In his essay of October 17, 2016, “Big Three Bargaining: Different Ways of Making History,” Sam Gindin provides an intriguing analysis of current negotiations between Unifor and the Detroit Three automakers. Beyond agreeing with his points about tough pressure on auto workers, there is not much room for agreement on his portrayal of the issues,

the economic and industry context, or the outcomes of negotiations to-date. And there are serious factual concerns around his analysis of autoworkers’ earnings.

In the author’s effort to support a particular theoretical viewpoint about the appropriate role of unions in challenging the rights of corporations to unilaterally determine when, and where, to invest; Gindin has unfortunately side-stepped a number of major developments and events, and misstated workers’ earnings in order to portray a concessionary record of bargaining. Serious discussion and debate are essential for the trade union and other social movements, as is analysis and commentary on strategy and political orientation. In this case, however, I suggest that the analysis offered does not add up, and ultimately detracts from serious debate.

In the author’s effort to support a particular theoretical viewpoint about the appropriate role of unions in challenging the rights of corporations to unilaterally determine when, and where, to invest; Gindin has unfortunately side-stepped a number of major developments and events, and misstated workers’ earnings in order to portray a concessionary record of bargaining. Serious discussion and debate are essential for the trade union and other social movements, as is analysis and commentary on strategy and political orientation. In this case, however, I suggest that the analysis offered does not add up, and ultimately detracts from serious debate.

Specifically, I’ll offer a significantly different understanding in a number of areas, including the question of what is a two-tier system (and what isn’t); the origins and context for negotiating a wage progression; address misstatements about autoworkers’ earnings; discuss the role of unions in challenging corporations right to unilateral investment decisions; and finally, offer a few thoughts on what kind of history may indeed be made in our negotiations.

What is Two-Tier, and What Isn’t

Gindin’s analysis begins with a reference to two-tier systems as a “cancer.” On that point I wholeheartedly agree, but his portrayal of what is two-tier, and what isn’t, is sorely lacking, or perhaps purposefully misconstrued.

Organizing to overcome management’s ability to pit worker against worker, and to bring greater fairness into the workplace has taken many forms. Having two workers doing the same work, but with permanently different wages, goes against the most fundamental principles of trade unionism. The call for “equal pay for equal work” and fight against unequal treatment in the workplace date back to the earliest struggles of the labour movement. Overcoming competition among workers, and removing management’s power to play favourites, are among our most basic principles. A key mechanism through collective bargaining to counter management’s power has been to harmonize pay structures (equal pay for work of equal value), and enforcing the seniority system (neutral access to greater rights and benefits based on time in the workplace).

A real two-tier system is one in which both principles of equal pay and seniority are broken, where workers hired after a certain date receive permanently lower wages, with no mechanism or chance of ever moving up to full rates. These “bottom tier” workers will never have equal pay, and the principle of gaining rights and benefits with seniority is abandoned.

Two tier systems are well-known to divide the workforce and ruin the ability of unions to build solidarity. Gindin correctly points to the mid-1980s as a recent era of failed two-tier experiments that backfired on corporations and unions alike. Experience shows that the impact of divisions among workers, ongoing resentment, and dissatisfaction, take their toll on productivity, quality and profits. Major corporations that pushed two-tier agreements in the recessions of the early 1980s, and early 1990s, eventually saw their plans backfire and dropped them amid turmoil in the workplace (famously including American Airlines, Hughes Aircraft, General Dynamics, LTV Corporation and others).

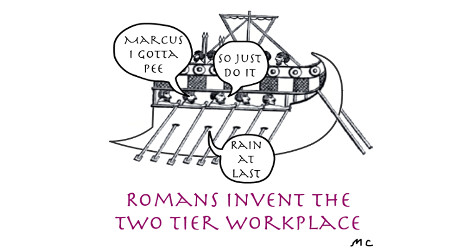

At times history refuses to be learned. The origins of two-tier systems are in fact much earlier. The first known attempt to implement two-tier wages dates back to 218 A.D., when Roman Emperor Macrinus came up with what he thought was a clever solution to address steep cost overruns in his defence budget: he decided to pay new recruits a much lower rate than his experienced soldiers. The plan turned out to be a flop: the army revolted and Macrinus was beheaded.

