Should the Left and labour support a demand for a Basic Income (BI)? This simple question has provoked a fervent and confusing debate. The discussion over BI touches on real political and economic anxieties. The attack on the social welfare state, the depreciating power of organized labour and an economy producing increasingly low-wage precarious jobs have led many to search for alternative mechanisms and policies to address these problems. It is no wonder that BI with its promise of streamlined access to minimal economic security has attracted many adherents on the Left.

Discussing BI with clarity is made difficult because of the sweeping scope and abstractness of the issue. Debates over BI necessarily involve an analysis of capitalism, the state, the nature of automation and theories of social change.

Discussing BI with clarity is made difficult because of the sweeping scope and abstractness of the issue. Debates over BI necessarily involve an analysis of capitalism, the state, the nature of automation and theories of social change.

Another added difficulty in debating BI is that the policy has many different variants. Proponents of BI have been able to deflect criticism by creating a division between good BI and bad BI. Instead of a concrete debate about the economic and political aspects of BI, it is discussed as an ideal separated from the messy business of material reality. The strategy of those advocating BI centres on crafting policies in a vacuum and hoping governments enact them.

This romantic idealism has stymied serious analysis of the policy from the Left. Taking a step back and looking at the economic and political logic of BI, I hope to show that however well-meaning the policy is, it is economically flawed and a politically dangerous demand for the Left to adopt.

Costing BI

The three major forms of BI are: targeted, universal (UBI), and negative income tax. All of these have numerous permutations in regards to coverage, relation to other programs and the designated amount of money going to individuals. The targeted form, which is what is being rolled out in Finland and being proposed in Ontario looks to give designated low-income earners a single monthly cheque instead of them accessing social welfare provisions. UBI aims to give everyone a single monthly cheque regardless of their income. The negative income tax model essentially ensures everyone under a designated income amount is raised to that through a dispersal of cheques.

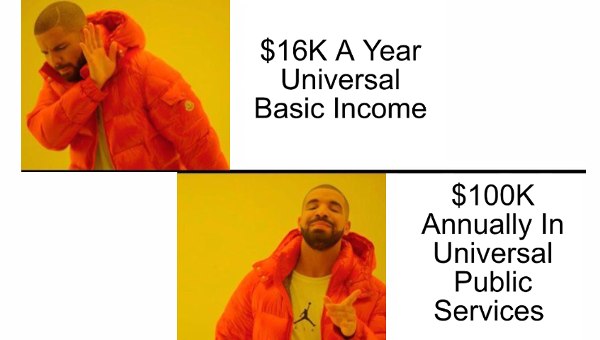

The first question we should ask is, what are the basic costs of these models? Looking at Ontario, Michal Rozworski has pointed out the cost of the universal model, even when set at a low rate, is exorbitant.

“Giving every Ontarian even $15,000 annually would cost $207-billion, just over 25% of provincial GDP. Even limiting basic income to everyone over 15 years old would still come out to $172.5-billion. Increase the basic income amount and the cost rises in tandem. Even a $10,000 per person annual basic income would cost a bit more than what Ontario currently spends on everything else put together.

“To implement a $15,000 basic income, while getting rid of welfare, but keeping things like education, healthcare and higher education, would still mean raising an additional $200-billion in revenues. That’s more than double the $91-billion Ontario is able to raise in taxes today.”

Universal coverage, set at extremely low rates, even if other social welfare provisions are cut, still requires the raising of massive tax revenues. David MacDonald of the CCPA notes that even to universally distribute just a $1,000 cheque to Canadians per year, without cutting any social programs, would mean raising $29.2-billion a year in new revenue (roughly equivalent to 14 per cent of existing federal revenues), even after accounting for claw backs and tax backs of revenue. MacDonald notes this would achieve at best less than a 2 per cent reduction in the poverty rate in Canada, which he says would “be quite wasteful” when considering the amount of money spent.

The negative income tax model, which essentially is a targeted transfer of wealth to the poor, would also be highly expensive. To set the negative income line at $21,000 (if you are earning below that amount you would receive a cheque to boost you to that level), would require somewhere between $49-billion to $177-billion in new revenue depending on how many other social programs were left in place. But what if other social programs were cut, wouldn’t this allow rates to be set higher?

The CCPA study, “The Policy Makers Guide to Basic Income,” answers that question conclusively, “broadly speaking, cancelling existing income transfer programs in favour of a single basic income results either in dramatically higher levels of poverty, or ethically and politically unsupportable compromises where seniors are pushed into poverty to lift up adults and children.”

The targeted model is more cost efficient, but the very nature of targeting small populations through means testing is little different than what already exists. More money in the hands of people who need social assistance, with less red tape, is undoubtedly a good thing. But the targeted BI model and small-scale experiments really do not make the case for wider adoption. There is no reason to think this is more efficient or politically possible than strengthening existing social programs.

