Against All Odds: Winning Electoral Reform in Ontario

On October 10, 2007 Ontarians will go to polls in a provincial election. But this time, in addition to casting a ballot for a politician, voters will also be asked to make a choice about the kind democratic institutions they think the province should use. On a separate referendum ballot voters will be asked whether they prefer to keep Ontario’s traditional ‘first-past-the-post’ or plurality voting system or would like to switch to the Mixed-Member Proportional (MMP) model as recommended by the Ontario Citizens’ Assembly. Depending on the commentator, a victory for MMP would mean electoral disaster or democratic renewal for the province. Yet few Ontarians seem to know what the referendum is about or why the public is being asked to vote on this issue. So far, the politicians have shied away from the debate while the media have remained largely indifferent, occasionally drawing attention to some minor implication of the proposed alternative MMP system. Even the more independent media has offered little commentary, no doubt because they are generally suspicious of elections as largely empty charades. If this continues, the whole referendum may end up falling beneath the public radar.

Electoral Reform in Historical Perspective

The upcoming referendum on the voting system may be the most important breakthrough for a more substantive democracy in Ontario’s history. To understand why, progressives have to reorient how they understand the relationship between electoral activity, institutional rules, and capitalist democracy. There is a tendency on the left to treat the institutions of the state as mere instruments of class rule, as if they were unproblematically designed and implemented to allow those with power in civil society to exercise it over the state as well. But this ignores the actual historical development of these institutions. Comparing state institutions across western countries, it is interesting how different each configuration is, reflecting the different patterns of social and political struggle within each country. Decisions over voting systems were also a part of these struggles. In fact, in most European countries around World War I, the voting system became the key front in the struggle between right and left to either limit or expand the potential of the emerging minimally democratic governments. Though contemporary Ontario is far different than World War I era Europe, the voting system referendum is nonetheless an opportunity to push the boundaries of the province’s limited democracy, if progressives take up the challenge.

The upcoming referendum on the voting system may be the most important breakthrough for a more substantive democracy in Ontario’s history. To understand why, progressives have to reorient how they understand the relationship between electoral activity, institutional rules, and capitalist democracy. There is a tendency on the left to treat the institutions of the state as mere instruments of class rule, as if they were unproblematically designed and implemented to allow those with power in civil society to exercise it over the state as well. But this ignores the actual historical development of these institutions. Comparing state institutions across western countries, it is interesting how different each configuration is, reflecting the different patterns of social and political struggle within each country. Decisions over voting systems were also a part of these struggles. In fact, in most European countries around World War I, the voting system became the key front in the struggle between right and left to either limit or expand the potential of the emerging minimally democratic governments. Though contemporary Ontario is far different than World War I era Europe, the voting system referendum is nonetheless an opportunity to push the boundaries of the province’s limited democracy, if progressives take up the challenge.

Needless to say, the governing Liberals do not see the referendum as such an opportunity. How the referendum became government policy is a complicated story but an instructive one on the state of contemporary politics. Historically, governments have maintained tight control over institutional arrangements like the voting system. Because the voting system is the link between organized political activity in parties and the exercise of state power through control of the legislature, the tendency was typically to make the rules as exclusive as possible, thus allowing only the most popular forces to gain election. This would assure that only those financed by capital would control the state. But with the rise of popular left wing parties, ones with a credible shot at gaining such exclusive state power electorally, voting system reform became a popular method of limiting their influence.

In Canada, voting system reform emerged continuously from WWI to the 1950s, whenever the electoral left appeared on the rise. For instance, BC adopted a new voting system in 1951 expressly to prevent the left CCF from gaining provincial office. More recently, voting system reform re-emerged internationally as part of struggles to either resist or entrench the neoliberal reorganization of national economies in New Zealand, Italy and Japan. Neoliberalism is also a factor in recent Canadian reform efforts, though more indirectly. Canadian governments have had less trouble restructuring the economy but the effects have led to great public dissatisfaction with the political system, and that has fuelled some of the interest in democratic reforms.

Electoral Reform Across the Country

By 2005 five of Canada’s ten provinces were considering some kind of voting system reform. In Quebec and BC, interest was partly fueled by a number of seemingly perverse elections results, ones where the second most popular party ended up gaining power, combined with a major party fearing that the rules of the electoral game might be stacked against them. In both provinces, analysts claimed that the pattern of Liberal party support meant that the party had to gain a much higher percentage of the vote than its main opposing party in order to win the election. Thus both Liberal parties were prepared to consider looking at the voting system. In the Maritimes a number of contests had returned only a marginal complement of opposition members, far fewer than their electoral support might suggest should be elected. The resulting embarrassment moved governments in PEI and New Brunswick to entrust commissions with examining the problem.

