The CAW and Magna: What if Magna Builds an Assembly Plant?

In the discussions of the proposed Magna-CAW (Canadian Auto Workers) ‘Framework of Fairness’ deal, the focus has been on Magna as a components company. But what if Magna opened an assembly plant? Under the language of the ‘Framework of Fairness’, it too would be part of the deal. This might fit the union goal of adding CAW members and dues, but it might not be as welcome from the perspective of standards in the CAW Detroit Big Three plants (GM, Ford, and Chrysler).

This issue has not received much, if any, discussion but it needs to be addressed. In raising this, we do not want to suggest that the CAW negotiators might have been trying to sneak something by the members in the CAW’s assembly plants. The deal was clearly intended to be about Magna component plants, even if the language does not say so. We are, however, less sure about Magna’s intentions. This raises two questions. Is Magna likely to expand its operations into assembly? If so, how would the CAW-Magna ‘Framework of Fairness’ deal affect the Big Three?

Magna: From Parts to Assembly

Frank Stronach, the head of Magna, has long proclaimed an ambition to expand his auto components empire into car assembly for the North American market. Magna has for some time now been developing the capacity for such a breakthrough, and has been building the engineering experience for doing so through its Steyr plant in Austria, where it assembles specialty, low-volume cars on contract primarily for Daimler, but also other companies like the Saab unit of General Motors.

On August 29, 2006, a Globe and Mail story reported that the CAW was ‘offering a radical new agreement’ to Ford and that it ‘could involve Magna International Inc’. CAW President Buzz Hargrove confirmed the story and the proposed six-year agreement included a longer phase-in period for new hires (starting at 75% of the normal wage rate and getting to the full wage in six years), postponement of some time off through the life of the agreement and reductions in the number of job classifications to just two for each of production and skilled trades. This announcement came on the heels of Stronach’s earlier announcement that Magna was working on the Framework of Fairness agreement with the CAW which recently came to fruition (a similar deal is in the works with the American United Auto Workers, UAW).

Speculation about Magna’s future role as a major auto assembler took a giant leap forward in the spring of 2007, when Daimler announced its desire to sell its North American operations and Magna was, for a while, the most likely buyer. The CAW came out in strong support of Magna, arguing – in spite of Magna’s anti-union record – that ‘the union would not feel as threatened’ by a Magna takeover (Financial Post, March 31, 2007).

Daimler-Chrysler was eventually taken over by the U.S. buy-out firm Cerberus, but the saga of Magna’s possible entry into assembly did not end. On July 17, 2007 – at the very height of the negotiations over the Framework of Fairness agreement – the Financial Post reported that the CAW thought Magna was on the verge of building an assembly plant in North America and concerned that every effort be made to ensure it be built in Canada. According to CAW economist Jim Stanford, the CAW was open to ‘unique contractual provisions’ and ‘prepared to offer…a competitive and “high-performance” labour agreement to secure an investment.’ Magna did not confirm discussions with the CAW, but Mark Hogan, Magna’s International President did admit that such a factory was ‘in the offing.’ While CAW President Hargrove declared that he was ‘quite willing’ to negotiate ‘non-traditional’ labour deals when factories are built from scratch, he denied that anything was on the table at the time.

Magna Assembly and the CAW

If Magna follows through on this goal of moving into assembly, the degree of competition and uncertainty in the industry rules out Magna trying this on its own. Magna would only do so in some partnership with a major automaker; one of the global assembly companies would subcontract a particular model to Magna for final assembly.

Any such partnership would not be with the Japanese auto companies, who are doing fine as is. Nor, given their non-union workforce, do they need to subcontract assembly to escape union standards. The alliance might be with a European-based producer looking for an entry into the North American market. But in any such first entry, that producer would likely be very wary about turning its management over to someone else, especially someone themselves still in the early stages of becoming an assembler operations. Magna’s partner would, therefore, most likely be one of the Big Three. Outsourcing a new low-volume model to Magna for assembly might be a way to save on internal resources, use some of their current excess capacity for a new ‘experiment’, and involve Magna in the process of getting a lower-cost ‘non-traditional’ agreement from the union (i.e. a union that agrees to not quite act like one in compromising its workplace structures and range of potential actions).

