Spain: A Spiral of Crisis, Cuts and Indignacion

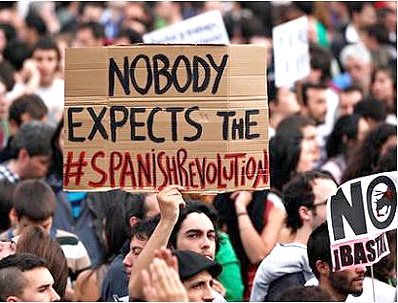

In March 2011 several regular Guardian columnists analysed the crisis in the Spanish state and the response to “austerity” by the population. All agreed that young people were “apathetic” and even “docile.” Two months later that same youth led tens of thousands to occupy city squares and a million to demonstrate across the country – the movement of “the outraged” (los indignados in Spanish). Actually the journalists were not wholly wrong: at the time of writing there had been a limited fightback and the consensus across Spain was that people were apathetic.

The immediate cause of the current global crisis was generalized property and financial bubbles in the developed world. Spain was an extreme case of this, with a million housing start-ups taking place in 2007 (more than in Britain, France and Germany combined). This generated massive profits for construction companies and banks which invested heavily internationally (including buying airports and high street banks in Britain). Rising house prices fuelled consumer spending, while half of the jobs then being created in the EU were in the Spanish state.

When this mega-bubble burst – coinciding with the international credit freeze, building literally stopped overnight. In December 2008 only one single house was built in the whole of Spain! Loans of hundreds of billions of euros by regional banks (known as ‘cajas’) to estate agents and construction firms turned ‘bad’ and, when recession led to mass unemployment, the banks cruelly evicted hundreds of thousands from their homes leaving them with a mountain of properties they would never sell.

Financial Black Holes

The Socialist Party (PSOE) and right wing Popular Party (PP) governments have been slow to intervene in the cajas because their managements are corruptly appointed by those very parties. Bankia, whose gigantic toxic loans eventually led it to be part-nationalized last month, was headed by Rodrigo Rato, a former deputy prime minister in a PP government and a regional-government appointee.

The financial ‘black holes’ caused by the housing collapse have depressed the rest of the economy and weakened public finances, helping double the interest Spain has to pay on its public debt. This situation has been made far worse by savage government cuts. Austerity was first introduced under the PSOE administration of Zapatero which raised the pension age and reformed the constitution with the PP to hinder future governments from borrowing to pay for services. In the autumn elections last year the PSOE was unceremoniously sacked when four million of its mainly working-class voters stopped backing it.

Since the victory of the PP under Mariano Rajoy such adjustments have been relentless. Labour ‘reforms’ have slashed protection against both dismissal (an important ‘safety net’ in the absence of long-term unemployment benefit) and arbitrary lowering of wages. This year’s education budget was slashed by 22 per cent and tuition fees were increased by 66 per cent. As part of a vile attempt to blame immigrants for the crisis, hospitals have been ordered to refuse to attend to undocumented foreigners (although many health workers are refusing to comply with this).

One factor behind this savagery is the attempt by the right to apply what Naomi Klein termed a “shock doctrine.” This refers to the way neoliberals profit from the stress and disorientation caused by economic crises to break up welfare systems and introduce pro-business policies. Before the London riots Rajoy held up David Cameron‘s programme as a model.

There also is a European element to the government’s offensive. After the disastrous bailouts in Greece, and with the larger Spanish and Italian economies headed for a similar ‘rescue,’ the European Central Bank created a one trillion euro fund for beleaguered European banks. Most of its first loans went to Spanish banks who then re-lent it to the government! Such indirect bailouts come with the compulsory strings attached: a limiting of budget deficits (in the Spanish case to 5.3 per cent). This requires cutting the deficit by 3.4 per cent in a year, which would require a historic level of cuts. Rajoy has announced there will be a new ‘reform’ every Friday.

As well as creating great suffering, the EU and Rajoy are pushing the economy into a depression. Unemployment has continued to climb, with a further 700,000 jobs lost last year, and even optimistic official figures say GDP is expected to fall 2 per cent this year. Although Rajoy says his cuts are “to calm the markets,” speculative attacks on Spanish bonds are occurring after major reforms are announced.

As the ratio of public debt to GDP increases, and nervous lenders demand increasingly unsustainable levels of interest (which have doubled since 2007, a full and dramatic bailout is looking inevitable. In short, we are witnessing a slow-motion train wreck, and because the Spanish economy is four times the size of Greece’s, this could have a huge international impact.

Emerging Political Crisis

Economic instability and austerity are also producing political turmoil. Half a year after winning an absolute majority, support for the PP is already eroding and it unexpectedly lost recent regional elections in Andalusia. Renewed tension between the central state and Spain’s historic nations and regions is emerging as the government moves to directly intervene to control devolved budgets.

Most encouragingly, within a hundred days of being in office the government faced a powerful general strike against the labour reforms. The highly-distrusted PSOE maintains historically low ratings despite a sharp turn to mobilizing against austerity and the more left-wing United Left, based on the former Communist Party, has made significant but limited advances.

