Britain’s Austerity Budget: A Class Act

The June Budget

Following the inconclusive outcome of the British general election on May 6th, the ‘centrist’ Liberal Democratic Party decided to turn sharply to the right by agreeing to join the Tories in a coalition government. In the run-up to the election, the Tories had argued strongly that Britain faced the prospect of a fiscal crisis unless the government’s deficit was brought down further and faster than the outgoing Labour government intended (see The Bullet no.350).

The new government quickly cranked up the volume over the deficit, with fresh scare stories about the risk of contagion from the Greek sovereign debt crisis and the subsequent disarray across the Eurozone. Although Labour and the left at once warned of the danger that sharp cuts would risk a new recession, the coalition insisted on pursuing their austerity agenda – and none more so than the Lib Dem ministers, who before the election had sided firmly with Labour on the issue.

The new government quickly cranked up the volume over the deficit, with fresh scare stories about the risk of contagion from the Greek sovereign debt crisis and the subsequent disarray across the Eurozone. Although Labour and the left at once warned of the danger that sharp cuts would risk a new recession, the coalition insisted on pursuing their austerity agenda – and none more so than the Lib Dem ministers, who before the election had sided firmly with Labour on the issue.

The Chancellor George Osborne announced the coalition’s emergency budget to the House of Commons on June 22nd. The key elements were:

- Public sector borrowing to fall from £149b in 2010-11 to £37b in 2015-16.

- Three-quarters of the reduction will come from spending cuts, and only a quarter from tax rises.

- ‘Unprotected’ areas of public spending – all bar health and aid – will face 25% cuts.

- Government capital spending (investment) to fall by 60%.

- VAT raised from 17.5% to 20% from January 2011.

It rapidly became clear what the impact of these cuts would mean:

- Forecast job cuts by 2015-6 of 600,000 in the public sector, with 700,000 further in the private sector; to be offset by 2m expected new private sector jobs.

- While the richest 10% will lose the biggest share of their income (2%), otherwise the burden will fall most heavily on the poorest, especially due to cuts in welfare.

- Postponement of many projects for renewing schools, hospitals and transport infrastructure.

The Response

Among politicians, the media and professional economists two camps immediately emerged.

On the one hand, supporters of the budget argue that the government had to announce rapid reductions in the deficit, in order to allay the concerns of the financial markets. By cutting government spending more quickly, they argue, resources of money, goods and labour will be freed up sooner to feed the expected recovery in the private sector. It will also ensure that interest rates remain low, which will stimulate borrowing by businesses. Furthermore, 77% of the projected fall in the deficit will come from spending cuts, and only 23% from tax rises; this is seen as an appropriate balance, since the spending cuts will be focused on waste and red tape, and any shift toward more tax rises would directly hit private sector spending.

The coalition’s critics disagree on all these points. The threat from the bond market has been greatly exaggerated to justify a deliberate attack on the public sector. Far from freeing resources for private sector growth, the cuts will reduce household incomes and spending, making the private sector even less likely to invest and take on new staff. A return to recession could also make the deficit even worse. What is more, the impact of the budget will fall most heavily on the poor, since higher tax allowances will not offset the effect of job losses and benefit cuts.

Key issues include the state of the bond markets; the effects of the cuts; the continued problems of the banking sector; the role of the property market; and the long-term impact on workers’ living standards.

The Bond Market Bogeymen

Despite the continuing jitters in financial markets, the Eurozone sovereign debt crisis has abated somewhat. The UK’s own sovereign debt is well outside the danger zone: there has been no difficulty in finding ready buyers for newly-issued debt, and the maturity profile – that is, the average period before the various debt issues must be repaid – remains far better than those of other countries. In addition, the extent of foreign ownership of UK government bonds (around 30%) is much lower than for other large economies (e.g. 50% for the USA). But we have to look in more detail at the global picture.

First, although it may seem paradoxical, quite a few City economists (and the IMF and the OECD) now agree with the budget’s critics, arguing that the impact of simultaneous public sector cuts across Europe and elsewhere threatens to bring the global economic recovery to a halt.1 This may well account for the worldwide slump in stock markets after the G8/G20 summit at the end of June in Toronto: the assembled leaders gave no indication of having an agreed approach, with the Obama administration apparently arguing that European deficit-cutting was too soon and too deep.

