GM, the Delphi Concessions and North American Workers: Round Two?

It is important to recall that until the 1970s, collective bargaining in the United States and Canada was largely about workers demanding improvements from their employers. But a new era in collective bargaining erupted at the end of the 1970s that was soon dubbed ‘concessionary bargaining’. Corporations were now the ones making the demands. Tensions had been building through the decade, with corporations increasingly asserting that they could no longer both maintain profit rates and meet workers’ demands and expectations. Governments also intervened to shift and enforce the balance of power in society through ‘neoliberalism’ through the 1980s, transforming the policy ‘rules of the game’.

We are about to see the second wave of this attack on the North American working class. The first wave did not, of course, ever subside: the story of the past quarter century is a litany of increased pressure on the job, insecurity over keeping decent jobs, longer hours and increased debt to hang on to consumption standards, concern over social services, growing inequality, and the weakening of trade unions. This is all about to get dramatically worse.

We are about to see the second wave of this attack on the North American working class. The first wave did not, of course, ever subside: the story of the past quarter century is a litany of increased pressure on the job, insecurity over keeping decent jobs, longer hours and increased debt to hang on to consumption standards, concern over social services, growing inequality, and the weakening of trade unions. This is all about to get dramatically worse.

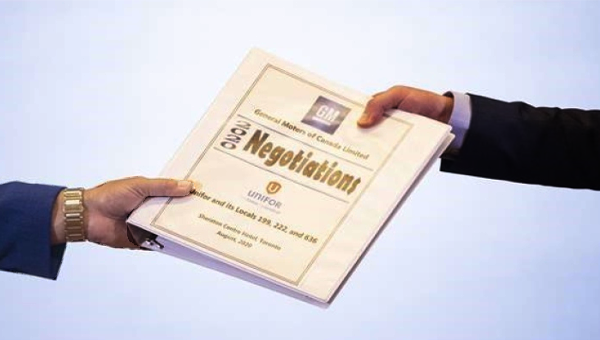

The events signalling this second wave are unfolding in the American auto industry. The United Auto Workers (UAW), under threat from General Motors (GM), opened its collective agreement to save GM over $1 billion in health care costs. UAW is currently in negotiations at Delphi (a components division spun off from GM in 1999) where the corporation is threatening to go bankrupt if workers don’t cut their wages to $10/hr from the current $26/hour as well as surrender health benefits and more or less reduce the union to a dues collection agency that overseas a non-union workplace.

None of this is entirely new: American (and to a lesser extent Canadian) workers in the airline and steel sectors are all too familiar with concessions linked to corporate restructurings from bankruptcy. But given the pattern-setting role that the auto sector has always played, the impact of these latest developments should not be underestimated. And given that the US-Canadian auto industry is the most integrated cross-border industry anywhere in the world, workers on the Canadian side of the border will not be immune from the concessions pressures.

Several key questions emerge. Will this be just an isolated bad-news story – a tsunami-warning – that we can only hope misses us or at least doesn’t do any damage? Or will it be a wake-up call warning us that if you’re not fighting back, you’re only waiting for things to get worse? Is what’s coming inevitable or can it be resisted? The first concessions wave led the Canadian Auto Workers (CAW) in a direction that challenged neoliberalism, free trade and ultimately their UAW parent union. What will the CAW response be this time?

Any effective counter-response will demand some creativity on the part of workers and their unions, and a crucial beginning is that workers in the U.S. and Canada start talking about why this is happening and what might be done. The following points, we hope, might contribute to the discussion of what an anti-concessions campaign must take up.

1. You can not privatize the welfare state.

The first generation of postwar autoworkers used the good times to achieve a host of social benefits, health care and pensions being the most important. But in bad times, and especially when the competition didn’t carry the same costs, those benefits came under attack. Defending them in bargaining had its limits both because the companies were in trouble and because winning benefits which other workers did not have left autoworkers relatively isolated.

The response to the recent GM attack on the health care benefits of autoworkers should have been – as some American rank-and-file workers insisted – to call for a national health care program that extended this crucial benefit to everyone, not taking it away from those happened to have some protection. The UAW did eventually make this point, but only after they had made the concessions on cutting healthcare costs for the company. Had they challenged GM and put the larger issue on the national agenda, the union might have been a catalyst for a larger struggle (and for taking a step towards reviving the potential social leadership role of unions more generally). But declaring this only after the precedent that UAW workers would bear the costs of cutbacks was set reduced the UAW statement to empty rhetoric.

For Canadian workers, this may seem beside the point, as Canada already has a national health care plan. But isn’t that health care system now under attack? And if this leads to having to negotiate an increasing share of health care privately with companies, what would happen to the CAW’s ability to negotiate wages and other benefits? More important, however, is a larger lesson from the UAW concessions: workers and unions who get too far ahead of other workers when the situation favours them, will inevitably get in trouble when the winds change. Workers in leading sectors will eventually be dragged down if other workers are being pushed to the margins. Progress for workers has to be generalized or those gains will be vulnerable to reversal.

2. The problem isn’t ‘out there’ from globalization, it is in North America.

The main problem that the GM and Delphi workers face isn’t competition from China or Mexico or even Japan but issues which can be directly addressed at home. As Steve Miller, the head of Delphi said in a recent speech: “…in the auto industry, Toyota, Nissan, and Honda are competing from assembly plants in our back yard…the old oligopoly has crumbled, not so much from globalization, but from upstart domestic competition” (October 28, 2005). In the parts sector, 80% of the U.S. industry is non-union and many of these plants pay less than half the wages at Delphi (non-union parts also increase the incentive to outsource even more from the assembly plants).

The issue is not so different in Canada where the overall industry is in fact doing well, but non-union auto majors are winning a larger share of the market. Here too Toyota and Honda won’t be organized through business as usual and neither will the parts industry, where the level of unionization was once close to 80% and is now approaching 40%. Unless the CAW shows the same verve which unions showed in the 1930s when they were able to organize workers in spite of times much tougher than today (and in spite of dramatically fewer resources than today’s unions), breakthroughs in unionization simply won’t happen. In the 1930s, for example, mineworkers sent 100 organizers to organize steel workers so miners would not be isolated.

Although the auto companies are global, production is overwhelmingly regional: cars sold in North America are largely assembled in North America and made of parts produced here. This makes organizing all the more possible, especially if it is seen in cross-border terms. Why couldn’t the CAW and UAW, for example, jointly declare: that the 10 major parts plants will be organized; that the longer it takes, the more disruption the entire industry will face; and that there is no point moving form the U.S. to Canada or vice-versa because we will be there to organize (and into Mexico as well)? And why would the UAW not put US$200-million of its ever increasing and unused $900-million strike fund to such use, if only to defend its own members?

3. Opposition to free trade is nevertheless necessary.

Blaming globalization and free trade for everything can be a diversion from more basic issues. Yet corporate mobility does remain a threat and this will increase as we escalate our fights. If we see the issue not as other workers taking our jobs, but as the freedom of corporations to do what they want with production versus the ability of workers to influence their lives and communities, then fighting free trade is a matter of democracy (workers’ freedom versus corporate freedoms), of joining with other in the community to fight the unilateral power of corporations, and of international solidarity to avoid the ratcheting down all global working standards.

To limit corporate threats of shutting down plants, it makes sense to revive a variant of the former Canada-U.S. auto pact and use the leverage of the market to assert that investing in North America is a condition for making profits here. Such a pact to constrain corporations and gain some controls over investment flows would necessarily be extended to include Mexico and Mexican workers. This couldn’t be done alone: it would mean a commitment on the part of unions far beyond anything to date to join the global justice movement. In turn, such a campaign might offer the wider movement the kind of concrete example it needs of alternatives to free or simply fairer trade in favour of planned trade.

4. There is a need to question what we produce.

The big ‘no-no’ within auto unions in North America is questioning what kind of products workers are making. This was not always the case. In the early 1950s, the UAW was a national leader in calling for small but safe, fuel-efficient vehicles. Leaving this decision to the companies has neither helped auto workers nor consumers. Time and again, the companies gave up on this less-profitable part of the market to concentrate on higher-profit big vehicles only to see its competitors use this as a base for taking market share. Now, an important part of the problems at the Big Three of GM, Ford and Chrysler are not only cost but the product. Where are autoworkers on this issue today?

The issue has been avoided in part because of the belief that the companies know best and in part because any criticism might hurt sales and therefore the jobs people depend on. The problem is that whether or not the companies know what their doing in terms of their own interest, there is no reason to think it coincides with the collective interest of auto workers or workers more generally. And had we been pushing for vehicles (and an entire transport policy) more sensitive to environmental concerns – as we were warned to do by environmentalists pointing to the trajectory of global warming and the inevitability of rising gas prices – auto and transport sector jobs might actually be more secure today.

Consider one example. The Ford engine plant in Windsor makes large engines. It has been clear for some time that this could not last. Why is the union not out front mobilizing publicly for Ford to move to develop new kinds of engines, to convert the Windsor facility to produce them, and to make any monies given to Ford by the Canadian and provincial government conditional on such changes? This may not offer immediate answers to those laid-off, but it would position the union, both in the community and nationally, as leading on a social issue and this would be part of developing the capacity to perhaps influence the direction of Ford and positively affect jobs down the road.

