Anti-Tory Then and Anti-Tory Now

So David Cameron is Britain’s new prime minister. His accession to 10 Downing Street is reminiscent of another May election when the smug elite organized in the Conservative Party outpolled the Labour Party. May 3, 1979, Margaret Thatcher defeated James Callaghan. She would in the 1980s, partner up with her U.S. equivalent – former B-movie Hollywood actor, Ronald Reagan – the two becoming symbolic of what we now call the neoliberal revolution. Britain in the 1970s, however, did not just give the world neoliberalism. It also produced cultures of resistance. And as the election results rolled in May 6 and 7, the tunes from one part of that resistance kept coming to mind. Power in the Darkness, the Tom Robinson Band’s (TRB) breakthrough 1978 album, contained song after song which became anthems of resistance for young activists in the Thatcher/Reagan years. There are some parallels between 2010 and 1979, some important differences, and a new relevance for a thirty-two year old album.

Both 1979 and 2010 marked the end of distinct eras for the Labour Party. In 1997, 13 years before Brown’s humiliation, “New Labour” led by Tony Blair had thrown out the hated Tories, getting the support of more than 13.5 million voters in the U.K. Thirteen years later, Gordon Brown’s vote total came in almost five million votes below that figure.[1] Thirteen years of Blairism and almost a decade of war in Central Asia and the Middle East had seen a massive haemorrhaging of Labour Party support.

British Electoral Landscape

British Electoral Landscape

In the 1960s, 1970s and early 1980s, we can see some similarities. Harold Wilson had captured office in 1964 with just over 12 million votes, increasing that to 13 million in 1966. Labour did not rule without interruption in the coming years – there was the Ted Heath interregnum from 1970 to 1974 – but Labour was the dominant party during that 15-year period. When Labour lost to Thatcher in 1979, 1.5 million of those 1966 votes had melted away. By 1983, in Labour’s second loss to Thatcher, support for the party had disastrously collapsed to under 8.5 million – 3.5 million fewer than the 1966 peak. That terrible performance in the 1983 election was called a crisis for British social democracy. The sobering news for Labour supporters in 2010, is that Gordon Brown’s 8.6 million votes sit only marginally above the disastrous showing in 1983. It is in fact, a much worse showing, as there are 10 million more voters in Britain in 2010 than there were in the mid-1960s.

But if there has been a loss of millions from the base of the Labour Party, all is not well with its chief rival – the Tories. From Thatcher’s first election in 1979, until John Major’s victory in 1992, the Tories were always able to muster more than 13 million votes at the polls – in the 1992 election, the figure actually topped 14 million. David Cameron’s Tories, by comparison, did very poorly. In spite of the steep decline of Labour, they failed to win a majority, polling just over 10.5 million, well down from Thatcher-era Tory support. We gave that earlier era the nickname “Thatcherism.” As of this writing, David Cameron has a ways to go before he gets his name attached to the current political era in the U.K.

The combination of deep demoralization with Labour and an ideological assertion of free-market dogma made the 1980s a grim era for politics in Britain. But, while there are similarities, you cannot draw direct parallels with 2010. Labour’s policies have created demoralization, but the disaffection with New Labour’s pro-market policies and the long shadow of the Great Recession make a strong re-assertion of free-market dogmatism difficult indeed. The post-election landscape is much more nuanced. Among the elements of this landscape are an increased fragmentation, a marginal increase in interest in the “third party” (the actually very old Liberal-Democrats, who in spite of all the hype only received 900,000 more votes than in 2005), and a withdrawal by thousands from engagement with the electoral process. In every election from 1966 until 1997, turnout at the polls in British general elections was always above 70 percent, topping out at above 78 percent in the first election of 1974 (there were two in that turbulent year). Such figures now are a distant memory. The 1997 election was a harbinger of this, with turnout coming in at just 71 percent “the lowest for 62 years.”[2] In 2001, participation fell to just 59 percent, recovering only slightly in 2005 (61 percent) and 2010 (65 percent). The reaction by millions to having their 1997 anti-Tory hopes dashed, has been to stay away from the polls altogether.

Left of Labour

Another important element in the landscape is something that did not happen in the Thatcher era – the emergence in the 21st century of serious left electoral alternatives to Labour. Not surprisingly, this has been a difficult project. For millions of working people, supporting Labour has for generations been the only realistic means of challenging the party of the bosses. To indicate that another such alternative exists, and not just as a token, was always going to be a challenge. However mixed the record, it marks an important advance on the 1970s and 1980s.