Those same frustrations at being permanently on the bottom played out dramatically in the last round of UAW negotiations in 2015. At Fiat-Chrysler Automobiles (FCA), the lead company in U.S. negotiations, nearly half the membership was on the bottom tier with wages starting at $15.78 and rising to a maximum of $19.28 after four years and never go any further, while traditional members were making $29 per hour. The corrosive effective of the resentment and frustrations within the workforce were well commented upon in the media, and in other analyses, prior to negotiations – and were clearly at play in the rejection of the first tentative agreement at FCA, and in the extremely low ratifications at GM (55%) and Ford (51%).

To be clear, putting new workers on the bottom with no way to get to the top is a “two-tier” system. A wage progression, however, is not a two-tier system, not at all. And portraying it as such, as Gindin does when he suggests that “everyone clearly understands it to be” a two-tier structure, is a complete misunderstanding of common practice in Canadian industry, and across the trade union movement.

A wage progression means that workers do indeed start at lower rates of pay, and then move their way up. Accruing more pay on a wage progression is already standard practice across many industries, and in many unionized workplaces, including airlines, utilities, school boards, hospitals and whole parts of the municipal public sector. Extended wage progressions are not limited to white collar jobs, (the most widely known examples include teachers and nurses, where 10-plus year wage progressions are common), but also apply to several blue collar workers. A simple review of collective agreements reveals wage progressions for photocopy operators (6 years), dog kennel assistants (6 years), liquor store clerks (7 years), electrical utility workers (9 years), flight attendants (10 years), and more.

The essential concept that rights and benefits accrue with seniority is a direct challenge to management prerogative and power. Workplaces do indeed have differences, and some things are always better, or worse, in every workplace; but seniority means there is a neutral way to gain access to benefits and rights, including job posting to preferred positions, higher levels of job security in layoff and recall, and more vacation, all in recognition of a worker’s commitment to the job, knowledge and skills.

Arguing that any wage progression whatsoever is “two-tier” would mean by definition that half of the collective agreements in the country would be “two-tier.” By that logic, the concessionary tar brush should be applied to the whole of the labour movement, not just Unifor autoworkers. But that would not support an argument that aims to single out Unifor’s wage progression as a dramatic departure and destructive concession.

Additionally, unlike so many other wage progression systems, the one expanded in Unifor’s 2012 agreement, and improved in 2016, has wages that increase automatically based on seniority, not some combination of seniority and management approval, or management’s assessment of skill and effort. Under the 2016 agreement first negotiated at GM, new workers start at $20.92 (a rate that is equivalent to the average manufacturing wage in the country), and then workers’ pay moves up automatically each year by an average of 5% over the progression, to reach $34.15. One year after workers pass through the progression, they then catch up entirely to any other negotiated wage increases and cost-of-living allowance payments that have occurred in the interim.

Keep in mind that when it comes to pay, there are dozens of ways in which workplaces, unionized or not, have all kinds of unfair and unequal pay, such as lower rates of pay for part-time workers, or lower pay for certain jobs, or lower pay for jobs traditionally occupied by women (an obvious fact given the ongoing need to redress gender discrimination through pay-equity legislation). And many of these types of unequal pay were clearly in place within the auto industry decades ago, even well after unionization, including a long-standing practice of lower rates of pay for U.S. foundry workers who were overwhelmingly black, and lower pay for trim and upholstery workers who were overwhelmingly women. In auto, these divisions were eventually overcome by harmonizing pay, and enforcing the seniority system.

A seniority-based wage progression is entirely in keeping with these principles. Is a wage progression exactly how unions would prefer that workers were paid? Likely not. I believe most trade unionists would prefer that all jobs pay $34 per hour (or more), have excellent benefits and working conditions, and a strong democratic union. But the world is not how we simply imagine it to be, and we need to organize and exercise power through our negotiations, and politically, to challenge powerful interests on the other side. As Gindin knows well, where we land in negotiations is the result of contesting power, not by imagining there is no opposing force.

