The Factions in COSATU, Economic Fear-Mongering and

the State We’re In

It is reported that Lenin once observed that there are decades when nothing happens and then there are weeks when decades happen. British Labour Party Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, was to similarly explore the vicissitudes of political time when he remarked that: “A week is a long time in politics.” August is a strange month in South Africa. We can either see it as the worst of a long winter or as the beginning of spring.

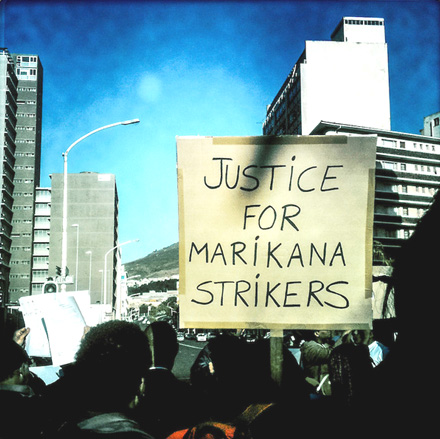

It’s too early to say whether the week beginning the 12 August 2013 was such a week as might have been thought of by either the revolutionary Lenin or the reformist Wilson. Yet three events in that week suggest that there were indeed such momentous shifts taking place. These events are the COSATU NEC’s decision to suspend its General Secretary, Zwelinzima Vavi, the convening of a memorial for the murdered workers of Marikana one year after that massacre, and (very much less dramatically) the meeting of the BRICS Business Council.

It’s too early to say whether the week beginning the 12 August 2013 was such a week as might have been thought of by either the revolutionary Lenin or the reformist Wilson. Yet three events in that week suggest that there were indeed such momentous shifts taking place. These events are the COSATU NEC’s decision to suspend its General Secretary, Zwelinzima Vavi, the convening of a memorial for the murdered workers of Marikana one year after that massacre, and (very much less dramatically) the meeting of the BRICS Business Council.

The Agenda of the BRICS Countries

Let’s start with the meeting of the BRICS Business Council – an event chaired by Patrice Motsepe and in many ways bit of a damp squib, at which Trade Minister, Rob Davies, saluted the fall in the South African currency, the rand, as good for South Africa. Remember that Brazil, Russia, India and China (BRIC), who got together in 2009, were joined by South Africa in 2010 to create the BRICS as an alliance of countries – important regional imperialist powers – who share the desire to have an alternate currency to the dollar as the world’s trading currency and reserve currency. In February this year South Africa hosted the BRICS meeting in Durban. This group of countries – dubbed “emerging economies” by the business media – had shown growth over the 2008 to 2012 period way beyond what was occurring in the crisis-ridden centres of capitalism in the U.S., Europe and Japan. Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa had done very well in the midst of the biggest global crisis of capitalism in the last 80 years largely because investors had borrowed money in the nerve centres of capitalism – where money had become incredibly cheap – and invested these in countries with large mineral resources and high real interest rates. As a result these countries were the beneficiaries of the so-called “carry trade” and their stock exchanges boomed with bond markets showing a huge demand from foreign investors. They came to be seen as centres of excellence in an otherwise capitalist world of investment mediocrity.

Buoyed by their status the other BRICS countries pitched their tents next to China in its currency wars with the USA and declared that they would trade in intra-BRICS currencies (instead of the dollar) and set up their own BRICS bank (in the turf now dominated by the IMF and the World Bank). The BRICS agenda reflected both the ambitions as well as the weaknesses of South African capital.

South Africa’s interest in the currency question has been prompted by the fact that its principal monopolies – Anglo-American, De Beers, Liberty, and Old Mutual etc., relocated their principal listings to London but have their sources of profits in South Africa in the form of a rand-denominated assets. As such their earnings in the form of profits and dividends are directly dependent on having a high rand exchange rate in comparison with the dollar, the euro and the pound. In the midst of the global crisis since 2008 the rand benefited from the carry trade as investment in bonds and stocks in South Africa flooded in and the rand’s exchange value rose up. In 2011 and 2012 the rand was the strongest currency in global markets.