In Scotland, it was the Scottish Socialist Party (SSP) which first gathered international attention. In 2001 it was a factor in all 72 constituencies in Scotland, averaging over 1,000 votes in each. In 2005 it did less well, but still could poll 43,514 votes in 58 constituencies – an average of 750 per candidate.

In the U.K. as a whole, the 2001 election saw the emergence of the Socialist Alliance. It stood candidates in 98 constituencies in 2001, and garnered 57,553 votes, an average of 587 per constituency. In 2005, the place of the Alliance was taken by Respect, a party deeply rooted in the mass anti-war movement of 2003 and 2004. George Galloway – exiled from New Labour because of his opposition to the war in Iraq – became the standard-bearer for the new party, and his 2005 election as a Respect candidate in the London constituency Bethnal Green and Bow was a defining moment. His 15,800 votes gave him a narrow victory over Labour – and gave the anti-war movement a voice in the House of Commons. This left-wing anti-war vote was not simply a vote for one prominent individual. Salma Yaqoob came second in her Birmingham constituency with over 10,000 votes. In total, in 26 constituencies, Respect received 68,094 votes, or an average of 2,619 per constituency.

Lost in the coverage of the 2010 election is the fact that the electoral response to these left-of-Labour forces – though fragmented into different components – was comparable to the response in 2005. The best result was achieved by Caroline Lucas, a left-wing member of the Green Party, who became that party’s first sitting MP gathering over 16,000 votes in the constituency of Brighton Pavilion. Respect was able to stand candidates in eleven constituencies winning 33,251 votes in total, averaging 3,023 votes per candidate. Galloway came third with over 8,000 votes in the London constituency of Poplar and Limehouse; Abol Miah also polled above 8,000 coming third in Galloway’s old constituency of Bethnal Green and Bow; and Yaqoob actually won 2,000 votes more than in 2005, coming in second in Birmingham Hall Green. The Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition (TUSC) stood candidates in 42 constituencies, winning 12,275 votes – an average of 292 per constituency. The SSP, while much reduced from years past, still managed to field 10 candidates, each receiving an average of 316 votes.

The attempt to build a left-of-Labour alternative takes on heightened importance when we shift our gaze to the right of the political spectrum. There is a far-right section of the British political landscape that has been steadily and stealthily making headway in the shape of the British National Party (BNP) – this decade’s organizational hiding place for the racist right in the U.K.

It is true that the BNP failed to make the breakthrough for which its more naive supporters had hoped. In the London seat of Barking, BNP leader Nick Griffin received a humiliating 18,000 fewer votes than victorious Labour Party candidate Margaret Hodge. Hodge claimed to “have not just beaten” Nick Griffin but to “have smashed the extreme right.”[3] Excellent as it is that Hodge humiliated Griffin, her analysis has to be challenged.

The BNP cannot be smashed solely through an accumulation of votes for a party which ruled in the manner Blair/Brown New Labour. As a cabinet minister in both Tony Blair’s and Gordon Brown’s cabinets, Hodge was complicit in the Blairist New Labour project. She was reported to have distanced herself from Blair’s war on Iraq in 2006, but instead of embracing that criticism and making herself part of the anti-Blair left, she insisted she had been misquoted.[4] It is impossible to “smash” the BNP while refusing to break openly from the wars which have fuelled Islamophobia – the anti-Arab racism that has made all forms of racism – and with it the BNP – a more legitimate factor in British politics.

What Hodge has to confront is that even though the BNP did not make its hoped for breakthrough, it was a visible presence across the country, winning more than half a million votes – an average of more than 2,000 per candidate – and representing by far the highest vote total achieved by the racist right in Britain in modern history. The BNP’s 2010 results are considerably up from its 192,745 votes in 2005 and 47,129 in 2001 – and higher than anything the noxious National Front (NF) (the 1970s version of the BNP) was able to achieve, the NF’s greatest success coming in 1979 when it captured 191,719 votes. Labour Party supporters need to soberly assess the fact that the high water mark for both of these far-right parties came after years of rule by Labour. The mass demoralization and fragmentation that arises from social-democratic attacks on its own base is the seed bed on which such politics can grow.