Second, too little attention is given to the global savings glut. Big non-financial businesses are awash with cash, as are the sovereign wealth funds of oil-producer states and the high-growth Asian governments, as well as the global super-rich. In the current conditions of chronic uncertainty about growth and government policies, all these types of investor are looking for safe havens, and after gold, government bonds remain the main ‘safe haven.’

The Double-Dip Risk

The critics also argue that rapid cuts in government spending will directly lead to increases in unemployment through the loss of public sector jobs. This will increase the government deficit as taxes fall and benefit payments rise; it will also hit the recovery in consumer spending, both through lower total household income and through a resulting fall in consumer confidence. Because the private sector will be hit not only by the fall in household spending, but also by the loss of sales to the public sector, they will postpone investment plans and either cut staff numbers, or at best delay hiring or re-hiring.

The coalition argues that quicker and deeper cuts in the government’s borrowing requirement will free up resources for private sector investment, and keep the cost of borrowing low. But recent surveys of business confidence in many countries show that businesses are unwilling to start investing again because of the huge uncertainties they face in terms of demand and costs. In any case, the all-important small and medium enterprises (SMEs), which are supposed to be the backbone of the recovery, are currently paying interest rates of around 10% on bank borrowing, despite the Bank of England holding its own 0.5% rate. As long as commercial banks are under pressure to build up their reserves against future losses, they are unlikely to reduce the rates they charge to the private sector.

However, it is still possible that the double-dip will be avoided. There are two reasons for this. First, despite the very slow pace of recovery, especially in terms of employment and especially in the U.S., UK and the Eurozone fringes, growth of 4-5% is currently forecast for 2010 in the world economy as a whole. China, India and other ‘emerging’ economies are forecast to acount for 70% of demand growth this year, and are now sufficiently large to have a real impact on demand for goods and services from Europe and North America. This may be sufficient to cancel out the depressing effects of public spending cuts, especially since the cuts are going to take some time to implement.

Second, while Keynesian and other critics argue that business confidence is vulnerable to fears of recession, they do not recognise that it is also boosted by any signs of continued recovery. Big businesses, especially transnationals whose production is diversified by country and product, have the cash reserves to respond quickly to market growth wherever it occurs.

The Banking Sector

The Eurozone sovereign debt crisis has brought to light the continuing fragility of many banks, especially across Europe (including the UK) and the USA. This is mainly because so many banks are holders of large amounts of government debt. The short-term response of bank regulators has been to introduce ‘stress testing’ of banks, which means examining their balance sheets to see the likely impact of events such as large-scale public debt defaults.

The longer-term response is to develop agreed rules for banking regulation across the world. This is taking much longer than originally hoped, for example at the 2008 London G20 meeting. Partly this is because of the resistance of the biggest (and therefore most powerful) banks to stricter regulation of their activities, and partly it’s because of the technical difficulties of reconciling the very different systems of regulation in different countries – even within the Eurozone countries, where the European Central Bank has to deal with 16 different national regulators.

But the real problem concerns much more fundamental issues of what we want banks to do. Most of the political centre and left held the banks responsible for the crisis right from its origins in 2007. Wanting to avoid any recurrence of the crisis, they support renewed segregation of ‘bread and butter’ banking based on deposits from and loans to households and businesses, from the ‘speculative’ activities of investment banking, referring notably to the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act in the U.S., which was repealed by the Clinton administration in 1999. There is considerable support for this move among international organizations and even bankers, but this is really only an issue for the ‘Anglo-Saxon’ economies, and for a small number of European and Japanese banks that have followed the Wall Street / City of London model. Interestingly it is strongly opposed by the government of Canada, whose large but conservative banks avoided getting involved in the more risky activities that brought down Lehman Brothers or Royal Bank of Scotland.

While these issues are still so far from resolution, banks everywhere face great uncertainty. Many continue to carry a lot of potentially ‘toxic’ lending in their balance sheets. They are urged on the one hand to build up their reserves of capital, but on the other hand to expand their lending to help the recovery, and to pay special levies to governments to provide funds which can be deployed to avoid future crises.