5. There is space to negotiate decent contracts.

It needs to be pointed out that the auto industry is not leaving North America but competing to come in. Overcapacity is more of an issue than plants leaving.

In Canada, because of the $0.85 dollar (in terms of the US$) and health care costs, workers in the Big Three continue to have space to negotiate decent contracts. AS the CAW pointed out in a recent presentation, Canadian Big three workers are $10 per hour cheaper (or $20 thousand per worker yearly) than in the USA. It is true that Canadian parts workers must confront the falling level of unionization in both Canada and the US. But much of the low-wage, low-capital section of the Canadian industry departed in the 1980s, leaving an industry that is mid to high tech in value-added and quality-based. This sector has the advantage that it is not as easily moved, and that it must be located close to just-in-time assembly plants. Of all the vehicles assembled in North American, 1 in 6 are assembled in southern Ontario, with a huge parts industry therefore arrayed around Ontario as well.

A crucial question, however, is what to focus on in bargaining. Working time stands out for three powerful reasons. First, it is quite amazing that while productivity has been growing (output per hour has doubled since the first wave of concessions in the 1980s), workers are left with less and less of their own time. Second, while higher wages in the Big Three increase the gap with other workers, more time off is solidaristic in terms of sharing existing jobs. Third, and this is especially important in the USA, the attempt to limit the impact of job loss through income security and higher pensions has increased costs for the Big Three in a way that disadvantages them relative to non-union assembly plants. But paid time off is something the non-union plants tend to follow to avoid unionization (or at least it can become a major issue in organizing). So negotiating paid time off is actually a better response even from the narrow perspective of ‘competitiveness’.

The time to negotiate paid time off may not be only when things are going well. It may be that this is more likely to be achieved when there are layoffs and the issue is solidarity to limit the layoffs (the original UAW Ford contract in the 1940s provided for going to 32 hour weeks before layoffs took place, a reflection of the solidaristic culture then). Solidarity may also be invoked to limit overtime when some are called back and many remain off work. In most cases, the company will plan to reduce the workforce even when the upturn comes and so limiting overtime might become a permanent union policy.

6. Militancy is not enough.

Worker militancy is fundamental to everything else. If there no struggle over everyday issues and wages and benefits, there is unlikely to be struggles over anything. Parts workers do have power – in some ways even more power than workers in assembly – because they can shut down a significant range of assembly plants.

But militancy itself comes up against barriers that are real and not just propaganda: non-union plants, products that are not selling, corporations threatening to move abroad. Sometimes this demands new strategies. For example, if one plant is constantly disrupting overall production, the companies may move it. But if disruptions are strategically spread across various plants at different times, no one plant can be targeted by the companies.

This strategy, too, will come up against limits. The key is that when workers come up against a wall in fighting back, the question must not be how to retreat but how to knock down that wall or how to scale it. That is when we have to go beyond the everyday role of the union and raise larger issues, deepen the involvement of the members, and build broader class and social alliances.

7. A rethinking of unions is needed.

A common thread running through all of this statement is that: (a) in fighting concessions and building unions, the need is to act now, and not wait for further initiatives from the corporations; and (b) the constant importance of building the capacity of workers to respond so we can, in fact, have more meaningful options in the future. Over the past almost thirty years of neoliberalism, corporations and the economy have gone through remarkable transformations. Unions too have changed, but not always in positive ways and not always in ways adequate to taking on the new economic and political challenges. It is therefore central to any successful working class response that workers think about their unions and ask how they too might be transformed. This is the difficult but increasingly unavoidable question that workers and unionists, and socialists and the Left more generally, cannot avoid. •

Other Resources on Delphi and the ‘New Concessions’

- The Delphi concessions can be found at www.detnews.com/2005/autosinsider/0511/02/A01-369555.htm.

- An important statement on the fightback to the Delphi concessions can be found at the UAW New Directions Movement web-site at www.uawndm.org/uawndm/retire.htm.

- A ‘Hold Delphi Accountable’ petition on the Delphi bankruptcy

proceedings can be signed at www.thepetitionsite.com/takeaction/570770279?ltl=1131905012 - For a discussion of an alternate North American auto industry, addressed to American, Canadian, and Mexican auto workers, see the Socialist Project pamphlet on the auto industry: ‘Concretizing Working Class Solidarity: International Solidarity beyond Slogans’ at socialistproject.ca.

- For a list of resources and labour reform groups in the U.S. go to:

www.uniondemocracy.com/AUDLinks/RNFLinks.htm.