This was the source of what Alan Greenspan famously called the “irrational exuberance” of South African markets. However this was always going to be a fragile benefit because the hot money went into bonds, real estate and consumption rather than long-term fixed investment and because it was entirely reliant on the U.S. Federal Reserve continuing to print money in the form of quantitative easing. This has been the stock in trade of British and U.S. central bank policies in the last few years. But as soon as the Fed began to suggest that it may well rein in the quantitative easing and stop printing such easy money investors immediately began to shift the hot money out of South Africa, Brazil, Russia, Turkey and so on. India is now sinking into a quagmire of bankruptcy on its balance of payments as the hot money flows out. The Indian Rupee dropped to its lowest level in 18 years while the Brazilian Real collapsed hardly less dramatically in 2013 (causing higher World Cup costs and adding to the toxic cocktail that sparked the mass protests in Brazil).

Since mid-2012 the rand, similarly, has been spiralling downwards from its highs of the 2009 to 2011 period. This drop in the rand has got nothing to do with the strikes in the mining sector or the so-called “policy uncertainty” on the part of South African government or any other targets which the business media likes to aim at. Rather this collapse has got everything to do with the South Africa’s insertion in global markets and the changing response of speculators to the quantitative easing rounds in the USA. Now there is a run on the rand and the rand is at a 4 month low against the dollar. This is a serious problem for South African capital

Conceived of in the rosy flush of 2009 and aiming to scale the heights of a BRICS Bank and a new global trading currency, the BRICS met in Durban at a time when the rosy flush was beginning to pale. In the week of the 12 August 2013 India’s accounts revealed deficits on both its current and capital accounts as the hot money dramatically moved out. The BRICS Business Council continued its scheduled meeting, chaired by BEE beneficiary, Patrice Motsepe, rather than any of SA’s real heavyweights. All the talk of a BRICS Bank and a new currency is now placed on a back-burner. Suddenly in mid-August Rob Davies seeks solace in the falling rand. How the mighty have fallen…

COSATU Politics

The week of the 12 August was also marked by the Central Executive Committee (CEC) of COSATU deciding to suspend Zwelinzima Vavi on charges of sexual impropriety, amidst open contestation between NUMSA on the side of Vavi, and NUM, SADTU and NEHAWU aligned with SACP Central Committee members, President S’dumo Dlamini, and NUM’s Frans Baleni.

Since Jacob Zuma‘s ascendancy into power at Polokwane and the subsequent 2009 elections which made him President of the country, we have witnessed increasing tension within affiliates of COSATU and between some leaders and the SACP (South African Communist Party). The immediate causes for COSATU’s infighting lie in the break-up of the COSATU–SACP–ANCYL axis which drove Thabo Mbeki out and Zuma into power. That agenda had little to do, as we now know, with some kind of Left-Right programmatic tension within the ANC, or that Zuma, as against Mbeki, was a more “pro-poor candidate,” but was about a series of manoeuvres to get into influential positions in the state machinery.

Both the SACP and COSATU got appropriately rewarded with cabinet ministers. Julius Malema’s Youth League got its own rewards in the form of both cabinet ministers and lucrative business tenders from national and provincial governments. But whereas Malema’s sin was ingratitude and over-ambitiousness, Vavi’s was to renege of an assurance to move on from COSATU general secretary in 2010 and not covet Nzimande’s leadership position in the SACP. So the SACP’s grubby Stalinist hands have been itching to get at Vavi since then. Vavi’s abuse of power and sexual indiscretions have provided the SACP with the necessary ammunition. And so the spectre of the implosion of COSATU, once the finest expression of democratic mass resistance against apartheid, now looms – sadly, as T. S. Eliot once warned, “Not with a bang but a whimper.”

But the real sources of COSATU’s problems lie much deeper than this leadership spat. At a time when Marikana unleashed a wave of strikes (which COSATU ignored) – in sectors such as mining and farming (not known for many years for such militancy) – and with almost 10 years of unabating community revolts, these should have been circumstances in which a militant COSATU would have thrived, grown and provided leadership. Yet its demise is immanent precisely at this time and it all comes to a head in mid August, the week of the anniversary of Marikana.

It has been notable that despite media hysteria about the “strike season” how much COSATU unions are desperately trying not to strike. NUM declares a dispute with the Chamber of Mines and then calls for a “cooling down period,” ostensibly to give the Chamber a chance to make a more “serious offer.” SACTWU ballots its members for strike in the clothing sector, gets a 70 per cent approval to strike from its members, and then decides not to. Only at NUMSA – the union adopting the most militant position in the COSATU leadership spat – does a strike actually proceed in the auto sector.

The underlying causes for the problems within COSATU lie in the major structural changes that have happened to the working-class over the last 20 years of neoliberal capitalism and the re-alignment of COSATU’s membership. In that period the neoliberal attacks on the working-class have seen a shift away from full employment and fixed employment toward casualization, informalization and unemployment in the case of the world of work, and the abandonment by the state of the sphere of reproduction of the working-class – from apartheid brick houses in townships to shacks in informal settlements; from Bantu education to no education or privatized education; from discriminatory services to no services or commodified services – beyond the reach of the poor. As a result the working-class in South Africa is now largely an unemployed, casualized, semi-homeless mass.

“COSATU is no longer a representative force of the majority of the working-class. This has become a feature of the class and labour landscape over the last 10 to 15 years.”

By way of contrast COSATU increasingly became a federation of unions drawing from white collar workers, permanent workers and skilled workers. COSATU shop stewards and worker leaders are now full-time shop stewards living in the world of negotiations, subsidized cars and houses, daily rubbing shoulders with the HR departments of their bosses and moving through the many committees and task teams associated with national negotiating fora. As such COSATU is no longer a representative force of the majority of the working-class. This has become a feature of the class and labour landscape over the last 10 to 15 years and has even been noted by COSATU’s own research arm, NALEDI.

With union membership and leadership distant from the critical issues facing the working-class COSATU has become a home for careerism and a pathway for senior leaders to move into government and into the Cabinet. The case of NUM, which was so graphically revealed after Marikana in the way the general secretary was earning R300,000 per month and where the worker leaders were full-time shop stewards on the payroll of the companies and enjoying perks and the union even owning shares in the bank that loaned money to workers, is not a an exception but is replicated in other unions in the way all have investment companies and are schooled on the circuits of negotiating fora, Alliance meetings etc.

A decisive ingredient in these developments has been the South African Communist Party. The SACP and its National Democratic Revolution – in which the “first stage” would be a capitalist democracy presided over by the ANC – has long abandoned any notions of socialism, beyond the occasional rhetorical flourishes, and has become completely integrated into an avowedly capitalist state. Both its general secretaries are Cabinet ministers under Zuma. And even under Mbeki and Mandela the secret in ANC circles was always to appoint SACP heavyweights into senior Cabinet ministers which had unpopular tasks to carry out – privatization, e-tolling etc. The Communist Party has comfortably combined the rhetoric of socialism at May Day rallies with implementing neoliberal policies in government.

It has always been the SACP which has been the glue which held the Tripartite Alliance together. But as the ANC has shifted so has the SACP. In the recent past the SACP played the role of a “loyal opposition” – criticising government policies such as GEAR (Growth, Employment and Redistribution) while remaining loyal to the ANC and its leadership of what they called the National Democratic Revolution. Not only did the SACP remain loyal it gave a left ideological spin to ANC’s embrace of neoliberaism famously accepting the privatization programme announced by then deputy president Mbeki in 1995 as long as privatization was done on a “case by case basis” and not on “ideological grounds.” How did they resolve this tension? In the first phase of the Mandela administration the SACP blamed apartheid bureaucrats and World Bank consultants – advising departmental managers in the state – for misleading the ANC in government and allowing the neoliberal agenda to creep in. And so the goal of the SACP – and it dragged COSATU along with this given its ideological hegemony within COSATU – was to ensure “transformation within the state” and thus dedicate its cadre to hold to this line. Despite the avowedly neoliberal GEAR being crafted under the Mandela presidency as a home-grown structural adjustment programme the SACP stuck to this loyal, but critical, arrangement. Key SACP Central Committee members served in the cabinet.

But increasingly the Mbeki presidency was marked by greater centralization of power not only within government but within the ANC itself, and the two became indistinguishable. And so the space for SACP luminaries to staff key government policy portfolios became limited and Mbeki used to delight in showing his ability to use the SACP’s own “Marxist-sounding” language against them, to slap them down. So under the Mbeki regime the SACP coined the term the “Class of 96” – unnamed ANC and business interests who were to blame for GEAR and its programme. But that “Class of 96,” according to the SACP, would have its way if the SACP and COSATU did not continue to support an ANC government.

Underlying this loyalty was an increasing integration of the SACP into state structures – like Parliament, the cabinet, the provincial and local government structures, the Development Agencies etc.

And then since 2007 the SACP-COSATU-ANCYL coalition rallied to install Jacob Zuma using his travails under Mbeki to get undertakings to being placed at the centre of power in the new administration. Now, being at the centre of Zuma’s administration, the SACP has seized any pretence of being any kind of opposition at all. Instead it has positioned itself as the Rottweiler of the ANC government – the first to attack Julius Malema (not when he was the favoured son at the head of the Youth League and an ally within the Zuma coalition but when he began to call for nationalization of the mines and accused Zuma of selling out to white capital). Similarly it has been the SACP that has been the most vociferous in its attacks of COSATU and Vavi’s public criticisms of the ANC government.

The current spats within COSATU are driven by the SACP and its aligned union leaders. The process of integration of the SACP into the state is now complete. Blade Nzimande the cabinet minister and Blade Nzimande the SACP general secretary are now one. And Nzimande’s threats in mid August that: “Anyone contemplating leaving COSATU [as NUMSA has warned] will first have to deal with the SACP and its red door” represent the worst of a new disease in our body politic: the mixture of Stalinism with neoliberalism. All this came to a head in the week of 12 August.

Anniversary of the Marikana Massacre

And then that fateful week in August had a third and most important significance – it was the week of the anniversary of the Marikana massacre. And while workers commemorated that day, 16th of August, the ANC, in and out of government, the SACP, COSATU and NUM all boycotted. Vavi held his press conference on 16 August choosing to rail against government conspiracies but finding no time to make common cause with the workers of Marikana. A range of churches and parties came to pay their respects, thereby at least acknowledging that something important needed to be acknowledged.

In the meantime the media, the parties such as the Democratic Alliance (DA), Agang, etc., hardly found time to doff their caps at the Marikana workers on 16 August before unleashing a tidal wave of criticism against the “unrealistic” wage demands of mine workers – the very demands that made the police shoot them. Rarely can hypocrisy be so bald-faced.

In the meantime the media, the parties such as the Democratic Alliance (DA), Agang, etc., hardly found time to doff their caps at the Marikana workers on 16 August before unleashing a tidal wave of criticism against the “unrealistic” wage demands of mine workers – the very demands that made the police shoot them. Rarely can hypocrisy be so bald-faced.

The problem facing the South African elite is a problem in politics rather than pure economics. The configuration which made possible the legitimacy of the neoliberal project in South Africa is now under threat. We should recall that although South Africa now is the most unequal country in the world and although the poor in South Africa have known nothing else other than joblessness, cuts in public spending, lack of housing etc., since 1994 this was offset by the joy of having the liberation movement in power as the governing party. The ANC and its legitimacy as the party of liberation was key to the project of shifting South Africa toward the kind of neoliberal nirvana that Thatcher and her acolytes could only dream of. South African companies became some of the most important in the world and the country became a haven for investment precisely because the ANC could preside over an electorate that elected it over and over again despite its non-delivery of any of its electoral promises. And alongside the ANC stood its alliance partners – the South African Communist Party and COSATU. The former serving as the glue that holds the Alliance together, while COSATU served to mediate conflict by acting as both a register of conflicts in workplaces but, at the same time, delivering votes to the ANC in elections.

This symbiotic relationship between COSATU, the Communist Party and the ruling party has delivered since the 1994 dawn of democracy. Now that COSATU’s legitimacy is in question, its erstwhile largest affiliate, NUM, is disgraced, alongside the SACP. And with this goes the legitimacy of the ANC itself.

Some more prescient commentators – notably Carol Paton of the Business Day – have identified the fact that the DA’s dream of a new alignment of SA politics emerging out of the disintegration of the Tripartite Alliance would see the ANC’s “liberal constitutionalists” make common cause with the DA and forge a liberal consensus to the right of the ANC, may well prove to be wrong. Instead the threat of a Vavi-inspired break from the Alliance and the proliferation of left groups within the Marikana aftermath speaks to a very different alignment – challenges coming from contestations to the Left of the ANC.

Alistair Sparks attempts to analyse this same possibility of a new alignment in politics by fingering Jacob Zuma for the intrigues against Vavi amongst COSATU’s affiliates. Both though, however, tend to view developments with lenses largely focussed on the 2014 elections and both too readily seek out easy suspects to place at the centre – from Vavi to the noises coming out of Julius Malema’s Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF).