Ebbs and Flows of Class Struggle

The last and most important issue in the comparison between the two eras is inherently the most difficult properly to assess – the level of class struggle. Whereas electoral politics can be mapped through the ebbs and flows of voting results and electoral turnouts, class struggle has no such precise indicators. There is a complex relationship between ideas, organization, confidence and economic conditions which go into what Karl Marx and Frederick Engels called the motor force of history – the struggle between classes.

Without question there has been mass struggle. We have seen huge political mobilizations in Britain and around the world in the 21st century. In Britain, the most impressive of these were the mobilizations of the movement against the war in Iraq. The millions who again and again took to the streets in London, made “Hyde Park” into a verb in some quarters. To “Hyde Park” meant to oppose the war in the heart of imperialism itself.

But a demonstration is not a strike – and the beating heart of resistance to the system, which ultimately sustains all other forms of resistance, is the willingness of workers through their own organizations, to directly challenge their employers and the state. An imperfect, but indispensable, measure of this willingness, comes from the statistics on strikes and lockouts that are produced by governments everywhere. We know in North America that strike levels in the 21st century are much reduced from any of the last three decades in the 20th century. A similar situation exists in Britain.

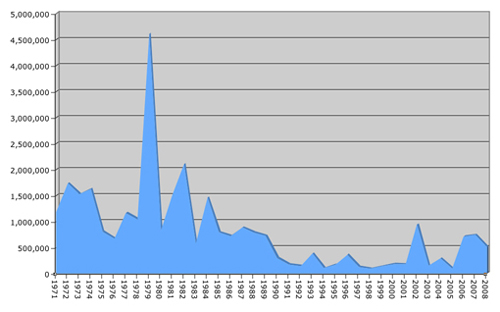

Tom Robinson anticipated something when – in 1978 – he came out with his song “Winter of ’79.” In terms of workers involved in workplace actions or strikes, the 1978-79 Winter of Discontent resulted in 1979 being the peak of the 1970’s strike wave, with some four and a half million workers during the year being involved in some kind of workplace action.[5] In the years which preceded that confrontational winter, it was a regular occurrence for there to be one million or more workers involved in strike action during any 12 month period. Those levels of activity sustained themselves through the bitter first half of the 1980s, which culminated in the great miners’ strike of 1984-1985. But from the mid-1980s through the entirety of the 1990s, strike activity was much lower than in the preceding generation.

The contrast captured in the chart presented here is striking. This century, there has been a return in some years to strike levels of the late 1980s – but nowhere near the peaks achieved in the 1970s. Throughout the entirety of the decade of the 1990s and the first eight years of the 21st century, there has not been one year where one million workers have been involved in strike activity. In many years the figure has been below 300,000; in 1998 and 2005 the figure fell below 100,000. A generation of trade unionists has grown up with much less experience on the picket line than the generation which came before.

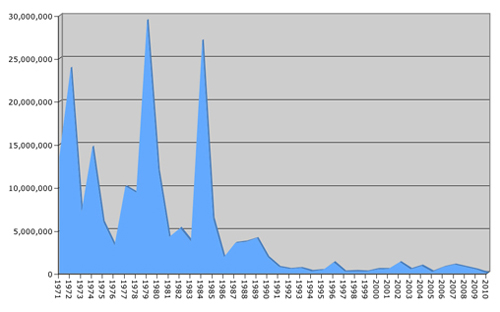

When measured as “Days not Worked” because of workplace action, the picture is even more clear. Through the 1970s and into the months of the miners’ strike, three great waves puncture the graph pictured here – with more than 20 million, and then twice between 25 and 30 million, days not worked in the course of a year because of workplace actions. However, the impact of the defeat of the miners’ strike is plain to see in the years since. Through the 1990s and into the 21st century, the number of days not worked due to workplace actions has fallen to extremely low levels when compared with the 1970s and 1980s.

The big mobilizations against the war have to be seen in this context. They were part of a magnificent political upturn by thousands who were willing to take action against traditional social democracy. But here, the analysis sketched out by the late Tony Cliff describing an earlier period, has to be taken extremely seriously. In a 1996 interview he analyzed the movement associated with Tony Benn and the Labour Party Left in the early 1980s.