The BI and the Logic of Capitalism

The goals for a left-wing version of BI are to eradicate or minimize poverty, to ensure consumer demand, redress inequality and to empower workers by providing a guaranteed minimum level of income for all citizens. The idea is to create a social policy, which allows workers to have the financial means to meet their basic needs without necessarily accessing the labour market. This would give workers more power and confidence to demand better pay and working conditions from employers. BI would ultimately give workers alternatives and autonomy, while also ensuring those, who for whatever reason are unable to work, can access the material means for a decent life.

Outside of the very real costing problem, the logic of BI falls short. Capitalism operates on the extraction of surplus labour from workers. Workers sell their potential to work on the labour market and employers put them to work, paying them a wage that is less than the value they produce with their labour. This surplus labour is ultimately the source of profits. Capitalism needs workers. Much of the history of capitalism centres around the creation of a working class that is more or less reliant on selling its labour power for a wage in order to live.

If workers in large enough numbers are able to sit outside of the labour market and sustain their basic needs, capitalism would cease to function. BI naively assumes that capitalists and the state would not respond politically and economically to the changing market condition of labour. The logic of capitalism would push capitalists to, at the very least, raise wages and increase prices on goods and services. The ultimate goal would be to compel workers back into the labour market, and make them dependent on selling their labour power in order to live. As Thom Workman and Geoffrey McCormack note:

“The fact that workers – even those who are fond of their jobs – sell their labour power to employers out of necessity is the bottom-line reality that must be preserved through social policy. The cultivation of genuine alternatives for working people, perhaps in the form of alternative communities tied to the land (history abounds with such experiments) or in the form of legislation guaranteeing annual incomes which permit families to live modestly but with greater dignity, would have the effect of undermining capitalism by undermining its coercive labour supply.”

Those advocating BI want to leave the basic mechanism and relationships of capitalism in place, but alter the dynamics of the labour market. Capitalists would still own business, property and control finance. The idea that capitalists or the state would simply allow workers to achieve BI at a rate that would meaningful alter the balance of class forces or mess with the central coercive function of the wage labour market is a fantasy.

More than simply costing too much, the economic vision of BI is incompatible with the logic of capitalism.

Politics and the State

The major political problem with BI is that it views that state as a neutral apparatus governing relations between workers and employers. The state is, when stripped down to its core essence, a reflection of the interests of the ruling class. The state relies on the smooth functioning of capitalism and its policies aim to achieve this (balancing the competing interests of capitalists and placating any possible rising working class movement). The state, its bureaucracy and the political class, have no real interest in upending capitalist social relations and the basic functioning of the labour market.

The capitalist state is used to push policies that facilitate the continual accumulation of profits by capitalists and foment stability (there are of course differences about how best to do this). A progressive version of BI runs counter to the basic objectives of the state.

Wages and the State

Faced with a period of systemic slow economic growth it is not hard to imagine that the state could adopt a version of BI that aims to subsidize low-wage work. Indeed, in places like the United States this is the defacto situation with Walmart workers surviving only by accessing food stamps. A modest BI, of say $10,000 (which would not be enough to empower workers to stay out of the labour market for long), would essentially be a top-up of wages for low-wage employers. It would be a weapon for employers to keep wages low, as they could argue there is no need to pay workers more because of BI. In this scenario why would employers not just pay the minimum wage if there was a BI top up?

BI as a wage subsidy for employers would have the effect of distancing workers’ labour from their wages. Instead of being paid directly for their work, part of the wage of workers would come from their own tax dollars in the form of BI. Workers are powerful because of their social location in relation to production. But having the state subsidize employers’ wages clouds the relationship between workers, employers and their profits. Instead of pushing against employers in relation to their profits, workers would have to formulate their demands in terms of a social wage. This would have the effect of obscuring class division, exploitation and capitalist social relations in society. A state subsidy of wages could easily disempower workers as a class relative to employers by blunting the class struggle and turning it into a technocratic argument over the level the state should subsidize employers’ wages.

Added to this very real possibility, is likelihood that the state would use BI to attack public sector unions. Workers who staff and administer social programs could easily loose their jobs if services were cut to make way for BI, which is why public sector unions like OPSEU oppose it. Other public sector workers would also face increasing pressure of concessions to wages and benefit as the state would scramble to minimize costs to pay for BI. Governments would likely pit public sector wages and benefits against BI for the public. If BI subsidized low-wage employers this would have the effect of putting added downward pressure on all unionized workers.

Political Struggle and BI

The debate over the social usefulness of BI is largely conducted in the realm of abstraction. Policy is dreamed up, calculated, and debated with next to no appreciation of how the political struggle could and would shape the proposed policy.

