| Parking Space Levy | $350 million | On the table |

These two developments mean that the Big Move – and Hamilton’s LRT – are nearly dead in the near term. The second wave of transit projects in the Metrolinx development strategy is ambitious and had a cost associated with it of roughly $2-billion per year. The proposed list of tools to pay for this is in table 1. The current political status of each is also listed. $2-billion is needed to fund the projects and more than $1.5-billion of that is now gone.

NDP Revenue Plan

The NDP’s constant alternative has been that the ‘average’ family should not have to pay for transit, but that ‘corporations’ should. What most people – including Andrew Dreschel – hear when Horwath says this is that the corporate tax rate would go up. However, what they are now saying they mean by this is that the NDP does not plan to actually raise corporate taxes. Instead, it plans to not implement some planned exemptions to the HST starting in 2015 and ending in 2018. You can read their plan “Back To Business At Queen’s Park.”

This all goes back to the implementation of the Harmonized Sales Tax (HST) in 2009. The whole point of that proposal was to make the tax system more efficient, so the tax was not to be levied on business inputs. However, certain controversial expenses (e.g. entertainment and meals) were exempted from this. These exemptions start to expire in 2015 and fully expire in 2018. So when the Ontario NDP says that it wants to raise corporate taxes, what it really says is that it plans to close loopholes that do not currently exist.

The party calculates that this could raise (sorry, prevent the loss of!) $1.3-billion annually by 2018. That’s 2018, not 2015. In addition to this, the party expects to reap an extra $300-million attributable to increased compliance because they’re going to get tough on corporations and from a few other measures.

If we’re generous to the NDP, we can count that $1.6-billion as revenue.

| Table 2: Hypothetical NDP Mix of Revenues | |

|---|---|

| Proposal | Cost |

| Preventing lost revenue | $1.6-billion |

| Parking Space Levy | $330-million |

| Development Charges | $100-million |

| Total | $2.03-billion |

Let’s further assume that Horwath can find it in herself to support the two remaining revenue tools from Metrolinx’ revenue tools (development charges and the parking space levy) and add those to the mix. That means, we’re looking at something like this (Table 2) for fiscal year 2018.

So, in this generous scenario, Horwath can still claim that she can cover the cost of the Big Move without the other investment tools.

Except for two big problems.

Two Big Problems

First, this only starts in 2018, not in 2015. Second, this only works if one assumes that every single cent of this already generous vision of increased revenues from businesses goes straight to transit. Not a cent of this can go to address poverty, address waiting lists in hospitals, address the fact that Ontario has the lowest rate of per-student funding for post-secondary education in Canada or address the fact that we still do not have a public and accessible child care system in this province.

This is not plausible. Those are important priorities and the interest groups that represent them are at Queen’s Park right now trying to make the case for their priorities.

At this point, one way of resurrecting the Big Move would be if Wynne were to propose increasing the corporate tax rate in the negotiations to the budget. Maybe in such a scenario, Horwath might step down from her Rob Ford-like aversion to tax increases to cover some of the revenue. Time will tell.

What is certain, however, is the following:

There is a pressing public policy problem facing the citizens of Ontario. The provincial government wisely attempted to depoliticize the issue by handing over proposals to a technocratic and non-partisan body.

Rather than supporting that public intervention in the service of something we might call the public interest and concentrating on fighting an election on, say, the fact that the provincial government has mismanaged the electricity file in a horrible way, the NDP has re-politicized the issue and, quite possibly, doomed it in the process.

NDP War on Taxes and Public Services

When I joined the NDP in Alberta in 1993, the party had just been eliminated from the Alberta legislature and reduced to nine seats in the Federal House of Commons. I probably joined partly out of a deep personal tendency to support the underdog, but I also joined the party because it didn’t seem right to me that the public sector was being framed as the source of all the problems in our society.

It seemed to me to be important to defend the idea that public solutions to problems are often more efficient than strictly private solutions. The Ontario NDP has nothing to do with that.

I still identify as a New Democrat. Somewhere, I’m pretty sure you can find an Ontario party membership card. But I’m sitting this one out. Andrea Horwath can wage war on taxes and public services without my money, my time or my vote and I strongly urge other Ontario New Democrats to do the same. •

This article first appeared on Raise The Hammer.org website.