“The problem was, people flocked to Benn in 1981 as a political solution when the industrial struggle was going down – but you cannot have a political upturn indefinitely at a time of industrial downturn. This expressed itself in interesting ways but the long term outcome was passivity. There was struggle in the 1980s. It was not like the 1970s but there were big struggles. The Labour left never organised centrally around them. It remained basically electoral, and that meant it was passive. If you are passive, you disintegrate. That’s why today there is demoralisation and passivity.”[6]

Cliff uses the language of an earlier generation – subsuming all workplace actions under the term “industrial” – but his analysis remains otherwise, strikingly relevant. We have seen, in Britain and elsewhere in the Global North, big political upturns associated with movements against war and against corporate globalization. But these movements have yet to find a sustained echo in the struggle between capital and labour, at least as reflected in strike statistics. If the struggle between capital and labour is the central struggle of the capitalist system, then when that level is at a low ebb, it is going to have an impact on every other form of resistance. If this is true, the decline of the anti-war movement from its heights in 2003 should not be seen as the failure of that movement, but rather understood as a reflection of the very low level of workplace struggle in society as a whole.

Understanding the class struggle context in which we are operating is important. Until it turns upwards, it will be difficult to sustain a big breakthrough to the left. We have seen recurring upswells in radicalization – in particular, against corporate globalization at the turn of the century and against war in the years that followed. But until such radicalizations gain traction and find a reflection in the economic struggle against capital, they will inevitably be prone to fragmentation and decline.

A Future Left Alternative

This is not an excuse to therefore do nothing. “If you are passive you disintegrate.” The situation in Britain will be no different in this regard, to the situation in other countries. The future left alternative to social democracy everywhere will be built from the local struggles against racism, against the cuts, against global warming, against war and imperialism – even if these struggles are happening at a lower ebb, with fewer numbers, with less generalization, and at a slower pace than we had hoped. It is in these local struggles that a new generation of anti-capitalists is finding its voice and developing capacity.

There is a final reason for taking seriously the level of class struggle. If we know that the reason we are having difficulties is not because of the personal failings of this or that individual, this or that organization, but because of the complicated circumstances in which we operate – then we will develop the patience to minimize differences and maximize unity. That unity is not an optional extra. In Britain, the wreckage left behind by 13 years of Labour in office makes plain, again, that social democracy is no alternative to capitalism. The danger of disunity is starkly revealed by the insidious presence of forces like the BNP.

TRB looked out at the landscape of the late 1970s – at the racism of the NF, at the betrayals of Labour, at the threat of the Tories, at bigotry, sexism and anti-gay politics – and sang out “We ain’t gonna take it.” It’s not a full program of resistance. It wasn’t meant to be. But it was a pretty good song, a pretty good place to start in that era, and a timely reminder of what we face today.

Prejudice poison

Polluting this land

I’m a middle-class kiddie

But I know where I stand

We got brothers in Brixton

Backs to the wall

Bigots on the backlash

Divided we fall

Women with children

Have to carry the can

Till they lose them in divorce courts

To some pig of a man

We got Benyon and Whitehouse

Trying to get us stitched

Cos abortion and a gay scene

Only meant for the rich

Sisters and brothers

What have we done

We’re fighting each other

Instead of the Front

Better get it together

Big trouble to come

And the odds are against us

About twenty to one

But we ain’t gonna take it

Ain’t gonna take it

They’re keeping us under

But we ain’t gonna take it no more [7] •

Footnotes

1.

Voting, participation and other election statistics cited in this article are compiled from: “Election 2010: National Results”;

The Electoral Commission, “Election 2005: constituencies, candidates and results,” March 2006

and “Election 2001: The Official Results,” (London: Politico’s Publishing, 2001):

“1997 General Election Result,” “General Election, 9th April 1992,”

“General Election, 11th June 1987,” “General election, 9th June 1983,” and “General Election Results 1885-1979.”

2.

“The 1997 General Election,” www.historylearningsite.co.uk.

3.

Cited in Matthew Taylor, “BNP setbacks put Nick Griffin under pressure,” www.guardian.co.uk, May 7, 2010.

4.

“Minister ‘attacks Iraq mistake’,” www.bbc.co.uk, Nov. 17, 2006.

5.

Labour dispute statistics taken from International Labour Organization, “LABORSTA Labour Statistics Database,” and Office for National Statistics, “Labour Market Statistics: Labour Disputes: Summary.”

6.

Tony Cliff, “Labour’s crisis and the revolutionary alternative,” Socialist Review 202, November 1996.

7.

Tom Robinson Band, “Ain’t Gonna Take It,” Power In The Darkness, 1978.

Other Tom Robinson Band videos: