Could Election Reform Make a Difference?

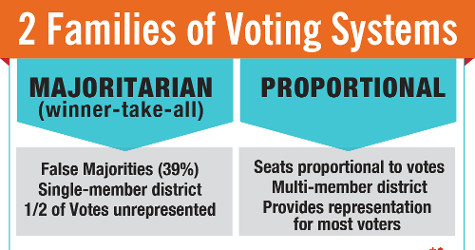

In the May Federal election, Stephen Harper won a majority government without winning a majority of the vote. Only 39.6 per cent of the population voted Conservative while 60 per cent voted against. Much discussion has focused on the election results and what to do about the Harper majority. But relatively little of this has focused on the electoral system.

The current first-past-the-post electoral system rewards the winning candidate in each riding, while votes cast for losing candidates are not taken into account. When the parliamentary results are added up, the winning party is often rewarded with a disproportionately high number of total seats. Losing parties, especially third and smaller parties without a strong geographic centred constituency, are generally highly underrepresented in relation to their overall share of the vote.

In random and often highly unpredictable ways (depending on vote splits), this system often quite inaccurately reflects the popular vote. A far more accurate proportional system would have turned the Harper majority into a weak and tenuous minority government, or opened the door to other government possibilities.

| Number of Seats Won | ||

|---|---|---|

| Party | First-Past-The-Post | Proportional |

| Conservative | 166 | 123 |

| NDP | 103 | 95 |

| Liberal | 34 | 59 |

| Bloc Quebecois | 4 | 19 |

| Green | 1 | 12 |

The federal NDP as a third party has consistently been underrepresented in parliament. In the recent election this continued to be the case in some provinces but not overall. The NDP won 0 seats in Saskatchewan with 33 per cent of the vote.

At the same time, the NDP won a highly disproportionate number of seats in Quebec, while the BQ shifted to being sharply underrepresented. Elizabeth May might have made an individual breakthrough, but small parties like the Greens remain major losers under the first-past-the-post system.

Trapped by the Rules of the Game

Some on the left tried to outsmart the existing system by advocating strategic or tactical voting for the candidate best positioned to defeat Harper. This approach failed to achieve its goals of stopping a Harper majority. The Conservatives skilfully played the game to win a majority government by both appealing to their right wing base and targeting specific ridings and groups (for example, suburbs containing large number of immigrants and other people of colour).

Sixty per cent may oppose Harper, but these voters don’t necessarily support the Liberal agenda. The Liberal vote fell sharply, including in seats they had previously held, with some shifting to the Conservatives, and more to the NDP.

Notwithstanding the NDP surge, the prospect of more Conservative majority governments means the discussion of how to avoid vote splitting will continue. But the terms of the discussion are shifting, with more chatter about either a Liberal NDP merger or a future electoral coalition. Not everyone thinks this is desirable. The search for an anybody-but-Harper alternative could drag us down into a mire of lesser evilism. However this seems unlikely to happen any time soon. The NDP will seek to consolidate its position as the alternative government in waiting, while the Liberals will seek to rebound and recapture their past status.

Notwithstanding the NDP surge, the prospect of more Conservative majority governments means the discussion of how to avoid vote splitting will continue. But the terms of the discussion are shifting, with more chatter about either a Liberal NDP merger or a future electoral coalition. Not everyone thinks this is desirable. The search for an anybody-but-Harper alternative could drag us down into a mire of lesser evilism. However this seems unlikely to happen any time soon. The NDP will seek to consolidate its position as the alternative government in waiting, while the Liberals will seek to rebound and recapture their past status.

While the ruling class may prefer a Conservative majority, the same cannot be said for those of us who will be sharply attacked and suffer the consequences of a Harper majority which is not a social majority. The most straightforward way to get rid of such artificially created majority governments would be to scrap the first-past-the-post system and replace it with a fairer system.

Not All Alternatives are Equal

One widely promoted alternative model is the mixed-member proportional system. Some members are elected in constituencies, while other seats are allocated to reflect the party’s share of the total vote. This cleanly deals with representational balance, and would tend to encourage rather than discourage the formation of new parties (providing there is low threshold of one to two per cent for parties to be represented in parliament).

However not everyone favours this model, in which non-constituency representatives would be selected from party lists. Some, including those influenced by radical democratic green or anarchist ideas, feel this gives too much power to political parties and not enough to citizens.

In British Columbia, this led to a recommendation for and vote on a variant of the single transferable vote system. This idea inspired some people but not others. Not everyone liked or supported some of the practical consequences, such as the creation of large multi-member constituencies (the city of Vancouver would have divided into two seven-member ridings). This proposal was defeated in a 2009 referendum, receiving less than 40 per cent of the vote

Many alternative voting systems focus on ranking preferences and transferring votes to second or third preferences until a majority is achieved. This has some merit. The first-past-the-post system encourages or prompt people to vote for candidates that have a legitimate shot at winning. By contrast, a transferable vote could modestly enlarge the space for smaller and newer parties.

In many ridings the NDP is the most left wing option on the ballot, given that the Green Party refuses to self-identify as a left wing party. In a limited number of ridings there may be a Communist or Marxist-Leninist candidate. However, such candidates, whatever legitimate issues they raise, tend to reap very low scores in part because of too much negative baggage, but more fundamentally because of the incentive to vote for a candidate who might win.

However the overall effect of second preference model would be to continue to disproportionately allocate seats to major or mainstream parties, and perpetuate patterns of lesser-evilism in voting.

There is no perfect system of voting that will resolve all problems. However, as long as disaffection with the existing system remains high, this will continue to be a topic of ongoing discussion.

Electoral reform will only happen if significant forces push for it, and it corresponds to a strong wave of discontent with the existing system. Neither the Conservatives nor the Liberals have an interest in changing the system.

Will the federal NDP, which has relatively consistently supported change, continue to push the issue? Who else will step forward?

At this point it seems unlikely that the issue will be put on the front burner. Possibilities of any federal referendum seem remote. In some provinces there have been votes. But the campaigns have been conducted on a single issue democratic basis and have failed to pass.

A Priority for the Left?

Is election reform a priority for today’s left?

To answer this question we need to look at both the real limits of electoral reform and what it could potentially accomplish. A more representative voting system is not a substitute for other needed democratic reforms to make the government and state institutions accountable to the people.

We need to have measures such as feasible recall provisions to control politicians and governments who lie about their agenda during campaigns, and break their promises as soon as they take office. The arbitrary powers of the Prime Minister (and his unelected advisers) need to be curbed. Compulsive government secrecy needs to be scrapped in favour of free access to information. State institutions, including intelligence agencies, the police, the military and the bureaucracy need to be brought under public control. There is no level playing field unless we limit the power of money (campaign funding, influence peddling) and the bias of the corporate media.

Democracy is about far more than voting every few years. We need to envision transferring power back to the people, democratizing many aspects of work and life, and creating forms of workers’ and community control.

Meanwhile we need to push for badly needed reforms and stop existing social programs from being slashed under the Harper austerity agenda. This requires us to organize and to engage in struggles with the aim of creating mass movements. Such struggles are our primary means of self-defense, and have sometimes derailed right wing measures. When combined with consistent efforts to challenge dominant ideas and change consciousness, they can lay the groundwork to get rid of right wing governments.

That said, right wing governments need not only to be opposed in the streets, but defeated at the polls. But the current electoral system does little to inspire or motivate people to vote.

Increasing numbers of people (non-status migrants, temporary workers, non-citizens and especially youth) who can’t, won’t or don’t vote. Some on the left have well-grounded reasons for not voting. Arguments include: the Canadian state is illegitimate; elections can’t change the world; I dislike all of the parties and candidates; or politicians of all stripes routinely break promises and/or are corrupt.

Many of these critics are actively working to change the world through a wide variety of other means. But most often not voting merely reflects a widespread mood of apolitical cynicism which extends to disengagement from any collective effort to change the world.

I am not an electoralist, but I do vote. Governments continue to have some power over our lives, and I dislike being governed by purely capitalist parties who act against my interests and beliefs. When reformist parties make and deliver upon promises that improve lives, this can encourage us to expect and demand more.

Restricted Choices

It can be argued that the increased NDP vote represents some level of class polarization and a shift to the left in popular thinking. However analysis of the NDP campaign and platform leads to other conclusions. Although the NDP advocated a few limited reforms which resonated well, it failed to challenge the fundamentals of the market driven neoliberal model.

In its origins and character, the NDP is at least partially different than the Democratic Party in the United States. This will likely remain the case barring a merger with the Liberals. However as a potential government-in-waiting, the NDP leadership and its advisers are likely to try and move the party even more to the centre. Will individual NDP caucus members submit to this pressure or try and play a more independent role?

“One way to deal with the problem is to seek to create new parties of the left which are far more oppositional to the neoliberal capitalist model, integrating feminist, anti-racist and ecological concerns.”

Those of us who disagree with the centerist trajectory of the NDP leadership and are looking for more left wing alternatives are likely to be disappointed and left out in the cold. It is discouraging and unhealthy for democracy to be subject to a system in which voices to the left of the NDP have no presence inside parliament and are largely confined to small pockets of resistance from the margins.

One way to deal with the problem is to seek to create new parties of the left which are far more oppositional to the neoliberal capitalist model, integrating feminist, anti-racist and ecological concerns. Such parties would be rooted and linked to social struggle, but would contest elections as one way to gain influence in society. This has worked to some degree in helping to create alternatives in Europe; especially in countries which don’t have a first past the post electoral system.

However, prospects for creating such alternatives are much dimmer under the first-past-the-post system. And as long as this framework remains intact, we are likely to be stuck with very limited choices at the level of electoral politics. Moreover, here in the Canadian state the times are not particularly propitious. There is not a rise in mass based struggles or mass based radicalization with roots in the working-class that can be the basis for such party-building.

Meanwhile the federal NDP, once perceived as stagnant and largely irrelevant at the federal level, has become more of a force. This may be an improvement in some respects. However, the NDP surge also carries risks. Some movements could become subordinated to the NDP agenda. And there could be pressure, especially in the labour movement, to limit or tone down efforts to mobilize against the Harper cuts in favour of a focus on electing the NDP in 2015.

Nonetheless, the radical left needs to figure out to navigate the new situation and try to place our own demands on the NDP. We should try and reach out to those who support the NDP. But ultimately we have no control over its direction. Some may attempt to change the NDP from the inside. But many others feel this is a lost cause, especially given the overall evolution of social democratic parties on an international scale.

In the absence of prospects for building an alternative new left party, many activists will focus their energy on the priorities of resisting attacks and rooting themselves in social movements and communities.

The need to build political alternatives to the left of the NDP remains. But there appears to be very little short term prospect of accomplishing this (especially at the level of parties contesting elections). There are embryonic attempts at new models of organization such as the Greater Toronto Workers’ Assembly. However in most places, including Vancouver, such models don’t exist and alternative forms remain to be built down the road. In the interim, many activists will focus their priorities on resisting attacks and rooting themselves in communities and social movements. •

This article first appeared on the New Socialist webzine.