But what is the make-up of these re-alignments? The favourite line of the media is that the ANC is anti-business and that “policy uncertainty” bedevils investment. Yet the ANC government has overseen the emergence of South Africa’s global monopolies, the free movement of capital in and out of the country and the greatest shift in wealth from the poor to the rich in 40 years. So much of this is about a form of advocacy – lobbying government via the media to be even more investor-friendly, was the case of the space given to the tearful Anglo CEO Mark Cutifani to bemoan the fact that none of the recommendations added by Big Mining to the revised Mining Bill have so far been taken on board.

The ANC

In the meantime the latest summit of the Tripartite Alliance meets and while some sections of the media contemplated some kind of dispute within the ranks and that the NDP might be the basis of such a dispute, and that the absent Zwelinzima Vavi might be ‘the elephant in the room’ the outcome was, entirely predictable, a unified face. We have now been treated to nearly 20 years of such speculation of tensions and possible splits within the Tripartite Alliance only to have such speculations proven wrong. The truth is that all the individuals who meet at these summits are loyal ANC members and all the senior COSATU leaders are SACP members who do not need summits to meet and exchange views. The SACP, in turn, is led by two cabinet ministers who presumably have endorsed government policies wearing their day-job hats. The only surprise associated with the latest Tripartite Alliance Summit was the idea that anyone still had the naivete to expect surprises.

But if we look deeper and beyond the ANC, SACP and COSATU and if we grant the post Marikana striking workers and their self-organized committees the agency and integrity that centres them in our analysis – together with the ongoing community “service delivery revolts” then we have a very different picture of dramatic changes of August.

What we then see is the entry into the political drama of forces who have in the recent past been condemned to be off-stage while the ‘serious’ formations of civil society – parliament, big business, the well-known political parties – ply their craft and keep us enthralled. One year on from the massacre at Marikana and tectonic plates are shifting in South Africa – shifts that Marikana exposed and that its aftermath continues. These changes are about deeper structural and conjunctural dynamics that have impacted on all the political forces in SA.

We can view all of these developments paralyzed by the fear-mongering of the business media fanning the flames of immanent economic collapse caused by “unreasonable demands” by militant workers in the mining sector, or “ill-disciplined” community activists offending us with their poo-protests. We can delegitimize these struggles by association with Julius Malema’s EFF. And then we may as well join all of those who boycotted the Marikana memorial.

But if we view these developments through the spectacles of the possibility of a new movement untainted by the machinations and the compromises made since 1990, then the emerging strike committees, the militancy displayed by workers on the mines and on the farms and the ongoing protests at community level are signs of a new movement for social justice is emerging. Then these are instances for celebration rather than fear. And in that sense August is the end of winter and heralds a new spring.

Much of the confusion is generated by the rhetorical flourishes which emanate from the various formations. The ANC was until recently the liberation movement, its leaders call one another “comrade” and they swear commitment to the National Democratic Revolution. Except that after nearly 20 years of being the ruling party no one still questions the credentials of the ANC as the party that delivers for BIG Business. In fact everyone understands that the ANC has to marry the traditions of its past as a liberation movement with its role as the ruling party of neoliberalism in order to make South Africa precisely the capitalist success story that it is.

So the SACP must be a force on the Left because it is, after all, a “communist party,” and its leaders sometimes don red caps and make radical speeches. Julius Malema’s EFF must be Left wing because it wants nationalization of the mines and its leaders favour red for their headgear. COSATU too, it is presumed, is an organization of the working-class and has history of strikes and militant campaigns – including publicly trying to stop labour broker and the Youth Wage Subsidy. But if we look beyond the rhetoric and focus on what these formations actually consist of then we have a very different picture – one which explains much better the nature of political alignments we are likely to see in the next period and which will shape the choices we really face.

Malema’s EFF consists of a layer of disgruntled tenderpreneurs and small and not-so-small businesspeople, who have not scaled the heights of the favoured BEE heavyweights, like Cyril Ramophose, Patrice Motsepe, Tokyo Sexwale and the like. Whereas these owe their existence to being first in the queue in the Mandel-Mbeki eras the EFF late-arrivals are those for whom the opportunities have become more limited. Nationalization is not a left wing programme of social transformation but a campaign to elevate their economic aspirations. Appealing to disgruntled youth is the contemporary equivalent of Hitler’s appeals to German nationalism. This is not the stuff of a Left alignment. •

An earlier version of this article was published on the South African Civil Society Information Service website.