1810, 1910, 2010 and Mexican Labour

In the midst of a deep depression, an ongoing crisis of legitimacy and a brutal internal war amongst the different fractions of the drug cartel/state complex, Mexico is celebrating its two great revolutions, the Revolution of Independence (1810) and the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920).

The Revolution of Independence, which quickly took on a revolutionary popular character, was defeated — actual political independence came in 1821 as an attempt to maintain the old social regime. And the Mexican Revolution, while having a strong popular character that expressed hopes for fundamental social change, was contained within the path of capitalist development by the militant petty-bourgeois elites that provided the leadership of the triumphant currents.

Both revolutions have provided a set of revolutionary symbols, language and hopes that have not disappeared from popular consciousness. But the symbols and language that emerged from the revolutionary process came to be incorporated into the hegemonic ideology of the PRI (Institutional Revolutionary Party) regime, one committed to state-led capitalist development.

This regime of statist capitalism, which lasted for close to a century, produced an increasingly strong, concentrated Mexican bourgeoisie, a bourgeoisie that became more and more discontented with the populist flirtations of Mexican governments. Big Mexican capital, in alliance with foreign capital and international capitalist institutions, has moved Mexico from its path of statist capitalist development and “successional Bonapartism” to more direct bourgeois rule in the garb of electoral democracy.

Concessions and Capitalism at Any Price

The extent and the character of concessions made to workers and peasants varied from president to president, reaching a peak in the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas (1934-1940) when major land redistribution was carried out, the foreign-owned oil industry was nationalized, and worker and peasant organization was promoted.

In the last period of the Cárdenas presidency, however, a turn to the right, culminating in the selection of Ávila Camacho to be the next president, set Mexico on a developmental path in which there would be much more repression and many fewer concessions to the popular classes.

From 1940 on, with few exceptions, the policy of successive Mexican governments was capitalist development at any price. Trade union independence, already seriously undermined by the incorporation of unions into the ruling party as well as by repression, became even more constrained and limited to very few unions.

Trade unions became almost fully an instrument for the political advancement of their leaders and for government control over the working class. Corruption and gangsterist methods of control of unions and workers became even more common and were fostered and sustained by the government.

Though there were recurrent rank and file rebellions, union democracy and independence were definitively smashed and charrismo (authoritarian and officialist union bureaucracy), old or newly-imposed, was consolidated. Cheap wages and labour discipline was a key subsidy that the Mexican state granted to the rising bourgeoisie and played a central role in the success of Mexico’s ISI development policy, in the “Mexican Miracle.”

Behind the Mexican Miracle

The political power of Big Business grew along with its economic power during the Mexican Miracle. Business increasingly became the silent partner of government and important members of government joined the ranks of business, either openly or discreetly. The transformation of the state from a Bonapartist capitalist state toward more direct capitalist domination was well underway in the 1980s and would be intensified in the 1990s.

In 2000, the first victory of an opposition presidential candidate, the former President of Coca-Cola Mexico, Vicente Fox of the right wing National Action Party (PAN), over the ruling party’s candidate was a milestone in the legitimation and triumph of the power of Big Business, albeit in the garb of a “democratic transition.”

On June 21, 2001, President Fox (2000-2006) described his government as a “government of entrepreneurs, by entrepreneurs and for entrepreneurs” (La Prensa, Panama, June 21, 2001). The very real electoral space and democratic dynamics that were opened up were subordinated to the dynamic of the rise of more direct capitalist rule and increased repression by the state and private forces.

The concentration of wealth and power through privatization and other government policies intensified bourgeois domination, and both constrained and hollowed out the processes of democratization. When the tendencies to democratization challenge the boundaries of capitalist power, democratization is sacrificed for “stability.”

While Big Business has been able to reshape the state and public policy, it has not achieved ideological hegemony over the overwhelming majority of the popular classes, who have paid the ever-deepening costs of this transformation. Nor have Big Business and the rival political party elites been able to develop an electoral process that could legitimate the political regime.

The presidential fraud of 2006 lingers in popular memory. The smell of fraud that existed during one-party rule has now continued in the so-called “democratic transition.” The continuing fraudulent electoral processes have combined with the devastation of living standards to produce an increasingly militarized repressive state, an internal civil war, and sullen discontent.

The neoliberal assault, started in the last decades of one-party rule, has intensified since the right-wing PAN won the presidency for the first time 10 years ago. The new regime of Felipe Calderón (2006-2012) has been trying to break through the catastrophic equilibrium that has frustrated the fulfillment of the whole neoliberal agenda. The Calderón fraction is determined to complete this neoliberal transformation before the 2012 presidential elections.

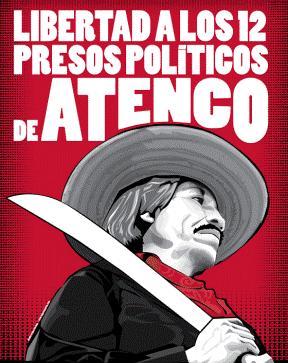

The popular forces, though suffering both small and great defeats, have been able to frustrate the capitalist offensive at times. In spite of fierce repression, the people of San Salvador Atenco, organized as the Frente de Pueblos en Defensa de la Tierra [FPDT], were able to prevent the construction of an airport on their lands outside Mexico City in the first years of the Fox presidency. As well, the government’s attempts at deepening and extending privatization of energy (exploration in deep and shallow waters for oil and gas deposits), were blocked.

The uprising of Atenco had frustrated and offended powerful interests. The airport project itself had been sponsored by the PRI-ista group of politician-capitalists, the Atlacomulco group, a group that controls the state of Mexico and is powerful nationally. The project had been approved by the outgoing PRI president, Ernesto Zedillo (1994-2000) and pushed forward by the new PAN president Fox. The FPDT had not only frustrated the airport plans of the state and powerful forces, it proudly stood as a symbol of successful rebellion and associated itself with the Zapatistas.

The uprising of Atenco had frustrated and offended powerful interests. The airport project itself had been sponsored by the PRI-ista group of politician-capitalists, the Atlacomulco group, a group that controls the state of Mexico and is powerful nationally. The project had been approved by the outgoing PRI president, Ernesto Zedillo (1994-2000) and pushed forward by the new PAN president Fox. The FPDT had not only frustrated the airport plans of the state and powerful forces, it proudly stood as a symbol of successful rebellion and associated itself with the Zapatistas.

But the PRI-PAN alliance was determined to inflict an exemplary repression on the FPDT to show that the costs of rebellion would be devastating. The PAN President, Fox, and the PRI state governor, Enrique Peña Nieto (who aspires to become President in 2012), with the active collusion of the major television channels, attacked the movement in May 2006 with a draconian use of force.

The repression was carried out by several thousand federal, state and municipal police. Over two hundred people were arrested, two killed, dozens injured, and a number of women detainees raped. Twelve activists received prison sentences ranging from 31 to 112 years. (The last of the imprisoned activists were recently released by a Supreme Court decision impugning the validity of the charges and procedures).

Assaulting the People

Later that year, after the fraudulent 2006 presidential election, the federal government carried out a brutal assault on the popular commune of Oaxaca, a movement of teachers, workers, and the community in general that had risen up against a corrupt and repressive PRI state government and controlled Oaxaca City for several months.

The Oaxaca Commune had developed remarkable popular participation. The immediate casualties of the Oaxaca repression were 20 people killed, 349 arrested and 370 injured. There were assassinations, beatings, a large number of people imprisoned, and as in the the case of Atenco, the use of torture, sexual and other.1

Both Atenco and Oaxaca exemplified the potential of popular mobilization from below challenging the neoliberal agenda and repressive state. The PRI-PAN delivered its counter-message that state terror would be used when the people interfered with the neoliberal agenda.

There have been two key objectives in the recent neoliberal assaults: 1) to expropriate and transfer public funds to private hands, involving pensions, housing and health care, and 2) to appropriate all those highly profitable natural resources without heed to the minimum requirements of environmental sustainability and industrial safety.

Popular resistance has been a recurrent obstacle. Thus these parasitical fractions of Mexican capital use their political strength to destroy those areas of worker resistance that interfere with their (ongoing) depredation of Mexico.

During the first months of his term, Calderón launched an attack on the pensions of more than two million public sector workers, whose funds had been embezzled during their shadowy management by successive federal governments since 1960.

Calderón’s proposed reforms to the laws covering the Instituto de Seguridad Social al Servicio de los Trabajadores del Estado (Institute of Social Security Services for State Workers) led to a widespread confrontation between the government and hundreds of thousands of federal and state government workers. There were national strikes and work stoppages as well as the submission of hundreds of thousands of lawsuits, and many injunctions were issued by the lower courts, challenging the constitutionality of the Calderonista legal reforms before the Supreme Court.

After more than two years of intense legal and political struggle, the Calderón regime was able to extend the retirement age for new workers as well as increasing the number of years workers were required to pay into the pension fund to qualify for a pension at retirement.

They failed, however, to extend the new measure to workers who were already under the old regulations. As well, they were defeated in their attempt to “individualize” (privatize) pension funds. The government achieved a partial victory in its attempt to reduce its labour obligations to its own workers to a minimum but was frustrated in winning its whole package.

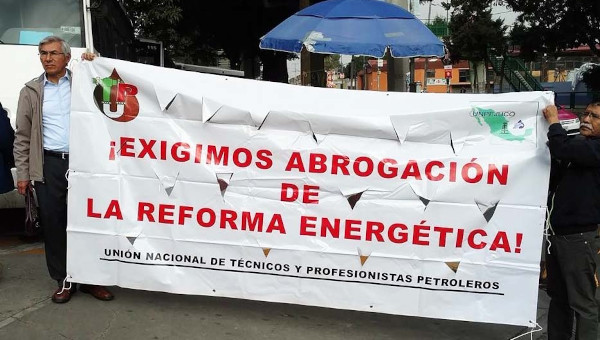

Calderón’s attempt to privatize the energy sector was even more frustrating for his government. He authorized transnational companies to start operation of wells in the deep waters of the Gulf of Mexico and gas basins in the national territory.

Such a massive project required the full denationalization of the state company PEMEX to be carried forward. But Congress, under the pressure of popular protests, only approved peripheral measures, which led to the cancellation of the deep water development, perhaps saving Mexico from an oil disaster similar to that in the Gulf of Mexico with BP.

After two partial defeats, Calderón needed a victory to fulfill some of his commitments to Big Capital, a victory that would enable him and his party to maintain credibility with the power bloc that imposed him as president in 2006. Thus the government decided to strike blows against two sectors of worker resistance that appeared to be isolated and vulnerable: the miners of Cananea and the workers of SME.2

The government showed its ruthless determination in the military and extra-legal assaults on the power workers (electricistas) and miners. On October 10, 2009, thousands of soldiers and the militarized Federal Preventive Police of Mexico, carried out a lightning assault on the electricistas and seized the facilities of the publicly-owned Luz y Fuerza del Centro (LyFC — Central Light and Power Company).

The company was liquidated in an extra-constitutional manner, 44,000 workers were fired, and the collective agreement tossed out the window. The government thus smashed a key independent and democratic union that often provided the leadership and resources for broad coalitions of resistance to neoliberalism.

At the same time, the liquidation of the company paved the way for the takeover of fiber optics for telecommunications development projects by Telefónica Española. (The Supreme Court later ratified the liquidation of Luz y Fuerza del Centro.) And on June 6, 2010, over 2000 paramilitary police seized the Cananea mine where workers had been on strike for four years.

In a juridical farce, the company claimed that the mining of copper was no longer feasible there, the Federal Junta of Conciliation and Arbitration endorsed that claim, the Supreme Court declared the decision valid and the collective agreement void and the workers without employment rights.

Soon after, the owners, Grupo Mexico, announced that they were taking actions to prepare the mine for reopening. But in spite of the Supreme Court decision and the continuing massive presence of the police, the struggle has persisted. The people of Cananea have continued to block the normalization of mine operations.

Wage Cuts and Privatization

The salaried workers of Mexico, three-quarters of the economically active population of the country, have seen their share of the gross domestic product of the country decline from 35% to 25% between 2000 and 2010.

These sharp cuts in the share of wages took place in Mexico through the tight control of charro unions over their members and their collusion in keeping wage demands low; elsewhere in Latin America, a wage drop of this proportion in the 20th century has only been possible through its imposition by the military after coups. Ironically, this dramatic decline in the wage bill portion of the GDP took place in the context of a supposed transition to democracy.

To achieve this wage contraction it was necessary for the government of the “democratic transition,” that of Vicente Fox and Felipe Calderón, to recycle and reinforce the system of control over trade unions, created by the PRI’s authoritarian governments. The preservation of the old structure of charrista control was a great benefit for the government of Vicente Fox during his six-year term (2000-2006).

With a government directly controlled by Big Business, most of the tripartite institutions, such as the Boards of Conciliation and Arbitration, the administrative council of the IMSS (Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social) and the Minimum Wage Commissions, could be used for the generalization of cutbacks and repression against workers.

Impunity for violations of labour law became more widespread. Employers have won more cases under the Federal Board of Conciliation and Arbitration than ever before. More strikes have been declared “nonexistent” (illegal) than in any other period. The presidents of many of the boards have played a biased and disastrous role against the workers, uncritically supporting arbitrary actions by the bosses. The flexibilization of layoffs has allowed companies to lay off workers without the required severance pay, relatively generous in Mexico, and has been a deterrent to workers’ protests.

The support of the old union bureaucracy was very useful in legitimating important actions and policies of President Fox’s government. As the main labour organizations were affiliated to another party, the PRI, they could present themselves as independent counterparts in the “negotiation” of state policies and present a façade of labour-government cooperation.

The new bourgeois power bloc that more directly dominated Mexico than at any time since the Revolution was content with the political rivalry between the two main parties. Both parties promoted the same neoliberal policies, albeit with different nuances and different rhetoric, while their electoral competition presented a façade of democracy.

The cases of extra-legal privatization are good examples of this cooperation. When the PAN failed in its attempt to change the Constitution to privatize electric power, it did so by stealth, under service contracts and “proyectos financiados.”

President Fox granted 211 permits for electrical power generation in this silent, extralegal manner. During his term of office, Vicente Fox inaugurated 18 new private power plants generating electricity from the northern border to the state of Yucatán. But this privatization by stealth would require the closing of old plants and the willingness of workers to accept relocation.

The old structure of labour control of the Confederation of Workers of Mexico (CTM) was essential for carrying this out. In the successive meetings held by the SUTERM (Union of Electricity Workers of the Mexican Republic, the charro union the power workers outside the central region of Mexico) with the PAN government, the union accepted the steps toward privatization.

State-Sponsored Unionism

The coalition between the Fox government and the trade union structure was essential to contain workers’ protests against the illegal processes of privatization.

The federal government and the charros needed each other, the government needed the charros to contain discontent and the charros needed the government to facilitate their dictatorships over their own members. The charros have tried to give some semblance of legitimacy to the worst infamies against Mexican workers and Mexico’s patrimony.

The replacement of the PRI federal government did not involve dismantling corporatist and authoritarian unionism. Under a supposed respect for “autonomy and independence of the unions,” the PAN gladly accepted the willingness of union leaders to maintain industrial peace and to continue their containment of workers’ discontent.

Both Secretaries of Labour during the Fox administration, Carlos Abascal Carranza for the first five years and Javier Salazar Sáenz for the last year, colluded with all of the authoritarian and undemocratic practices that PRI trade union functionaries required to recycle themselves and survive the “new times” in national political life.

Official trade unionism has been dwindling as part of the country’s economic restructuring itself. The CTM lost half of its members between 1997 and 2005.3 But its ability to deter workers’ protests remains strong, although in order to do this it has had to continue its policy of collaboration with large business groups and to expand these links to illicit activities. The union bureaucracy has recycled its modus operandi, obtaining the necessary financial resources through new activities, to maintain its hegemony in the labour market.

The PAN have tried to recreate their own corporatist social force during the ten years they have been in power, a unionism in the image of the company and/or phantom unionism and protection contracts created by the Business Right since the thirties in the city of Monterrey.

They have also sought to develop a special relationship with two charrista unions in particular: the teachers of the SNTE (National Union of Education Workers) of Elba Esther Gordillo and STPRM (Union Oil of the Mexican Republic) headed by Carlos Romero Dechamps, both of which continue to have generous contracts and to receive generous salary revisions in exchange for their complicity during the attacks on the rest of the working class, most particularly on workers in manufacturing, mining and the electrical power sector.

Two parallel processes have been taking place in the course of the two PAN presidencies. The first is a decline in the unionization rate, from a meager 12% to 9% between 2000 and 2010.

Secondly, most of the small number of “organized” workers are no longer located within the old corporatist umbrella of the Labour Congress or the Federation of State Service Workers, connected to the PRI, but in the new union bodies, the Mexican Trade Union Alliance created by the capitalists of Monterrey, and the Federation of State Employees created by the clever, predatory Elba Esther Gordillo, based on her corporatist control of the SNTE.

Attempting Accommodation

During the presidency of Vicente Fox, dissident unionism tried to redefine its relationship with the state and business by taking a cooperative approach in the restructuring of the labour process, trying to preserve, above all, their own power of bilateral negotiation. Workers in the democratic trade unions of large companies were unwilling to challenge neoliberalism, but sought to accommodate to the new situation, by creating a new equilibrium that would allow them to preserve their collective agreements and job security.

This did not mean an unwillingness to join broader political mobilizations. But it did mean that they were not in a position to be the spearhead of a major conflict with the state without risking their hopes of bilateral negotiations for their own members. Given the degradation of the conditions for labour negotiations with which they were faced, they have become very fatalistic about the real possibilities of widespread resistance. They are caught in the dilemma of trying to operate as bargaining agents in a regime determined to destroy any bargaining leverage of working people.

While union leaders of the UNT (Unión Nacional de Trabajadores — National Union of Workers) and the FSM (Frente Sindical Mexicano — Mexican Union Front) state repeatedly that they are willing to carry out a general mobilization against the neoliberal agenda, in reality their executive committees do not spend significant resources to organize the unorganized, or venture out with determination to challenge the collective agreements in the hands of spurious unionism, whether company or corporatist.

This is especially clear in the provinces. During the presidency of Vicente Fox, neither the UNT or the FSM had a strategy or a tactic to enter fully into those regions of high industrialization and low unionization — or to propose, as independent unionism did in the 1970s, the construction of a common project in strategic sectors such as auto manufacturing. Many of them are focused on very modest and immediate goals: to survive and to restore the old conditions of negotiation, but with greater transparency and integrity.

The prospects for the second half of Calderon’s six-year period are highly contradictory. On the one hand, the PAN has developed some union base, allowing an unlimited number of registrations by the Secretary of Labour to organizations close to the PAN. However, all the confrontations with segments of organized labour initiated by the government still simmer, and even the militarization of large parts of the country and the systematic use of repression seem not to have managed to intimidate the workers into submission and subjugation.

The economic situation of most Mexicans has sharply deteriorated with the U.S. economic crisis. Not only have great numbers of jobs been lost in Mexico’s maquila export sector, but the safety valve of immigration to the United States has become clogged by the sharp deterioration of the U.S. labour market. Remittances to Mexico, which have helped many communities survive, have sharply declined.

Calderón has set fire to the House of Labour, fired tens of thousands of workers, cancelled the registration and recognition of their unions, and carried out the most systematic and persistent actions to crush the resistance of workers to the neoliberal agenda in Mexico, but he has not yet gained a definitive and durable victory.

The flames in the House of Labour threaten to extend themselves, and nobody knows what the course of events will be if the regime is not able to get a clear, decisive and unequivocal victory in the coming months. One hundred years after the Mexican Revolution, there is again a great disorder under heaven, and in spite of adversity, a restless insolence permeates the streets and factories of 21st-century Mexico. •

This article first published by Against The Current.

Endnotes

- “Mexico’s Oaxaca Commune,” in Socialist Register 2008 (with Edur Velasco Arregui) (edited by Leo Panitch and Colin Leys); also available at Bullet No. 99.

- See Roman and Velasco, “Mexico: The Murder of a Union and the Rebirth of Class Struggle, Part I: The New Assault,” and “Part II: The Fightback,” November 2009.

- The number of affiliated members fell from 926,455 (Javier Aguilar, La Población Trabajadora y Sindicalizada en México en el Periodo de la Globalización.: 2001, 145) to 482,000 in 2005. (Reforma, August 7, 2005).