Stories about Canada’s role in the world define “who Canadians are” and “who they are not.” The story that gets told most is a positive one. Canada, benign and benevolent, promotes free markets, democracy and multiculturalism while protecting peace, stability and human rights in each country it engages in or does business with. Optimistic and confident, this glowing story about Canada in the world is packaged and sold, over and over again, year after year. It shows up in the speeches of Prime Ministers and in the press releases spun by the major parties; it circulates across the news media and in popular cultural forms; it carries daily conversations.

Nonetheless, the story of Canada abroad may get Canadians to think and feel themselves to be “global” subjects even when many are “local.” Unlike diplomats and CEOs, most people cannot afford to be footloose. Bound to place by waged work, many Canadians do not have the money, time or privilege to “de-territorialize.”However, this story of Canada the do-gooder abroad often deflects attention away from real social problems at home. Hard to consume social facts – class inequality, poverty and homelessness, racist and sexist oppression, the legacy of settler colonialism, and the rise of white Right extremism – are minimized if not denied in the story we tell about our “way of life” around the world. In a time when the Canadian State tries to sell a soft power-maximizing brand image of Canada to the world, the antagonistic bits and pieces of Canada’s history and present get buried.

Furthermore, the story of Canada in the world makes it seem as though all Canadians make foreign policy decisions. Yet, only a few Canadians have the power to decide what Canada actually does in the world and why. For the most part, Canada’s most consequential global actions are not shaped by all, but by a few Canadian business elites and their ministerial boosters at Global Affairs and National Defence.

In this regard, the story of Canada in the world is often little more than PR for those who run Canada’s multi-national corporations and administer the Canadian State’s geopolitical strategy on their behalf. This is not a national story written by all Canadians, but one crafted by Canadian elites. It is a story that masks Canada’s conflicts at home and distracts Canadians from the violence done in their name abroad.

For those seeking a class conscious and genuinely internationalist alternative to the reigning story about Canada in the world, Tyler Shipley’s new book, Ottawa and Empire: Canada and the Military Coup in Honduras (Between the Lines, 2017) is a must read.

According to Shipley, Canada is a “secondary imperial power” whose global incursions and ventures work to secure the ideology of neoliberalism and the profits of big corporations in a world capitalist system already rigged in their favour.

Far from having virtuous effects, Canada’s diplomatic emissaries and Bay-street backed industrial giants have tacitly and explicitly dispossessed indigenous peoples of lands, resources, and cultures, destabilized democracies, and thwarted human rights.

Shipley’s book centers on the Canadian State’s support for the 2009 military coup d’état of Honduras’s democratically elected and popular president, Manuel Zelaya, and interrogates how the Canadian State propped up an oligarchy-friendly dictatorship hospitable to Canadian capital. [Ed.: for more on the coup, see Bullet No. 231, 234, 238, 290.] Taking this specific case to be “paradigmatic” of the new Canadian imperialism, Shipley’s accessible and lucidly written book debunks “several of the cherished myths that Canadians are taught about their country” (p. 3). It makes a timely and valuable contribution to contemporary political economy and critical cultural studies research about Canada’s real role in the world.

Todd Gordon’s Imperialist Canada, Jerome Klassen and Greg Albo’s edited collection, Empire’s Ally: Canada and the War in Afghanistan, Jerome Klassen’s Joining Empire: The Political Economy of the New Canadian Foreign Policy, Paul Kellog’s Escape from the Staples Trap: Canadian Political Economy After Left Nationalism, and Todd Gordon and Jeffrey R. Webber’s devastating Blood of Extraction: Canadian Imperialism in Latin America are keyworks in 21st century studies of Canadian imperialism.

Shipley’s book is a great addition to this field as well as to historical materialist international relations.

Bringing Canadian foreign policy down to earth from the heights of liberal idealism and up from Left nationalist defensiveness, Shipley’s book deters readers from seeing Canada as an anti-American hero or as a pathetic periphery of the U.S. Empire. It gives evidential weight to the argument that Canada is an imperial power in its own right.

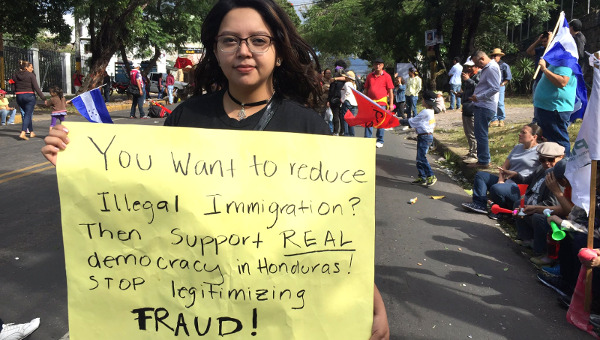

Moreover, Shipley’s book disassembles the nuts and bolts of Canada’s imperial machinery and demolishes the hubris of Canadian foreign policy spin. It introduces readers to the movements of the Honduran people struggling against homegrown oligarchs and militarists and foreign-owned mining, garment and tourist companies.

Significantly, Shipley’s book pushes for international solidarity between Canadian and Honduran social movements and presses for global solidarity among all who are struggling for a world without imperialism, neoliberalism and militarism.

Crucial to building global solidarity is the re-energizing of a heterogeneous and democratic socialist movement in Canada that is capable of replacing the ruling class’s story of Canada in the world with one that supports cultural dignity, social justice and peace for all. •