Portugal: Left Bloc Fires up to Fight Austerity

When the 548 delegates to the seventh national convention of Portugal’s Left Bloc came together in a vast sports hall in Lisbon over May 7-8, they had two big questions to answer. The first was what alternative should they propose at the June 5, 2011, Portuguese elections to the €78-billion (about $108-billion CAD) “rescue package” negotiated between the European Union, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund (the “troika”) and the Socialist Party

(PS) government of Prime Minister Jose Socrates?

The second was how to build greater unity among all those forces opposed to austerity – representing millions of Portuguese – so that a government of the left becomes thinkable in a country used to a back-and-forth shuffle of PS and Social Democratic Party (PDS) administrations?

As its convention met, the polls showed the Left Bloc at 7% – behind the Democratic Unity Coalition (CDU), which involves the Portuguese Communist Party (PCP) plus Greens at 7.4%. The conservative Democratic and Social Centre-People’s Party (CDS-PP) was at 10.5%, the PS at 34.8% and the PDS at 37%. But a huge 45.3% of those polled refused to say how they would vote, or were yet to make up their minds.

With the combined Left Bloc and PCP vote at more than 20% in recent years and PS supporters never so disillusioned, a left government of some kind, while still unlikely, was at least thinkable.

Resistance and Resignation

Portugal is torn between resistance and resignation. The resistance has come in the form of a general strike in November and a 300,000-strong Lisbon protest of young people – the self-styled “generation on the scrapheap” – on March 12. The resignation shows in a 40% abstention rate in elections and sizeable support for the troika’s package, seen by many as taking the country out of the hands of corrupt and incompetent politicians.

The immediate trigger of the June 5 election and the troika package was the March 23 resignation of the PS minority government. This came after the PDS and CDS-PP finally joined with the Left Bloc and CDU to reject Socrates’ fourth emergency budget in a year. The right-wing parties had backed the three previous budgets and also abstained on a Left Bloc no-confidence motion in Socrates on March 10.

The budget had aimed to reassure financial markets that Portugal, like neighbouring Spain, could get its public sector debt under control through welfare cuts, privatization and public sector cutbacks. But, unlike the Spanish government, Socrates found no allies for his brutal plan.

But the interest rate on Portuguese public debt soon surged toward 10%. The caretaker PM, who had earlier said 10 million Portuguese stand between “us and the IMF” and had allegedly tried to induce Brazil and Venezuela to buy Portuguese government bonds, finally went cap in hand to Brussels.

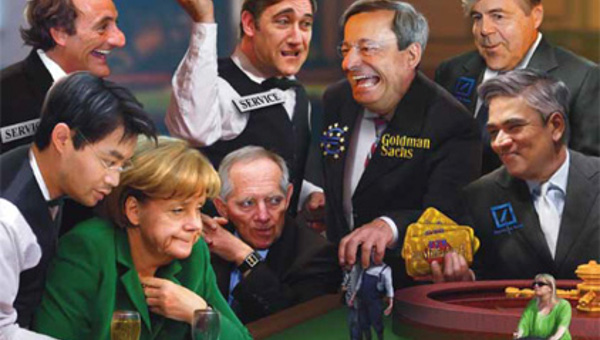

The election is a referendum on the troika’s package, which will deepen recession, unemployment and social misery in Western Europe’s poorest country. Despite being a rework of Socrates’ rejected budget, the package is supported by the PSD and CDU: their election fight with the PS will be over how the pain of the package is to be spread. At the Left Bloc convention, debate centred on how to approach the public debt, a growing part of which is due to bailing out the private banks.

Left Bloc leader Francisco Louca‘s opening address was targeted at concerned SP voters, explaining the pain that “the biggest shift to the right in PS history” would bring, and accusing Socrates of irresponsibility. Louca said:

“He didn’t explain where €1.4-billion for the health budget will be found; how €569-million will be cut from education; how, year after year, the sackings of public servants are to be done; how the plan to reduce the number of councils and shires will work; and why €890-million is to be cut from pensions.”

Louca said Socrates had a choice – he should have implemented a review of the debt and demanded its renegotiation, as proposed by economists like Paul Krugman and Nouriel Roubini. There was no other way to lift growth and employment, defend the welfare state and fund urgently needed investment in environment, agriculture, fishing and regional development.

Four Motions

On public debt, as on other issues, the convention had four positions to choose from, spelled out in resolutions (“motions”) that had been the basis for the election of delegates. Motion C, led by Portuguese followers of the International Workers’ League and representing 11.5% of conference delegates, proposed the immediate suspension of all public debt payment.