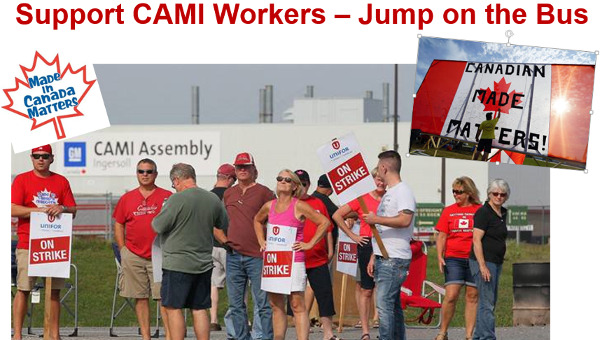

It matters very much that the partnership is most likely with one of the Big Three rather than one of the Japanese companies. This affects the likelihood of unionization. The CAW would be expected to use its existing power and influence within either of the Big Three to insist on union recognition at the new operation and a ramp-up to Big Three standards for the workers. This was a key factor in the unionization of CAMI, which was a joint venture between Suzuki and GM. The CAMI workers maintained the right to strike and the steward system and ultimately lagged behind the Big Three by only 2-3 years. (It further raises the question of why not use the union’s pressure at the Big Three to insist that any of their suppliers – like Stronach – not be allowed to deny workers their right to a free vote to choose their representatives).

This is where the Magna-CAW new

Framework of Fairness deal comes in. That deal would trump any unionization drive or alternative agreement. The agreement in the new assembly plant, if workers voted for the CAW, would come under the new Magna-CAW deal and it would be based on Magna’s company-union structure, not the CAW pattern (See Framework of Fairness agreement, p. 5, Part B, #1 and p.23, #2). The wages might be higher than in the rest of the Magna chain, but the core elements of that deal – the permanent strike ban, the absence of a steward body, and the explicit commitment to the priorities of Magna’s philosophy – would remain. (Note too that about 20% of Magna’s workforce is currently ‘temporary’ with lower wages and much lower benefits; this two-tier structure has not been mentioned in the CAW literature on the new deal, and it would presumably remain in place.)

The CAW’s ‘foot-in-the-door’ at Magna, one of the union’s main arguments in its defense of this deal, might then be the Magna Model’s ‘foot-in-the-door’ confronting Big Three workers already facing immense pressures. The implications of such a precedent, especially if it has been legitimated by the union itself, are – to put it mildly – frightening. In this light, CAW President Hargrove’s statement at a press conference that he would ‘make a similar arrangement available to General Motors or other auto makers that wanted to build a new greenfield plant in Canada’ might have been more than a verbal slip (Globe and Mail, October 15, 2007; note that Hargrove later retracted his statement according to reporters who followed it up).

If there is any validity to the above, it would also help explain one of the mysteries surrounding this deal. Why did Frank Stronach, who spent his life structuring his company to keep unions completely out, suddenly have a change of heart? Was he thinking ‘assembly’ and how to integrate the union beforehand?

A final question remains. Although Stronach – as the ‘Canadian nationalist’ – has made it clear that his preferred legacy would be to build any assembly plant for North American production in Canada, Stronach-the-businessman might in fact build it elsewhere. He may very well decide that the anti-union southern United States or third-world Mexico might be a more conducive environment for controlling workers and keeping costs down. The present value of the Canadian dollar certainly reinforces the likelihood of Stronach taking his Canadian dream elsewhere.

This exposes a further dimension of the inequality built into the new partnership with the CAW, as well as its limits. Canadian workers give up their right to refuse their labour, but Stronach maintains his right to allocate the profits he earned here as he sees fit. This applies, of course, not only to the location of a new assembly plant: it also pertains to Stronach’s continuing right to relocate any of the work under the Magna-CAW-deal.

Conclusion: Magna’s Corporatism or Union Independence?

The timing of the Magna-CAW deal and other comments surrounding it warrant some questions about the relationship between this deal, Magna’s future intentions in auto assembly, and the implications of this for Canadian jobs and standards at the Big Three. These are, of course, part of the larger set of questions that come with the current ‘experiment’ the CAW has undertaken in one of Canada’s most important industries and with the largest employer in that industry. What are the implications for the CAW as a whole, and the broader Canadian labour movement, of endorsing and then selling an agreement which includes a no-strike pledge, the abandonment of independent in-plant structures, and the embrace of Magna’s corporatist ideology?

The union movement was built by workers finding ways to organize when ‘economic logic’ suggested it was impossible. Indeed it was in the midst of the Great Depression that autoworkers first fought their way to unionization in the 1930s. Times do, of course, change. But it is in the creativity and commitment of the workers who first formed the UAW and then the CAW, and not in any return to the company unionism of the 1920s, that workers will find the inspiration to build the independent organizations they so desperately need. •