From Liberal Commitment to Liberal Reluctance

The situation in Ontario resembled both patterns in some ways. The Ontario Liberals, despite consistently being the second most popular party in the province, had seldom been in government in the postwar period. This reflected the uneven dispersion of the party’s support across the province as well as a vote-splitting problem with both the NDP and the Conservatives, depending on the region of the province. After the party’s disappointing loss to the Harris Conservatives in 1999, the Liberal leader Dalton McGuinty initiated a far-reaching policy renewal process, one plank of which involved democratic reforms.

When the Ontario Liberals won a majority of the legislative seats in the 2003 provincial election there was little blocking them from acting on their policy promises. Various aspects of their democratic reform package, like fixed election dates, were quickly introduced. But other aspects, like their promise to examine the voting system, kept missing the order paper. Midway through the government’s term in office they were still dragging their feet on the issue, while cabinet ministers and backbenchers grumbled that the whole thing was an albatross around their necks.

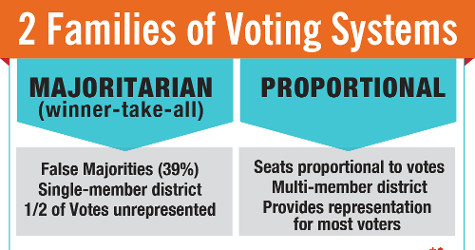

Finally, in 2006, the government established a citizen body to examine the question and make recommendations. The Ontario Citizens’ Assembly (OCA) was modeled after a similar process in BC and they came to similar conclusions – the existing plurality voting system was antiquated and undemocratic. In the spring of 2007 they recommended that Ontarians adopt a mixed-member proportional (MMP) voting system, one that would retain the traditional single member ridings but would add an additional pool of seats that could be used to bring the overall legislative results into line with the popular vote for each party. Unlike plurality, where 40% of the popular vote for a party might result in 60% of the seats or 30% of the seats, depending on the state of party competition, under MMP parties would get seats roughly equal to their voting support. Thus 40% of the votes would pretty much always result in 40% of the seats – no more, no less.

While the Liberals may be credited with (finally) honouring their pledge to allow a citizen-driven examination of the voting system, they have broken another election promise – to remain neutral about which voting system choice should triumph. In numerous ways they have tried to rig the process so as to favour keeping the plurality voting system. First, they waited far too long to establish the OCA, thus limiting the amount of time to educate the public about the issue. By the time the OCA reported their decision there was less that six months before the referendum had to be held, with most of that coinciding with the summer decline in active media coverage. Second, they lumbered the referendum with a super-majority rule to pass. Thus voters wanting change need 60% of the total votes and a majority in 60% of the ridings to displace the current plurality system. This inflates the voting power of one side in the contest and dilutes the voting power of the other, hardly a neutral decision rule. Third, they have manipulated the referendum question, shifting from a simple yes or no for the proposed new MMP system to an alleged choice between the current plurality system and the MMP alternative. Yet, as pointed out above, this choice is hardly fair when the votes for one side are plumped and the other side are diminished.

The Pressing Need for Change

Clearly, the Ontario Liberals have decided that their losing streak is over. Not surprisingly, they want to retain to retain our traditional plurality voting system, one that typically awards a legislative majority to the party with the largest minority of the vote. The point is to reduce the scope of democratic pressure to just the election day and force all the public wants into a single ‘all or nothing’ X vote. While the wealthy are free to use their resources to lobby on a myriad of issues all the time, the public are largely limited to being heard on election day, and even then can only ‘choose’ on the basis of, at best, just a few policy positions.

But it is no longer just voting system reformers who are unhappy with the present state of electoral competition. Many voters are frustrated with an electoral process where so many votes do not count toward the election of anyone, where there is constant pressure to vote ‘strategically’ (i.e. not for their first choice but for one of the top two contenders in their local area) and where governments continually promise one thing at election time but do another in office. There are also factions within all the major parties that are unhappy with the current state of things. It is often forgotten that parties are actually coalitions, ones where not all members have equal influence. Some of the push for a focus on electoral reform ® in the various parties has come from those elements that feel marginalized within their own groups, like the social conservatives on the right or the socialist caucus in the NDP.

Now that the OCA has declared against plurality and for MMP, there is some pressure for the provincial parties to clarify their positions in the coming referendum. At present, only the NDP has come out solidly in favour of the new MMP voting system. There are a few high profile Liberal supporters of MMP like Toronto-area MPPs George Smitherman and Michael Bryant but most of the government caucus is opposed or not talking. No provincial Conservatives have indicated their support but many have spoken out against any change.

Yet, as the referendum approaches, the parties have largely remained fairly quiet on the issue. The public debate, such as it is, has been mostly in hands of media and various MMP advocates. And this explains why the public knows very little about the issue: the media are not in the business of educating the public on complex matters of public policy and the MMP groups do not have the financial resources to launch the kind of media campaign to get through to voters. The challenges in such an initiative are considerable. For instance, in BC, where the voting system issue was in the public realm much longer and with more positive coverage, polling before the 2005 discovered that few knew about the referendum or understood the proposed alternative voting system. Still, in the end, nearly 60% of BC voters supported the change, largely because it had been recommended by their fellow ‘citizens’. Not surprisingly, media opponents of voting system change in Ontario learned from this experience and have expended a great deal of effort trying to discredit the legitimacy of the OCA as a proxy for the public.

To the extent that media have taken up the issue, the coverage has been slanted in favour of the status quo. A number of reporters and columnists have trotted out alarmist accounts of the instability that would result from switching from our present unrepresentative plurality system, with speculative and largely uninformed predictions of party fragmentation, the rise of single issue and extremist parties and weak and indecisive government. The fact that most western countries already use some form of proportional representation – with fairly stable results – seems lost on these commentators. Or media analysts and politicians wax romantic about how great our system of constituency representation is and how the alternative MMP system would diminish this or strengthen than hand of oligarchic parties. Never mind that few voters make their voting decision on the basis of local issues or the local member (study after study demonstrates that people vote on the basis of party, not the individual candidate or locale) and that parties are a force in all political systems, including our present one.

What might be gained from change is seldom highlighted – like accurate election results, a more competitive political environment that responds more quickly to public concerns and governments that must gain a real majority of support to push through their agendas. Those opposed to change have so far effectively managed the agenda of the public debate, focusing the public discourse on aspects of the new system that could be considered controversial (like the party control in nominating candidates for the extra pool of MPPs). In this they may have been helped by the pro-MMP forces, who decided to build their campaign around the idea that the proposed new voting system represents just a modernization of Ontario’s electoral system rather than a break with a history of undemocratic practices. The inference of the strategy is that the change is not all that major – it’s just bringing Ontario up to world standards for democratic procedures. Pro-MMP supporters, worried that Ontario voters might be less populist and anti-system than BC voters, think that an evolutionary message will get them past 60% support. But they appear to have forgotten a truism of politics: that governments are typically defeated rather than being elected. In other words, the failure of what people already know is often more persuasive than the promise of what they don’t know.

A campaign focused around the failures of the present plurality system would have accomplished a number of things. First, focusing on the system people already have some experience with would be more concrete than attempting to sell the details of a new system that people have never experienced. Second, focusing on the existing system would have highlighted aspects of its performance that most of the public is unaware of. For instance, nearly 50% of Canadians believe that legislative majority governments also enjoy a majority of the popular vote – even though almost none ever do. The last government in Ontario that had the support of over 50% of the voting public was elected in 1937. Nonetheless, most governments since then have controlled a majority of the seats in the legislature. Finally, focusing on the flaws in our current system would have focused the agenda around the issues that will be crucial in gaining 60% of the vote on election day – issues like the distorted results of our present system, the artificial barriers to political competition it raises and the role that phony majority governments play in limiting electoral accountability to voters. By their strategic choices, the reformers have taken a tough situation and arguably made it tougher.

While the odds may be against victory for MMP on October 10, success is not impossible. There is always an unpredictable aspect of politics and given that there will be a specific referendum question on the voting system, the issue may break out into the public consciousness. But for that to happen, people have to start talking about it. Progressives need to take the initiative on this by getting their networks to focus activist attention on this question of voting system reform. Though a shift to a more proportional voting system will not bring about any revolution, it will dramatically alter the space in which we fight for a more substantive form of democracy. And as Marx noted long ago, there is a radical kernel embedded within any notion of democracy – even capitalist democracy – that remains a constant threat to those with power. •

Dennis Pilon’s new book, The Politics of Voting: Reforming Canada’s Electoral System, is out now from Emond Montgomery.

Additional Coverage of Ontario Politics:

- Ontario Election section in Relay

- Ontario’s Referendum on Electoral Reform (MMP)

- Treading Water: Four Years of Ontario’s Liberals by Bryan Evans

- Socialist Project Public Forum: From Faith-Based Schools to MMP to Poverty: The Left and the Ontario Election Presentation by Bryan Evans

- Ontario and the Funding of Religious Schools by Socialist Project

- Raise the Rates: The Vital Struggle Against Ontario’s Sub-Poverty Welfare System by John Clarke