Voting intentions only partially reflect growing anger in Spain. A better expression was when the king of Spain was caught (after an accident) spending tens of thousands of euros of taxpayers’ money on shooting elephants in Botswana after giving a speech defending the need for austerity. Such was the anger against this hypocrisy that even moderate political leaders suggested the previously popular monarch should abdicate. The way this fed into a wider crisis at the time was described by the El Pais columnist Josep Ramoneda:

“As if Marx were right, chaos in the economic infrastructure is causing growing disorder in the political superstructure.

“Thus we are seeing…a generalized crisis in political distrust … [regional autonomy] being seen as exhausted; a deep moral and cultural crisis; an institutional crisis at the highest level – affecting the head of state – and a diplomatic crisis with Argentina [after the latter nationalized the Spanish Repsol oil company] that has shown Spain’s limited weight in the world.”

His description offers more than a whiff of periods from earlier periods of Spanish history that were riven by deep conflicts (such as in the early 20th century when Spain lost its last colonies, regional-national conflicts emerged and a republic was formed). As economic turmoil continues, such malaise could strengthen and feed into social struggles.

A Year of the 15 May Movement

Social struggles have been a feature of the intensifying austerity. The key turning point was the inspiring explosion of the 15 May movement of the indignados last year. This emerged in response to the deterioration in job and other prospects for young people (52 per cent of whom are currently unemployed) and as a rejection of the ‘political class.’ It was also shaped by disaffection toward the major unions which, despite holding a general strike the previous September, had since backed the drastic pension cuts. As a result the 15 May movement burst out away from traditional union and left-party channels.

The 15 May movement has preserved its capacity to mobilize, holding two days of protest – 15 October and 12 May this year – in which many hundreds of thousands demonstrated in 70 cities. During the protest last month mass assemblies were once again held in city squares and people camped until the movement’s anniversary on the 15th. Then a multitude of ‘blockades’ and other actions were held against the banks and the PP.

Compared to last May, there has been a fall in the number of activists involved and the effervescent climate has resided. Nonetheless, a wide network of activist centres that did not exist prior to last year has been maintained, and public sympathy for the movement remains high (at 68 per cent according to a recent poll).

Rise of Autonomism

One of the key political tendencies dominating the form and content of the new movement is autonomism. Put crudely this is a mixture of anarchism and Marxism whose strategy centres on radical struggle and organizing separately from ‘power structures’ – normally seen as including traditional workers’ organizations. Its strong influence has not been because most activists are consciously ‘autonomist’ but rather because the ideas of this movement seem ‘common sense’ to those who want to fight to gain greater control over their lives but who lack political experience (or union membership – as is the case with large numbers of young people in insecure employment).

Autonomism has had a positive influence on the movement – for instance helping centre its political practice on extra-parliamentary struggle and direct democracy. However, in many ways its politics have slowed the movement’s development. After the PSOE and PP reformed the constitution, the bulk of the movement refused to join the major unions on demonstrations, so limiting opposition to this historic attack (a refusal not reciprocated by the unions who have called on their members to join indignados protests).

This division contrasted with the joint struggles between the indignados and the PAH anti-eviction platform which have successfully defended hundreds of families and encouraged a process of legal reform.

Also the original autonomist insistence on creating maximum demands in ‘de-centralized free spaces’ has proved self-limiting. Increasingly repressive police violence against occupations has shown that reclaiming space can only be temporary under capitalism, and spreading the movement wider has been hampered by not prioritising concrete demands or coordinating centrally.

However, there have been big debates in the movement over these issues and over the last year the movement has matured in the face of many political trials. It is now clear that the status quo can survive occupied squares, creating a debate about which geographical spaces and ‘social subjects’ have the potential to transform society (we socialists argue it is workers in offices and factories).

There is also greater willingness to make concrete demands, with the 12 May protest being based on just five. Likewise the mood to avoid politics in the struggle has also waned, as shown in the proposal to counter the Friday reforms with protests outside the PP headquarters. The anti-capitalist left is now allowed to participate openly in the movement. Whereas the Madrid camp protests last year were dominated by demands for electoral reform, this time they were about cuts and the debt.

Role of Unions

Particularly encouraging is the growing convergence between the 15 May network and organized workers. Despite continued sectarianism toward the large CCOO and UGT unions, there have been alliances between activists and trade unionists defending hospitals and education. One of the most visible groups in the new occupations were teachers in their trademark coloured T-shirts.

The 15 May movement has been a factor in revitalising workers’ struggles (alongside the savagery of the cuts). The 29 March general strike was particularly big and in addition on the day a million demonstrated and large numbers of young people joined radical pickets. There are other advances in labour militancy linked to the movement.

Last September teachers in the Madrid region organized intensive strikes through 15 May-type assemblies (although the protests were part-scuppered by union leaders). At the time of writing primary, secondary and higher-education teachers (and students) are set to strike across the peninsula. In Valencia, where large demonstrations were held after teenage student protesters were brutally attacked by riot police, six strike days in education are planned. Union activists believe the UGT and CCOO may call another general strike in the following months.

With a rising tide of class struggle and politicization – inspired by the radicalizing example of the 15 May movement – and a progressively brutal and pressurized ruling class, the stage seems set for bigger confrontations.

As each neoliberal reform further fans the flames, while squeezing the economy ever downwards, it is not impossible to imagine Spain becoming another ‘Greece’ (although the left and the unions are weaker in Spain). The small and fragmented forces of the radical left need to rise to the challenge ahead and build new alliances for the coming period. •

This article first appeared at socialistreview.org.uk.