Property and Profits

The continued uncertainty about both the global economic recovery, and about the reform of financial sector regulation, are sufficient reason for the volatility of global bond, stock and currency markets. They also explain the tensions between the great powers, old and new, over international coordination of responses to the crisis. In these circumstances, the most likely outcome remains a drift toward ‘business as usual.’

A major part of ‘business as usual’ in the case of Britain (and the U.S., Ireland and Spain) was the boom in residential property prices in the 15 years after the end of the recession of the early 1990s. By the time the crash came, house prices in Britain were way out of line with household incomes, compared with all historical experience; while the method of financing the boom (by lenders raising money through the sale of short-dated securities) was a major factor in the 2007 credit freeze that initiated the global crisis.

A little-noticed feature of the budget is that it assumes that the recovery of house prices back toward pre-crash levels will continue. This is clear from the assumption that revenues from the stamp duty payable on house transactions will over four years recover to the pre-crash level. Yet it is hard to see how this will happen, unless the economic forces behind the boom are restored. In particular, households will have to revert to debt-fuelled property speculation, and the money markets will have to restore the flow of funds into household mortgages.

A Declaration of Class War

First of all, with regard to the effects of spending cuts, it is hard to see how the coalition can implement their pledge to maintain ‘front line services,’ since their existing commitment to level spending in some areas (particularly health) apparently means that other government departments will have to cut their spending by up to 25% (or – according to the latest leak – anything up to 40%) over the next five years. In addition, much of the supposedly dispensable ‘back room’ work is in fact absolutely necessary for the support of the front line services.

The critics argue also that the tax rises are inequitable, despite the retention of the 50% tax rate for incomes over £150,000; the VAT rise in particular is not progressive, except as a result of the fact that poor households spend a higher share of their income on zero-rated foodstuffs. Given that the impact of spending cuts, especially in benefits, will fall more heavily on poor households, the overall impact of the budget on households will favour the rich at the expense of the poor.

For Keynesian liberals and the centre-left, this makes no sense at all, because the primary need is to expand effective demand for goods and services (and thus expand employment). Poorer households are much more likely to spend their incomes, it is argued, while richer households will be concerned to reduce their debts to manageable levels.

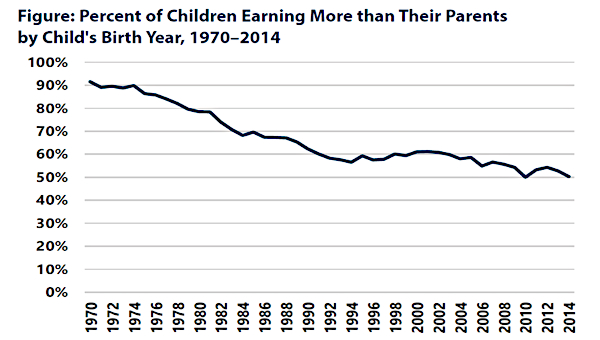

Of course, as I have already argued, businesses will only invest and grow if they anticipate growth in demand for the goods and services they produce. But the Keynesians ignore the other key objective for employers: to reduce costs, and especially labour costs, including not only wages but also the deferred wages that provide our pensions. In the U.S., the average earnings of individual workers peaked in the 1970s; in Germany there has been no wage growth in the last decade. This places strong pressure on businesses in other countries to cut labour costs in order to remain competitive.

The emergency budget includes not only the prospect of pay freezes in the public sector, but also an assault on pension costs, through raising the retirement age, raising our share of pension contributions, and tying pension levels to contribution levels rather than salaries. The message is clear: regardless of economic growth, lifetime earnings for working people are set to fall in the long term, after several generations in which rising living standards were a central feature of our acceptance of the capitalist order.

Just how important this issue is has been shown by two news items in the days since the budget. First, British Airways management’s proposed deal to settle their dispute with cabin crew includes the introduction of a two-tier workforce, with new recruits on worse pay and conditions. Second, selected Tories and their business supporters have begun to talk of the need to restrict the right to strike even further than the Thatcher legislation – none of which, incidentally, was repealed by New Labour.

We are in for a long, hard struggle – that is the clear message from this budget. •

Endnotes

- See Martin Wolf, “Demand shortfall casts doubt on early austerity,” Financial Times, 6 July 2010.