Criticising Motion A (representing the positions of the outgoing leadership and 82.5% of delegates), its supporters wrote in the Left Bloc’s discussion bulletin:

“To audit the debt without suspending payment is to cover up the problem: if we want to audit the debt it’s because it is unjust. Shall we continue to pay for an injustice? If the answer is yes, then full employment, maintaining public services and ending casualization will be little more than demagogic catchphrases.”

For Motion A supporters, it was vital that the Left Bloc’s policy could show that the government’s decision to call in the “troika” was not inevitable. Any renegotiation of the debt, including any eventual suspension of payments, could be forced on the powers of finance only if it had strong public backing. That could only be built through a public auditing of all debt – amounting to a mass education campaign – such that the Portuguese people could see where their money was going and for whose benefit they were making sacrifices.

Left Unity

Closely tied to this debate was that over how best to take steps toward the left unity needed to underpin any government of the left. For Motion C supporters, the core of the issue was an alliance with the PCP – “united the Left Bloc and the PCP could be a governmental alternative.” In debate, its supporters accused the leadership of privileging unity with left SP forces. This had ended in the “disaster” of the Left Bloc’s support for a “left” PS candidate (Manuel Alegre) in the 2010 presidential poll, who was then supported by the PS itself, putting the Left Bloc and the PS in the same camp.

Motion B supporters (1.8% of delegates) also backed the Left Bloc making a unity push toward the PCP, but to create a new left “movement-party” capable of attracting broad layers of those in the struggle – especially the young people of the “generation on the scrapheap.”

Speakers for Motion A replied that the process of left unity would never be achieved by decree or by the single tactic. For example, a Left Bloc-PCP alliance might well attract less support than if the parties ran separately: there were PCP supporters who would never vote Left Bloc and vice versa. That sentiment was reflected in Motion D (1.6% of delegates). In the words of spokeperson Jorge Ceu, it would “never envisage governmental solutions with the PCP.”

It even arose within Motion A, where an amendment stating that “the PCP does not distance itself from the Chinese CP and Cuban CP regimes and other repressive regimes,” was rejected.

Notwithstanding these tensions, the Left Bloc and the PCP recently held a leadership meeting. Miguel Portas, a Left Bloc deputy in the European Parliament, said: “The PCP and the Left Bloc have everything to gain from normalising their relationship, preventing friction and creating a non-sectarian political atmosphere.”

At this stage, the Left Bloc’s formula of a “left government” remains unavoidably abstract: it can only take clearer form on the basis of real developments, not least the results of the June 5 election and ongoing struggles against austerity.

Parliament

The other main focus of debate was over the role of the Left Bloc’s 16-strong parliamentary fraction, and a supposed lack of internal democracy and involvement by the party’s 10,000 members. The minority motions all shared this criticism. They say this is evidenced by the fact that important decisions in the life of the party (such as the decision to support Alegre and bring a no-confidence motion against Socrates), had been taken by the 16-person political commission and not the 80-person national board (the leadership elected at national conventions).

Lack of democracy was also said to be the cause of the Left Bloc’s low vote (3.1%) in the 2009 municipal elections.

These differences were laid bare in the session that considered changes to the Left Bloc’s statutes. Amendments adopted included a provision that at least 50% of the national board be composed of rank-and-file members.

A proposal to limit parliamentarians and elected public officials to two terms in office was put off to a future vote, as was a proposal to limit elected officers in the unions and social movements to three terms.

Other proposals, such as compulsory turnover on leadership bodies and easier conditions for calling special national conventions, were defeated.

When the vote on the motions was taken, Motion A had won 80.6% and Motion C 14.3%. Motions B and D and abstentions shared the rest. The incoming national board reflects these proportions.

Intensified Commitment

These debates, played out on Portuguese TV and radio and extensively covered in the print media, might suggest a party at war with itself. But that would be mistaken.

The Left Bloc’s seventh national convention was a high-energy engagement with the burning tasks of Portuguese politics, often driven by the younger generations of the party. The debate, conducted with scrupulous democracy, intensified the conviction and commitment of the delegates for the battles ahead.

When Louca delivered the convention’s closing address, a call to arms to the Left Bloc’s members to make the election campaign a battle of resistance against austerity, the hall shook with their enthusiasm. •

For further coverage of the Left Bloc conference go to www.bloco.org.