A Real Green Deal

Thirty-five years ago, workers at the Lucas Aerospace company formulated an “alternative corporate plan” to convert military production to socially useful and environmentally desirable purposes. Hilary Wainwright and Andy Bowman consider what lessons it holds for the greening of the world economy today.

There are moments when a radical idea quickly goes mainstream. A cause for optimism but also caution; an opportunity for a practical challenge. The “Green New Deal,” a proposal for a green way out of recession, is such an idea (see interview with Green Party leader Caroline Lucas, Red Pepper, June/July 2009). It has now been adopted in some form, in theory if not in corresponding action, by governments across the world.

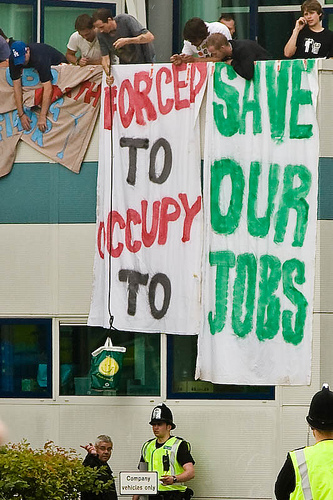

In Britain, the workers’ occupation of the Vestas wind turbine factory on the Isle of Wight – supported by green, trade union and socialist campaigners across the country – has provided a practical challenge to the government. The Vestas workers’ argument, committed as ministers say they are to green investment, is that here is an exemplary case: to intervene and save green jobs, creating a base and a beacon for further action in the same direction.

Worker occupation at the wind turbine manufacturer Vestas, Isle of Wight, UK.

Before the Vestas occupation, Ed Miliband, the minister responsible for action on climate change, made a welcome call for public pressure to achieve tougher action. But when faced with a request from the Vestas workers to talk, the government showed no interest in practical collaboration with real-life pressure – particular and complex as it invariably is. Why didn’t the government pick up on this opportunity to support a strategically-placed group of citizens who were responding to the need for everyone to take responsibility for climate change?

Strategic Choices

Was it just political caution, a wariness of giving legitimacy to a campaigning alliance that includes political forces New Labour considers beyond the pale? Or is there a deeper divide at stake? A divide between those who believe that reversing the destructive momentum of the present economy is mainly a matter of appealing to the interests of private business, cajoling them to invest in green technologies as new profit opportunities; and, on the other hand, those who believe that a green transition will at times conflict with the priority of profits and require a strong alliance with workers and citizens with the technical and social know-how and potential power to rebalance the economy with the needs of the public and the planet to the fore.

Vestas symbolises how we can’t rely on the motor forces of the capitalist market. Here were green products but low profits; hence, in a capitalist market, the result is closure and ‘rationalisation.’ How can the passions and reflections stimulated by the Vestas campaign be turned into the strategy we need for an effective and socially just green transition?

There are serious gaps in our knowledge as to how, practically speaking, a socialised green energy industry might be achieved. Vestas remains a special case – what about the polluting industries that the majority of workers are engaged in? There’s a need for some quick thinking, and the excavation of relevant lessons from the past. The words on many people’s lips are ‘Lucas Aerospace.’ They are remembering the plan for socially useful and environmentally desirable products drawn up in 1975/76 by workers facing the threat of closure in a company involved in military production. They were supported by the industry minister of the time, Tony Benn.

Meet the Shop Stewards Combine Committee

Flashback to January 1975 and a meeting of the Lucas Aerospace shop stewards combine committee. [Ed: combine committee brings together shop stewards from a number of unions in a company.] The management of Lucas Aerospace was reacting to economic crisis by cutting jobs. Listen in as 60 delegates from 13 factories discuss what is to be done at a specially-convened meeting at a stately home turned trade union education centre just outside Sheffield.

The differences between their situation and that of the Vestas workers will be obvious. They include the existence of a strong trade union organisation and some initial encouragement from a government minister – but on the other hand a green movement that was only embryonic.

Similarities emerge, however, and new insights can be gained as to how today’s green movement can make common cause with workers to redirect the economy toward sustainability without loss of livelihoods. By the end of that January weekend, the Lucas Aerospace shop stewards – a powerful mix of some of the best aerospace designers in the country, highly skilled shop floor engineers and so-called ‘unskilled’ workers with a strong class and community consciousness – had taken a pioneering decision. They decided to go back to their workplaces and involve their members in drawing up and campaigning for “an alternative corporate plan for socially useful and environmentally desirable production.”

“Let’s draw up a plan without management,” said Mike Reynolds, a shop steward from Liverpool, at this historic meeting. “Let’s start here from this combine committee. It has grown and grown. It has ability not only in industrial disputes but also to tackle wider problems. Let’s get down to working on how we’d draw up a plan, on our terms, to meet the needs of our community.”

The theme of using their skills to meet social needs – and demonstrating that their skills (used mainly to make components for military aircraft) were not redundant – was fundamental to their initiative.

“There’s talk of crisis wherever you turn,” said Mike Cooley, an inspirational designer then working at the Willesden factory (and later sacked by the company for his involvement in the combine committee), describing an aspect of the context familiar to us now. “We have to stand back … for it is the present economy that has a crisis. We don’t. We are just as skilled as we were, we can still design and produce things.”

Judging by the way that Lucas workers responded to the proposal to draw up an alternative corporate plan, Mike Cooley was voicing a widely shared ethos. The combine committee sent round a detailed questionnaire to every factory to draw up an inventory of skills and machinery and to ask fellow trade union members what they should be making. “Ideas poured in within three or four weeks,” remembers Cooley, as we talk to him about the experience nearly 35 years on. “In a short time we had 150 ideas for products which we could make with the existing machine tools and skills we had in Lucas Aerospace.”

Demonstrating Alternatives in Practice

The specific ideas are worth returning to; they illustrate in a very vivid way the principles guiding the methodology of the shop stewards – principles that continue to have relevance today. The ideas were presented as drawings and models more often than written proposals. “Can do” rather than “can analyse” was the emphasis of the combine committee. They insisted, against the conventional emphasis (including by much of the left) on linguistic skills and propositional and codified scientific knowledge, on the importance of tacit knowledge, of “things we know but cannot tell.”

This approach also illustrates the strong sense that the Lucas Aerospace workers had of the choices to be made in both the development and the application of technology. Technology is not value-neutral; it involves choices and alternative directions. “There is no single best way,” as the introduction to the plan put it.

Guided by these kinds of principles, some product ideas addressed medical needs: kidney machines for the thousands who die through lack of available equipment; a light, portable life-support system for ambulances; a simple heat exchanger and pumping system for maintaining the blood at a constant optimum temperature and flow during critical operations.

Another range of proposals concerned alternative energy sources, including proposals for storing energy produced during periods when it is not required for times when it is; solar collecting equipment for low-energy housing; a range of wind generators drawing on the workers’ know-how of aerodynamics. Others addressed the transport system and destructive nature of the automotive industry.

One proposal that was developed into a working ‘prototype,’ which they used as a form of technological agitprop, was a ‘road-rail’ vehicle capable of driving through the city on roads and then running on the national rail network, with a capability of going up much steeper inclines than normal rolling stock. Another idea involved a power pack with a small combustion engine that would enhance the efficacy of battery-driven cars, improve fuel consumption and radically reduce toxic emissions.

A final set of proposals were for tele-archic devices, which mimic the motions of a human being, in real time but at a distance. They enable workers to use and develop their skill by working with the challenges of the physical world in a way that no simple robot would be capable of – as miners, oil drillers and so on – but in a safe and secure environment.

Significantly, the plan put forward democratic alternatives in relation to the organisation of production process, as well as the end products. In emphasising the social usefulness and environmental beneficence of these products, it also challenged the imperative to accumulate and maximise profits.

Some of the products would make a profit within a capitalist market economy – some have indeed been taken up by profit-maximising companies in Japan and Germany, for example – while others would not.

Implicit was the possibility of a different notion of growth, not driven by the logic of what has been called ‘the bicycle economy’ with its driving necessity to accumulate simply to keep going.

Management’s Refusal to Negotiate

It was a radical initiative, then, but pragmatic too, drawn up to be part of the collective bargaining process with management and government. The Lucas Aerospace management danced around it but refused to negotiate seriously – because the alternative plan would have taken collective bargaining onto a level that challenged management’s sole prerogative to manage.

The combine committee initially hoped the government would engage. Talk of public ownership was in the air. In November 1974, a combine committee delegation crowded into Tony Benn’s office when he was minister for industry to discuss the future of the industry. He said he didn’t have the power to nationalise but stressed the importance of diversification and “producing our way through the slump.” It was Benn who planted the seed of the idea of an alternative corporate plan. He offered the possibility of a meeting between government, the company and the combine to discuss it (is there a lesson here for our current minister for climate change?).

By the time the plan was ready in January 1976, Harold Wilson had sacked Tony Benn from the sensitive post of industry minister in response to pressure from the Confederation of British Industry (CBI). The doors of the ministry were all but closed to the workplace trade union reps – the people who knew what could be done to produce a way out of an economic crisis and had a vested interest in seeing such plans develop.

In a sense, the alternative plan and the combine committee were a classic product of the co-operative, egalitarian creativity of the late 1960s and 1970s: challenging authority and seeking individual realisation, but through a social movement – in this instance the labour movement – and all the more potent as a result. It came up against trade union, government and management institutions stuck in the command and control mentalities of the 1950s, and the power of the movement was destroyed by Thatcher’s onslaught against the unions and radical local government in the 1980s. It could be said that the creative spirit of the 1970s got separated from the social critique and organised movements in which it was initially embedded and was appropriated by the more sophisticated sections of corporate management.

What Relevance for Today?

With the challenge of diverse social forces now coming together in search of an alternative red-green economic strategy, is this a moment when that spirit of creativity and autonomy can be recombined with the organised power of the workers and citizens struggling for democratic control over the future? What new forms could this recombination take in the 21st century, when trade unions are generally weak and the left fragmented? What new alliances could be created as consciousness of the need for a socially and environmentally responsible alternative grows?

The Lucas shop stewards showed that the most effective challenges to the dominance of the capitalist market were not abstract principles but concrete actions, the most important of which being the formulation of alternative ways of doing things. The Green New Deal comes from the same realisation, but as a response to different circumstances.

Nonetheless, with the urgency provided by climate change, the growing influence of green movements and a labour movement in need of invigoration, maybe the Lucas plan’s time really has come?

Mike Cooley points out that the subtitle of the Lucas plan was “A positive alternative to recession and redundancy.” “The underlying ideas are even more relevant now than they were 35 years ago,” he argues.

“Once again we are told that for many there is no work. Are our hospitals so well staffed and equipped, our public transport services so frequent, safe and environmentally desirable, our housing stock so adequate and well maintained that there is no work to be done? Just look around. There is work to be done on all sides. What is lacking is the imagination and courage to creatively address it.”

A renewed Green New Deal that involved such painstaking attention to grass-roots participation would be a worthy successor indeed. And, with the speed at which things are changing in environmental politics at the moment, who knows how far such radicalism might go in a few years time? •

This article first published by Red Pepper.