As the leading argument of Gindin’s essay, a portrayal of a wage progression as something that it’s not is clearly an effort to support a his overall position that challenging corporations’ unilateral rights to determine where, and when, to invest is not the terrain for trade unions.

As important as it is to know what is two-tier, and what isn’t, we also need to understand how we ended up negotiating a wage progression in the first place. Sadly, this analysis is missing from Gindin’s essay.

How Did We Get Here?

In his discussion of how we arrived at a wage progression, Gindin’s simple assertion that “in 2012 the roof caved in on the new hire structure” portrays the development as something that just happened (likely the result, in his view, of weak union leadership). While that may be a colourful turn of phrase, it by-passes the entire context, history and developments that gave rise to the negotiation of a wage progression.

Despite selective references to the UAW throughout his essay, the analysis presented on the evolution of the wage progression in Canada neatly skips over the essential developments south of the border. While it may be hopeful to imagine what happens there doesn’t matter here, in an industry as inter-twined as auto, developments in the U.S. matter very much.

At its heart, our negotiation of an extended wage progression in 2012 was a direct result of fighting two-tier, not of accepting it. Omitted from Gindin’s analysis are the developments that brought a permanent two-tier system to the U.S. in the first place, and how those events set the stage for our 2012 negotiations.

In 1999 GM spun-off its in-house auto parts operations to create Delphi Automotive, at the time the world’s largest parts maker. Delphi followed GM in its painful downward slide during the early years of the millennium, and not surprisingly approached the UAW for major concessions, demanding that new workers cut their pay in half to about $14 per hour. Delphi won that battle. Despite the UAW’s assertion to the contrary at the time, the same two-tier structure made its way to the Detroit Three automakers during the negotiations of 2007. In the 2011 UAW agreement with the automakers, the two-tier structure was modestly improved with rates climbing from $15.78 to reach $19.28 by 2015, but critically there was still no path to full wages.

As we entered 2012 negotiations in Canada there were rapidly expanding numbers of UAW members on the “bottom tier,” with only some vague potential that after a set proportion of the workforce was on the “bottom,” then they might move people to the “top” (but that never happened in the end). In 2012 each of the companies was incredibly aggressive before, and during, our negotiations in their assertion that Canada must follow the U.S. lead on this issue and implement a permanent two-tier wage system. Frustrated with the union’s stance, their inability to achieve this concession in 2008 bargaining; and having failed again during the government-mandated cost-cutting and restructuring, they saw 2012 as their opportunity to stamp out the union’s opposition to two-tier once and for all.

A review of media coverage and the union’s official statements, during the 2012 negotiations show absolute clarity in the union’s rejection of the UAW two-tier system, and the centrality of the issue. As former President Ken Lewenza often remarked to the union’s membership, more time was spent in the 2012 auto negotiations discussing workers who were not there yet, than anything else. The negotiation of a wage progression was not about a simple “roof caving in.”

On top of side-stepping the union’s opposition to the UAW’s permanent two-tier system, Gindin critically avoids providing any explanation of the economic context that we faced in 2012. The author simply asserts that the “crisis in auto sales abruptly ended” soon after we ratified our 2012 agreement, and quickly steps over the dramatic impact of the largest financial crisis and global recession since the 1930s, and the slow recovery that continued into 2012 along with widespread uncertainty.

With a Canadian dollar at par in 2012, and companies who could hire new workers in the U.S. at $15.28 per hour (and of course could hire workers in Mexico at less than $5 per hour), the automakers insisted that unless we followed the UAW two-tier system, we would absolutely not secure any new investment.

The assessment of the union’s leadership and bargaining committees was that this was no idle threat. Having watched increasing levels of investment head to both the U.S. and Mexico, and the recent loss of thousands of Canadian jobs, the union’s strategy was to ensure that our compensation remained broadly comparable to the UAW so that Canada stayed in the ballpark for investment.

While Gindin may disagree with that assessment and strategy, he offers no analysis of the economic conditions at the time of the 2012 negotiations, and little to support any alternate view. In addition to the challenges of the immediate economic circumstances, on the policy front it had been a dozen years since the Auto Pact had been overturned by the WTO, and a half dozen years of Harper and his hostile federal government, which had little appetite to meaningfully address the ongoing crisis in Canadian manufacturing.

While Gindin admits that there are “limits to simply being stubborn,” that tactic remains as the only alternative offered, and it’s unclear how simple stubbornness would have won anything other than the most temporary gain in 2012. Certainly, the author knows that autoworkers always have some power in the short term. But investment decisions are years in the making, and while we can always hurt the companies at any given moment, they are certainly more than capable of using their power in the long-term.

In the face of these economic and political conditions, and the clear demands of the automakers, how was the union to reject the UAW permanent two-tier wage system while ensuring Canada secured future investment? The answer was to extend the wage progression, which kept workers on the path to full wages. The record of investment that followed, $3.9-billion and more than 4,000 jobs, speaks for itself. Ultimately, the Canadian example provided the path for the UAW to adopt a wage progression in an effort to change course on the existing elements of their two-tier structure.

It appears obvious to this reader that Gindin’s inaccurate portrayal of a wage progression as “two tier,” followed by side-stepping the entire context for our 2012 negotiations, is clearly designed to support a long-run narrative that the union’s leadership is weak, strategically inept, and that investment is not the terrain for negotiations. Most egregiously, however is a deliberate misrepresentation of the earnings of autoworkers.

Are Autoworkers Really Taking a 20% Cut in Earnings?

As evidence of the purportedly deep concessions the union has made, Gindin suggests “that in inflation adjusted terms, their hourly pay in the fall of 2016 was about 16% below what it was in the summer of 2008.” And in his assessment of the most recent agreement concluded at GM and FCA, he suggests that “By the agreement’s end in 2020, the loss will approach 20%.”

As a seasoned negotiator the author certainly knows this is a misstatement. What Gindin conveniently excludes in this analysis is the value of $21,000 of lump sum payments made during the course of the 2012 agreement, and that have been secured ahead in the 2016 agreement. By referring only to the “hourly wage” portion of our members’ compensation, the author deliberately discounts their true earnings. Of course, we all know that a lump sum does not add to base wages and compound in the same way as a general increase. But to simply ignore those earnings in effort to portray the agreement as concessionary is dishonest.

In the period 2008-2012 did autoworkers lose ground to inflation? Certainly. Everyone lost ground in those years. Wall Street imploded in a festival of corruption and de-regulatory government collusion, resulting in the largest global recession since the 1930s, millions of lost jobs around the world, including 235,000 Canadian manufacturing jobs, with 35,000 auto workers, or 1 out of 4, among them.

The collapse of consumer spending in the U.S., the market for 90% of Canadian-made vehicles, meant that U.S. auto sales fell by half at the depth of the crisis, and two of three domestic automakers went bankrupt. Of particular note, in the lame-duck period of the George Bush Presidency (after the election of Obama, but before he assumed office), it was Bush who unilaterally made an offer of loans to GM and Chrysler in December 2008. But as a piece of pure political payback against the UAW for its support of Obama, Bush insisted that autoworkers make steep concessions as part of the deal. Governments around the world propped up automakers during that period, but it was only in the U.S. that the offer of support included targeting workers to ensure that their very economic survival became dependent on cutting compensation. Of course, in Canada, Stephen Harper only too gladly mirrored Bush’s position.

During the negotiations that ensued with direct government oversight as a condition of public support, Canadian autoworkers were directed to reduce costs to bring them to the same level as workers in non-union automakers. Of course, during the period from 2008 to 2012 autoworkers’ wages did not keep pace with inflation. Everyone lost in that period. Average annual wage increases for manufacturing workers, where there were any at all, were tiny, averaging just 0.9% from 2009 through 2012 among unionized Ontario manufacturing workers (who earn an average of $21 per hour, not $34 as do autoworkers).

What did the union do during this period? The union fought to ensure governments stepped up to keep a specified share of North American production in Canada, made sure that jobs were saved, maintained wage rates, and pushed to ensure public funds shored-up autoworkers’ pension plans. I think the union has nothing to apologize for in its actions during that period, and to condemn the union for failing to also ensure that wages paced inflation is disingenuous at best.

And since then? In reality, over the course of the 2012 agreement, our members’ earnings outpaced inflation, and they are set to do so again in the course of the 2016 agreement. While wages were indeed frozen in the 2012 agreement, the $9,000 in lump sum payments represented $1.08 per hour in straight time earnings over the four year term. Ongoing weakness in the economy ensured a period of low inflation, and in the 12-month periods corresponding to the 2012 agreement inflation rose just 0.9% in the first year, 1.6% in the second, 1.4% in the third and again 1.4% in the fourth.

Compared to earnings in the final year of the previous agreement, the value of the lump sum payments significantly outstripped inflation in years one and two, matched inflation in year three, and meant a minor loss in the fourth year. Most critically, however, over the term of the agreement average annual earnings of Canadian autoworkers were higher than inflation by about 1% per year. In fact, the lump sums were purposely constructed to address inflation, clearly identified as such, and fully accomplished their stated purpose.

Similarly, about the 2016 agreements Gindin suggests that the “losses will now grow to 20%,” again side-stepping the lump sums, now increased to $12,000. The average $3,000 in lump sums paid in each year represent $1.44 per hour in straight-time earnings; which, along with the two 2% general wage increases, and one cost-of-living payment, will definitely outpace projected 2% annual inflation over the next four years.

In those negotiations not subject to formal oversight by government, our member’s earnings have not fallen behind inflation. To deliberately side-step $21,000 in lump sum payments to suggest that autoworkers have been subject to major concessions and that earnings are down 20% is purposely misleading, and given the author’s intimate knowledge of bargaining and compensation practices, certainly disappointing.

Did the Union Simply “tinker” with the Wage Progression?

Concerning the improvements to the wage progression negotiated in 2016, Gindin suggests that the agreement “included some tinkering,” but that doesn’t matter since a wage progression is apparently really just a two-tier system after all. As the author undoubtedly knows, a multi-year agreement can pay more money sooner (front-end loaded), or delay payment until later (back-end loaded) with major consequences for overall earnings. The 2012 wage progression was certainly more highly back-end loaded, where wages were frozen for the first three years, followed by stronger increases in the final years of the progression.

The duration of the grid is only one element of its design. The structure of when the increases occur matters a lot. What about how much money workers actually get during the course of the next agreement? On that measure, by eliminating the period where wages were frozen, and accelerating the pace of movement up the grid, workers in the progression see significant wage increases in this agreement, far outpacing inflation or what traditional members receive.

Consider that a member with two years’ seniority saw their hourly wages rise from $20.49 to $22.80 immediately on ratification of the agreement, an 11% wage increase. The following year that members’ wages will grow to $24.59, another 8% increase; the next year wages will grow another 6%, then a further 5% in the final year. This member’s hourly earnings will increase by 33% over the course of the agreement.

Critically, these increases are not all about just climbing up the wage progression anyway. The steps of the wage progression were significantly increased, particularly in the earlier years. Compared to earnings under the previous wage progression, the pay rates that a member with two years’ seniority will have over the next four years were increased in the 2016 agreement by an average of 10% on each step. Those improvements alone will result in $21,050 more in straight-time pay during the agreement than they would have seen otherwise. And on top of these gains, this member will receive $12,000 in lump sum payments. Portraying these levels of pay increase as “concessionary” is well beyond credibility.

In what can only be an effort at humour, the author suggests that the union has effectively stolen $200,000 from new workers because conditions today are not the same as they were in 2008, and our negotiated improvements are akin to stealing their cars and giving them back a “fiver for coffee and bus fare.” The essential point missed is that that under the conditions in 2008 there were absolutely no new hires, not back then, and there would not be any now. To continue with the analogy, there simply would be no new members from which to steal cars and give them back a “fiver.”

Not surprisingly, what is missing from Gindin’s positive assessment of the UAW’s supposedly superior 8-year wage progression is an acknowledgement that UAW wages start $4 per hour lower, and end $5 per hour lower, than on Unifor’s wage progression. He also incorrectly suggests that the UAW moved “from a 10-year grow-in to an 8-year grow-in, “although they never had a 10-year grow-in in the UAW, rather until 2015 they had a permanent two-tier system. Even more importantly, the author ignores in his observations about the UAW agreement the fact that the companies have little intention of ever directly hiring onto their new progression, as they have dramatically expanded access to part-time workers who will continue to start at $15.78 per hour an reach a maximum of $19.28 after four years’ service with no path to full wages. Despite many important gains in their 2015 negotiations, clearly there is more work to do to fully eliminate the permanent two-tier system. The companies’ clear intention is that future new hires will spend a few years as temporary workers, and only then would they be considered for placement at the start of the wage progression, effectively making it a 10-year system, or longer.

Ultimately, in his criticism of the wage progression and overall wage negotiations, it would appear that the author would simply wish away NAFTA, the overturning of the Auto Pact, the global financial crisis and recession, the automotive bankruptcies, the government-mandated cost reductions, a decade of Stephen Harper, and the existence of the UAW’s true two-tier system. And by wishing these developments away, and offering miscalculations, only then can he suggest that the strong improvements in earnings negotiated for in-progression members were not improvements at all, but were really about “consolidating concessions.”

What About the Defined-Contribution Pension?

Gindin offers some room to acknowledge that the union “does raise some legitimate questions of whether private companies can in fact guarantee defined benefits in the future.” But then quickly dismisses the union’s adoption of a defined-contribution plan for new hires as a “betrayal.” Missing from his observations are the scale of the challenges faced by defined-benefit plans. In an era of incredibly low interest rates (fuelled by failing monetary policy supposedly designed to address structural failures of global capitalism), defined-benefit plans must put away dramatically more money now to pay for future benefits. In fact, the Detroit Three will put $1.3-billion per year into their Canadian plans during this agreement, far outstripping the investment commitments secured to-date.

The author does suggest that a radical transformation of universal public pensions is in order, and on that front I would agree. It is this understanding that lay behind the labour movements’ successful push for the expansion of the Canada Pension Plan. But to single out Unifor autoworkers as “betrayers” is a dramatic overstatement. We have, and will continue to, defend defined-benefit plans across our union, including the maintenance of the existing defined-benefit plans in auto. Criticism of the adoption of a defined-contribution plan for future hires in our 2016 bargaining is like attacking one of the last soldiers standing, and ignoring all the rest who have fled, or been forced, into a similar position earlier (including the UAW in the Detroit Three in back in 2007, and other major Canadian employers such as Vale Inco, U.S. Steel, Toyota and the Royal Bank, among many others).

Moving forward, new hires in the Detroit Three will have a solid defined contribution plan, where the employer will pay a minimum of 4% of earnings, and up to 6% if members elect to contribute 1% more. Given the timescale involved for future new hires, the enhanced CPP will be in force by the time they retire, and the union will certainly fight for further expansions of universal programs like the Old Age Security, and further strengthening of the CPP. The author acknowledges that the pension challenge is indeed larger than any one union, and one company, can fully address in all sectors in all occasions. However, when the author advances this acknowledgement it is presented as insightful analysis, when the union does so it is a “betrayal.”

The Investment Trap?

Beyond the selective history and miscalculations, the most troubling element of Gindin’s essay is the very reason to employ such artifices in the first place: to support his argument that workers should not even contemplate directly challenging capital’s right to unilaterally decide where, and when, to invest. As Gindin lamely suggests, insisting on investment “moves bargaining into the terrain where corporations call the shots.” Where don’t corporations call the shots? The clear assertion is that unions should know their rightful place, and not challenge that power.

It’s fine, in the author’s eyes, if unions join in a “political struggle” around investment, certainly to be guided by outside political experts. But to directly use the union’s own power to challenge corporations’ right to close factories and eliminate jobs apparently is heresy. In previous writing on our 2016 negotiations Gindin’s core argument means that the union should not have even tried to stop the closure of GM Oshawa, or fight for the future of workers at FCA Brampton or at Ford Windsor. Perhaps the union should have just stood back and hoped someone else would step forward to take care of it? Or perhaps, fatalistically, the union should have just let the workplaces close, somehow spurring workers into apparently deeper political action for greater long-term gain?

It’s fine, in the author’s eyes, if unions join in a “political struggle” around investment, certainly to be guided by outside political experts. But to directly use the union’s own power to challenge corporations’ right to close factories and eliminate jobs apparently is heresy. In previous writing on our 2016 negotiations Gindin’s core argument means that the union should not have even tried to stop the closure of GM Oshawa, or fight for the future of workers at FCA Brampton or at Ford Windsor. Perhaps the union should have just stood back and hoped someone else would step forward to take care of it? Or perhaps, fatalistically, the union should have just let the workplaces close, somehow spurring workers into apparently deeper political action for greater long-term gain?

Certainly, much stronger state power mobilized in the interests of economic development and good jobs would be welcome. But absent that just yet, workers must do what is within their power: including making absolutely clear to the corporations that we do not accept their unilateral right to close productive workplaces and eliminate jobs.

In Gindin’s analysis, taking this stand and mobilizing members and communities behind the seemingly audacious demand, succeeding in reversing a planned closure and securing nearly $900-million in new investments to-date, while simultaneously delivering strong economic improvements to all members, cannot be truly a win for workers and the union. It must indeed be a trap. And in an effort to prove his theory, the author is willing to pull out all the stops to concoct concessions that don’t exist.

What Kind of History is Being Made?

Do corporations continue to have too much power in society? Absolutely. Have economic and political conditions of the last three decades weakened autoworkers, and indeed all workers in Canada? Yes again. Are many workers frustrated these days? No doubt. Is there need for stronger renewal of the labour movement and all progressive movements? Certainly. On all these questions I believe the author would agree. But to address Gindin’s core argument: Can unions directly challenge corporations’ right to unilaterally decide when and where to invest, and make gains for members at the same time? The answer from our 2016 negotiations is clearly yes.

Of course there are limits to union power, requiring the ongoing building toward wider political movements; and there are few, if any, complete victories; but those are indeed the great lessons of the labour and social movements. After bestowing his confirmation of the “end of the union’s leadership legacy within the labour and social movements,” Gindin wonders aloud about the kind of history being made in these negotiations. He suggests that only a rejection of the pattern agreement at Ford has the potential to set the union and the labour movement in the right direction.

There remains, however, the troubling fact of democracy to address, and about which Gindin remains silent. Underlying the author’s views, of course, is an inescapable assertion that workers are easily swayed and ultimately incapable of using their own intelligence and experience to analyse the situation, and make their own decisions. In particular, given his scathing condemnation of the recent agreements as entirely contrary to workers’ interests, the author can only believe that the 4,000 workers at GM, and nearly 10,000 at FCA, must be incapable of democratically electing their own bargaining committees who negotiated the agreement; incapable of intelligently understanding and endorsing their demands by democratic vote; incapable of democratically providing their committees with a strike mandate; and ultimately incapable of properly analysing the settlement and then overwhelmingly ratifying the agreements by secret ballot vote. Surely, in this view, these workers must be pawns in need of better leadership.

If there is history to be made in these negotiations, perhaps it is in these moments where we can relegate to history the kind of politics that argues up is down, and left is right, only to satisfy a theoretical argument that has been disproven by evident facts. Workers can use their power to directly challenge corporations to make investments, while at the same time make gains for all members and build the union: Unifor just did.

The militant demand that Unifor has advanced in these negotiations offers a challenge to the fundamental terrain of corporate power through mobilizing members to strike for investment, and should be applauded by progressives and seen for what it is: a victory for autoworkers and a basis for further mobilization. Ultimately, I remain convinced that workers know what they’re doing. •