By subtracting the political from the equation of BI, its proponents treat the economy as a neutral object that can be simply rearranged. This approach engages in the worst kind of academic idealism that shuns any serious political analysis. As John Clarke notes:

“I’ve yet to see, quite bluntly, any serious attempt to assess what stands in the way of a progressive BI and what can be done to bring it into existence. It simply isn’t enough to explain how just and fair a given model would be if it could be adopted. In order to credibly advance BI as the solution, there are some questions that must be settled.”

As parts of the Left flirt with idyllic visions of BI, the right-wing is busy actually using the renewed interest to push their own political agenda. In Finland, the right-wing government is supporting BI, which is now in its testing phase, as a way to rollback the social welfare state and curb the power of trade unions.

In Ontario, the Liberal government is moving ahead with its BI pilot project. The pilot project would put a select group of low-income people on a BI. The Liberals have been using this idea to delay any meaningful action toward reducing poverty in the province. As Clarke argues:

“If the concept is being advanced in Ontario by the very provincial government that has led the way in program reduction and austerity, it is not because they want to reverse the undermining of income support, the proliferation of precarious employment and the privatizing of public services but for the very opposite reason. They are looking with great interest at the possibility of using Basic Income as a stalking horse for their regressive social agenda and it will be the version that Bay Street has in mind that will win out over notions of progressive redistribution.”

Rather than raising the rates for social assistance, increasing the minimum wage or spending more on social services the government is touting its BI experiment. The Liberal’s advocacy for BI also comes at the same time as the Changing Workplaces Review, a full-scale review of all labour law in the province. By propping up BI the Liberals are looking to stoke confusion and division amongst those pushing for paid sick days, a $15 minimum wage and stronger union rights. The Liberals are not alone in this effort.

In its effort to weaken labour laws, the Ontario Chamber of Commerce has made support for BI one of its key proposals in the Changing Workplace Review. This of course is not some noble gesture, BI in reality dovetails perfectly with its worldview.

BI is not just a left-wing idea, it has also long been advocated for by parts of the right-wing, such as Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek. The goal is to use BI to do away with the social welfare state. Instead of social programs, citizens are given minimum cheques by the state and then purchase their social needs on the market. BI will not be used to decommodify social relations, but used to desocialize state services.

Pushing Paper, Not Moving People

Many of BI’s Left proponents are not just failing to challenge the right-wing versions of the policy, they are getting in bed with them. Rather than treat them as attacks on labour and the social welfare state, they are treating them as tentative first steps toward a better BI. Earlier this year, Guy Standing one of the main academic boosters of the BI, went to the World Economic Forum in Davos Switzerland to sell the idea to the world’s elites. He is also pushing the extreme right-wing Modi government in India to institute UBI. It is no wonder that Tory politicians like Hugh Segal, who is leading Ontario’s Basic Income pilot project, have adopted Standing’s beyond left and right policy frame and analysis.

BI advocates are not aiming to build a social movement around these ideas, rather their goal is to persuade policy makers. The self-activity of workers in the process of achieving BI is at best reduced to voting for the issue during an election. BI is left to experts to calculate and implement. The problem is what is dreamed up in the laboratories of social policy is very far removed from the needs of workers. Instead of trying to create a political pole for the working class by empowering workers, unaccountable BI experts aim to substitute their visions for the voice of workers.

The version of BI that we are likely to get will reflect the balance of class forces. So when BI advocates focus on pushing policy papers rather than moving people it portends trouble. For this reason BI is not some sort of transitional demand which aims to push the envelope of what is possible under capitalism in order to build a working class movement to go further. Its wonkish approach to policy construction and appeal to experts fits seamlessly within the current political structures.

The very same forces that make it difficult to win improvements in current social programs, would not be magically abolished by the implementation of BI. In many ways BI presents more favourable conditions for employers and the government to attack social programs, as it is much easier to shape new social policy, than it is to rollback existing ones.

Beyond Basic Income

The political reality of BI is that the capitalist class will never support a version that will strengthen the hand of workers. All BI proposals imagine a capitalist class that will retain full control over businesses and property in society and not react when vast amounts of resources are given to workers.

Those BI supporters who acknowledge that existing proposals of BI are lackluster or even regressive, hold onto the idea a good BI is still worth fighting for. The problem with the division between real world BI proposals and ideal theories of a positive BI, is that the latter makes the former possible.

A progressive vision of BI speaks to the real desire to address the rise of precarious work, to make welfare less punitive, and to have justice for those who can never be part of the labour market.

We need to understand that BI is neither politically nor economically possible under capitalism. This is not to consign ourselves to defeat and inaction. Burying the idea of BI as a viable strategy to respond to inequalities and injustices of capitalism allows us to focus on strategies that can help us build the power we need to achieve economic justice and dignity for all. •

This article first published on the Hammer Hearts blog.